On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: eight

Tuesday, June 7th, 2016[ by Charles Cameron — omega worms in science and scripture ]

.

As regular readers know, I am interested in Omega — the End, in “alpha and omega” terms — so I was naturally intrigued by this tweet, with Adam Elkus kindly put in my twitter feed and those of others who follow him:

If you are a worm scientist and know what a "omega turn" is, please help fill out our survey! https://t.co/a0JggSHEiH

— OpenWorm (@OpenWorm) June 7, 2016

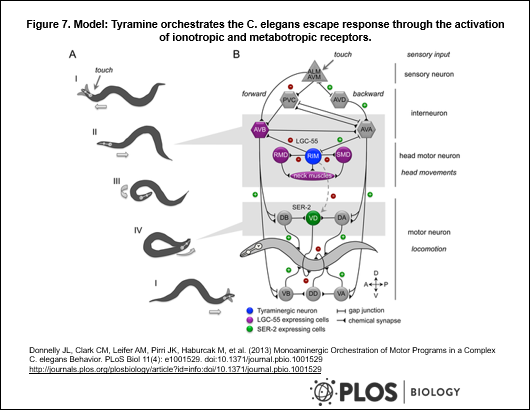

I’m not a “worm scientist” but wanted to know what an omega turn is, so I browsed around a bit and found this diagram:

Donnelly et al, Monoaminergic Orchestration of Motor Programs in a Complex C. elegans Behavior

**

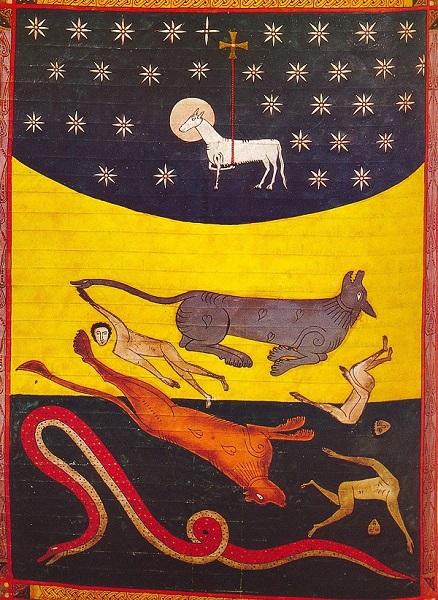

Now please don’t imagine I know what that means to a worm scientist — I was expecting something more like the worm in the lowest section of thIs Beatus Apocalypse:

or maybe this:

from a different Beatus manuscript, where it appears the worm has turned quite a few times.

**

In the unlikely event that I should attempt a translation of St John‘s revelatory vision on the Isle of Patmos into science fiction, be assured that I shall include a reference to that image among my illustrations, with a footnote perhaps, pointing to Mark 9.48:

Where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched.

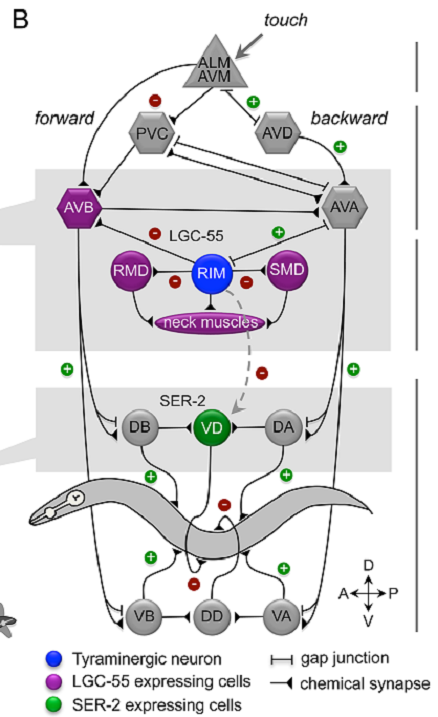

Today, however, my appreciation for all things apocalyptic must give way to another interest of mine, that of the pervasive use of [node and edge] graphs in our contemporary world. Here again is the central column of that image:

It interests me here as yet another illustration of the degree to which graphs serve as a fundamental substrate of our understanding of the world — and hence my continuing interest in their use in game board design — both of which I’ve been exploring in other posts in this series:

On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: preliminaries On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: two dazzlers On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: three On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: four On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: five On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: six On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: seven

**

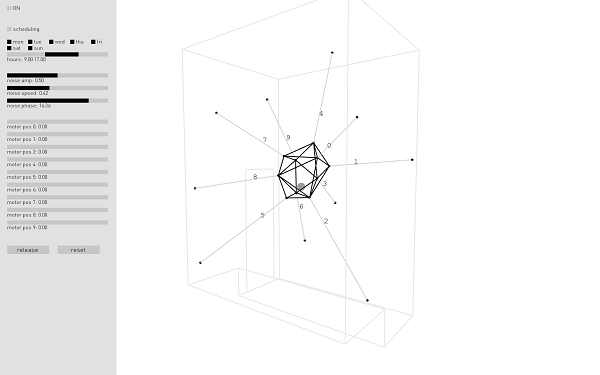

After the glamour of Beatus manuscripts and PLOS worm diagrams, it may seem almost a let down to turn to irregular polyhedra — but the move from two-dimensional graphs to their three-dimensional cousins is a short one, and since we live in what at least appears to be a (spatially) three-dimensional world, one which should also be considered in terms of game board and concept-modelling design.

The following illustration —

— and accompanying video, from Filip Visnjic, Irregular Polyhedron Study #1 – Vertex, edge and volume, may accordingly be of interest:

Irregular Polyhedron Study #1 from Bjørn Gunnar Staal on Vimeo.