Of the sacred, III: saliva redux

[ by Charles Cameron — yet another angle on religious violence ]

.

Religion can be a lot stranger than one might think.

.

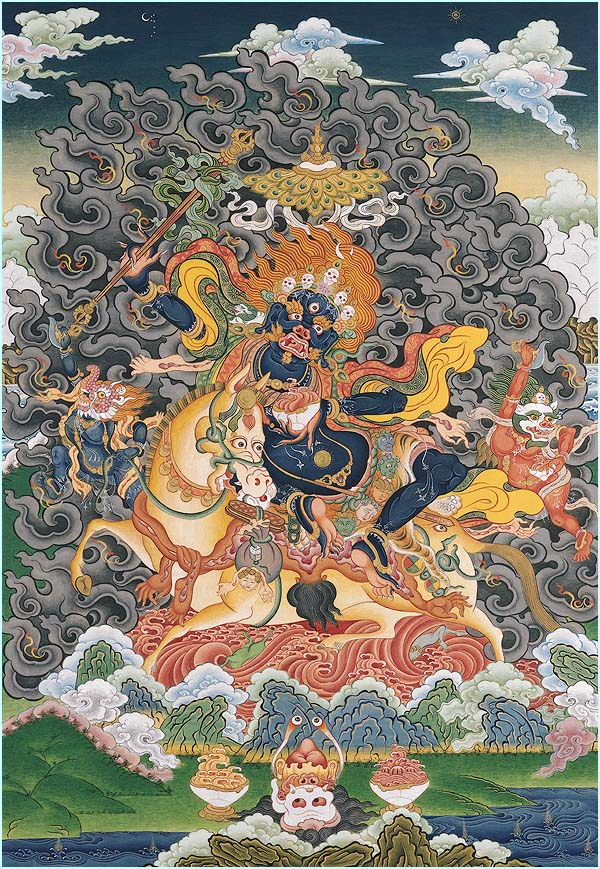

Wrathful deity, Tibet

Here, I’m going to tie in my recent post about Iranian clerics claiming Khamenei‘s saliva could cure diseases with the notions of religious danger and religious violence.

Bear with me, this will give us a richer understanding of how religious violence may work with people who are naturally rule-averse — and I’m thinking here of criminals who get into a mix of religion and violence, including criminals who get involved in jihad, but also the cultic side of cartel violence in Mexico.

My aim is not to explicate either of these phenomena specifically, nor to claim they necessarily resemble each other or the punk or Hindu practices I’ll reference, but simply to suggest again, from another angle, how astonishingly diverse, powerful — and frankly surprising, disgusting and on occasion dangerous — religious expressions can be.

**

In my post about Iranian clerics’ claims of virtue for the Ayatollah’s saliva, I drew on other examples in Islamic, Hindu and Christian traditions where the saliva of saints was considered capable of conferring blessings. Marcus Ranum replied with a hilarious, down to earth comment about Chuck Norris‘ saliva, and Derek Robinson then chimed in with a link to a story about punk rockers and spit:

It was the glorious contemptuousness of spitting, of course, that lay behind its enthusiastic adoption by rock stars and others attempting an instant badge of streetwise chic. Spittle’s finest hour came when the activity was adopted as a collective pastime by fans of punk in the 70s, although, according to Jon Savage, the author of England’s Dreaming, a history of the period, the affection for flob may initially have been accidental. “There are various theories as to how it all started but it seems to have originated, with Johnny Rotten blowing his nose on stage when he had a bronchial problem. He may have started the whole thing, unconsciously.” What probably gave the habit legs, he says, was the penchant of the Damned to go to other bands’ gigs and spit at them from the mosh pit as a sign of disapproval.

“The interesting thing about punk spitting was that it was supposed to be friendly, a gesture of solidarity. It was a clever inversion by the punk audience: if you call us disgusting, we’ll show you that we can be disgusting. Bands at the period routinely complained about having to come offstage because they couldn’t play with their hands slipping all over their guitars, however, and if you look at footage of the period – there is some of the Clash in 77 – they are operating in a hail of spit. Completely disgusting.” The power of sputum in punk reached its zenith when Joe Strummer, the band’s lead singer, caught hepatitis after accidentally catching a blob of goo on stage.

What’s clear from this quote, I think, is that the idea behind all this spitting is what some scholars call “transgressive” — there’s a delight here in going beyond accepted boundaries? — and I think FWIW that that’s very much part of what some tantra is about.

**

So we’re in the realm where excitement is generated by doing what’s against the code — moral, legal, social, whether written or unwritten. There’s a frisson of excitement there, in crossing the line, and in religion the technical term for religious practices that explore the crossing of lines and breaking of taboos is “antinomian”.

There are plenty of examples of antinomian behavior in religion. They often crop up when new religious movements are born in defiance of an existing order perceived as unjust, corrupt or hypocritical — as when some medieval heresies held that stealing from wealthy bishops to share food with the poor was more in line with Christ‘s teaching than paying tithes to support the bishop in his splendor.

Perhaps the most interesting example in Christian history is that of the agapetae or subintroductae, who in the early church made the experiment of sleeping together as couples without sex, as if to demonstrate by deed that their love in Christ (agape) was stronger than the love of sexual desire (eros). As Charles Williams noted, the experiment often failed, and the Church Fathers accordingly shut it down.

It’s instructive, I think, that Mahatma Gandhi attempted the same experiment, inviting his 19-year-old grand-niece Manu to share his bed without sexual relations. As Stanley Wolpert put it in Gandhi’s Passion: The Life and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi (OUP, 2002):

Gandhi was testing the “truth” of his faith in the fire of “experience.” His had always been a practical philosophy, an activist faith. He appears to have hoped that sleeping naked with Manu, without arousing in himself the slightest sexual desire, might help him to douse raging fires of communal hatred in the ocean of India, and so strengthen his body as to allow him to live to 125 in continued service to the world.

I have an extensive set of notes on both the subintroductae and Gandhi’s prayog, prepared as a briefing for a scholar friend’s use in legal proceedings, available on my Forensic Theology blog for further reading. Here, I’d simply note that the breaking of codes and taboos regarding purity, cleanliness and sexuality forms part of the approach to spiritual liberation known as tantra, in which all the energies of human desire, including those normally repressed, may be brought into play under focused, conscious spiritual direction, in the effort to achieve transcendance.

**

Some Tantric practices are not transgressive of any boundaries — forms of meditation focusing on the energy of breath (pranayama) within the seated body, for instance. But some are, as we can see from Loriliai Biernacki‘s book, Renowned Goddess of Desire: Women, Sex, and Speech in Tantra (Oxford UP):

What do we mean when we talk about the “transgressive” in Tantra? The idea of the transgressive gets neatly encapsulated within the Tantric tradition in a simple and pervasive list of words all beginning with the letter m. The “Five Ms,” a list of five substances, including, for instance, liquor and sex, become incorporated within ritual worship of the goddess. The five elements are meat (mamsa), fish (matsya), alcohol (madya), parched grain (mudra), and illicit sexual relations (maithunam). The transgressive ritual that incorporates these substances is designated as “left-handed,” following a nomenclature also prevalent in the West where the right hand is the auspicious and normatively socially acceptable hand and the left represents that which must be repressed and expelled.

The “Five Ms” have elicited a concatenation of emotional Western and Indian appraisals of Tantra ranging from a Victorian repulsion and embarrassed dismissal to ecstatic embrace by contemporary popular culture in the West.

Another aspect of the same tantric strategy consists in arousing and transmuting the energies of disgust by meditating in charnel grounds — the location favored by Lord Siva himself. Mark Taylor has a fascinating and thought-provoking commentary on the cross-cultural role of bones, skulls and skeletons in religious practice in his Cabinet article, Sacred Bones.

**

Now let’s get back to the our starting point: saliva.

Alf Hiltebeitel in his book Criminal Gods and Demon Devotees: Essays on the Guardians of Popular Hinduism (SUNY Press) describes how the god Shiva (Siva) pulled a devotee of his who was a hunter “completely out of the web of conventions that make up the communal life of hunters”. I think you can get the gist even if you don’t know all the technical terms in these paragraphs, but “apna” is love or devotion, and a “linga” is the god Shiva worshiped in the form of a symbolic, stone penis, and the Agamas are scriptures:

When Tinnanar decided to clean his Lord up and to feed him, he did so in complete ignorance of the Agamas and acted as an infatuated Untouchable hunter would. He brought to the linga pig’s meat that he chewed in order to find the tastiest morsels, water that he carried in his mouth, and flowers that he stuck in his hair. He then performed puja in ways that the Agamas rank as defiling. He brushed the linga off with the sandal on his foot, he bathed it by spitting water over it, he dropped the flowers from his head onto Siva’s, and he fed him the saliva-drenched pork. He did this for six days.

In the meantime, Kalattiyappa explained to a Brahman who served the linga while Tinnanar was away hunting why he enjoyed Tinnanar’s abominable ritual, a lengthy explanation summed up by one example: “The water The water that he spits on us from his mouth, because it flows from the vessel made of love called his body, is more pure to us than even the Ganges and all auspicious tlrthas. Anpu is the normal experience we have when our feeling, thinking, and speaking are unified in an attentiveness to another that we call infatuation, but infatuation for Siva may carry one far beyond normal moral boundaries.

**

Humans come in all shapes and sizes, qualities and kinds — and it appears that at least in this Indian example, the divine is prepared to bless the human “where the human is at” — in a manner according with his own nature.

If we can understand this, perhaps we can understand also the curious paradox by which the book Wild at Heart by the Colorado Springs evangelist John Eldredge, becomes part of the “Bible” of La Familia, the Mexican narco-terror group, how the deceased Mexican bandit, now a folk-saint, Jesus Malverde, receives prayers like “Lord Malverde, give your voluntary help to my people in the name of God. Defend me from justice and the jails of those powerful ones” — and how more generally, terror groups with a strong religious ideology can easily number petty criminals and the like among their enthusiastic members, without ceasing to draw on religious motivation.

*****

ADDENDUM regarding the illustration at the top of this post:

A wrathful deity is characteristically wrathful in the sense of Malachi 3.2:

And who can stand when He appears? For He is like a refiner’s fire…

Speaking generally, the purpose of the wrath is purification. It may be helpful to bear this in mind as you contemplate the full image of that wrathful Tibetan deity which heads this post:

Full image of Tibetan wrathful deity seen above