Knowledge Expertise as a Springboard instead of a Cage

Steve DeAngelis had an excellent and timely post on the cognitive diversity involved in the creative process of innovation, working off an  article in The New York Times, Innovative Minds Don’t Think Alike:

article in The New York Times, Innovative Minds Don’t Think Alike:

“There is a lot of denial when it comes to the curse of knowledge. Nobody likes to admit that they are incapable of thinking out of the box. Entrepreneurs pride themselves on being able to envision the “next big thing.” Designers and inventors are always looking for better ways to do things. The good ones have learned tricks that help them break down the walls of knowledge. According to Rae-Dupree psychologists have conducted experiments that demonstrate that a person’s first instinct is to think about old things rather than new things. That’s not really surprising since we can only think about what we know.

‘Elizabeth Newton, a psychologist, conducted an experiment on the curse of knowledge while working on her doctorate at Stanford in 1990. She gave one set of people, called ‘tappers,’ a list of commonly known songs from which to choose. Their task was to rap their knuckles on a tabletop to the rhythm of the chosen tune as they thought about it in their heads. A second set of people, called ‘listeners,’ were asked to name the songs. Before the experiment began, the tappers were asked how often they believed that the listeners would name the songs correctly. On average, tappers expected listeners to get it right about half the time. In the end, however, listeners guessed only 3 of 120 songs tapped out, or 2.5 percent. The tappers were astounded. The song was so clear in their minds; how could the listeners not ‘hear’ it in their taps?’

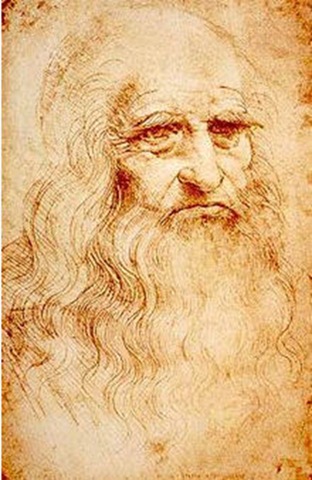

….Rae-Dupree notes that there are ways to “exorcise the curse.” I have written about one of those ways before. Frans Johansson calls it “The Medici Effect” in his book of the same name. He argues in favor of creating a space in which people from diverse fields of expertise can get together to exchange ideas. The Medici’s, of course, were a wealthy and powerful Italian family who played an important role in the Renaissance. The family’s wealth permitted it to support artists, philosophers, theologians, and scientists, whose combined intellect helped burst the historical pall known as the Dark Ages. Getting people with different knowledge bases together means that none of them can remain within the walls of their own knowledge domain for long. As a result, good ideas normally emerge”

Read the rest here.

Acquiring disciplinary expertise typically takes approximately a minimum of 7-10 years for the student to master enough depth of knowledge and requisite skill-sets to become an expert practitioner. In many fields, notably pure mathematics, theoretical physics and  musical composition, this period of early mastery is often the most fruitful in terms of significant contributions of new discoveries or the kinds of innovations that Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Howard Gardner consider to be “Big C” creativity. Einstein’s papers on Relativity or Newton’s early exposition of the Laws of Motion being the great historical examples of paradigm-shifting innovators. If a practitioner remains entirely in that field for their career, cultivating an ever greater and rarefied depth of knowledge ( and thus having fewer true peers and more disciples) further contributions are likely to be of the “tweaking” and “critiquing” variety. Useful but not nearly as satisfying as the grand “breakthrough” moment.

musical composition, this period of early mastery is often the most fruitful in terms of significant contributions of new discoveries or the kinds of innovations that Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Howard Gardner consider to be “Big C” creativity. Einstein’s papers on Relativity or Newton’s early exposition of the Laws of Motion being the great historical examples of paradigm-shifting innovators. If a practitioner remains entirely in that field for their career, cultivating an ever greater and rarefied depth of knowledge ( and thus having fewer true peers and more disciples) further contributions are likely to be of the “tweaking” and “critiquing” variety. Useful but not nearly as satisfying as the grand “breakthrough” moment.

I suspect that the reason for this decline in major creativity has to do with two realities of expertise:

First, the analytical-reductionist emphasis on vertical thinking; cognitively, for an acknowledged expert, there is a great deal more time spent on mere data retrieval, interpretation within accepted frames and scanning patterns for consistency than there is original problem solving, questioning premises, speculating, imaginative brainstorming, analyzing anomalies and thinking analogically. The latter are too often the tools of the novice, the student, the child, the layman trying to grasp in the process of learning what they do not yet fully understand. Too often these powerful ( though tiring and time consuming) cognitive skills are set aside in favor of operating on “autopilot” once the student has achieved mastery. Unless consciously practiced, the hard thinking tends to stop when one is constantly confronted by the routine.

Secondly, disciplinary fields, like all forms of collective human endeavor generate their own cultures with accepted norms, rituals, in-group terminology, orthodoxies, implicit and explicit rule-sets, authoritative hierarchies, politics, and peer presssures. As one gains seniority it becomes harder and harder to rock the boat because challenging one’s peers brings professional risk, social ostracism and conflict while validating the community’s beliefs yields rewards, advancement and praise. A phenomenon of human nature that has been observed by thinkers as disparate as Thorstein Veblen, Thomas Kuhn and Howard Bloom. Vested interests are irrational in their own defense. It is here that knowledge can be come a “curse” and expertise a form of incompetency or blindness to the larger picture ( “educated incapacity” in Herman Kahn’s terminology).

The answer to this problem requires actively determining how we will think about our knowledge. Steve pointed to cultivating “the Medici Effect” of multidisciplinary interaction in his post, a highly effective practice for organizations who want a work force rich in “intellectual catalysts”. To this, I would add another important set of variables: freedom and time. Seemingly non-productive activities, when we are “fooling around” appear to permit an indirect processing of information that leads to a burst of insight about the problem we have failed to consciously solve ( the “idea came to me in the shower” effect). Time needs to be set aside to explore possibilities with acceptance that not all on them are going to pan out ( Frans Johnansson covers these points at length in The Medici Effect). Permitting employees autonomy strikes at the power and culture of American middle-level management, which is why inculcating such practices often founder, even when introduced support of organizational leaders ( “leadership” and “management” are entirely different outlooks) due to the passive or active resistance of those whose position or status in the organization depends upon exercising control.

On the individual level, novelty is an important stimulus toward horizontal thinking. New concepts and experiences stoke our curiousity and “wake” our brains out of the usual, habitual, patterns in which we operate. Attention levels increase as we begin to operate at the beginning of the learning curve and start to recognize parallels and connections between old and new knowledge. We can also make deliberate choices to think “outside the box’ by voluntarily changing our position, perspective and scale, reversing our premises, engaging in counterfactual thought experiments and other lateral thinking exercises. In this way, we are more likely to be behaving metacognitively, aware of both our own thinking and more alert to the nature of the information that we are receiving.

We have something of a paradoxical situation. An untrained mind, looking at a field with “new eyes” is the one most likely to notice that which has eluded the expert of great experience but is least able to make use of, or even assess critically, the importance of their insights. A trained, disciplinary, mind has the capacity to extrapolate/interpolate, practically apply new insights or think consiliently with great effect but is the mind least likely to have any insights that could conflict with the major tenets of their disciplinary worldview.

Having the best of both worlds means avoiding either-or choices in cognition in favor of both. Analytical-reductionism and Synthesis-consilience have to be regarded by serious thinkers as tools of equal value. Imagination and vision should be as important to the genetic microbiologist or physical chemist as it is to the artist but they should be regarded as a complement to the scientific method and logical, critical, analysis, not as a substitute. Looking for alternative choices to a course of action should be valued as highly as correctly identifying the likeliest outcome of the action. We can embrace intellectual curiousity and shun “paralysis by analysis”.

Crossposted at Chicago Boyz.

January 6th, 2008 at 3:58 am

Mark,

This is a great companion piece to the post by Steve DeAngelis!

If I lived within a hundred miles of you, I’d be knocking on your door tonight to buy you dinner and cocktails for such a supurb essay.

I found Steve’s post so stimulating that I was preparing to write about it on my blog. Now with your permission I am going write about both of your posts and send as many readers as I can, your way.

I agree with your twin causes of the decline in creativity. In a side note, I read recently that Paul McCartney and Bill Gates have not had any significant creative achievements since they left their thirties. It had been speculated that they biologically peaked in their early years and became vertical in their thinking due to becoming acknowledged leaders in their fields.

I find that my own experience of becoming a historian after forty years of lifetime experiences seem to have given me a natural inclination to horizontal thinking.

January 6th, 2008 at 1:08 pm

Well said. This seems very close to the deliberation-without-attention effect.

Dijksterhuis, A., Bos M.W., Nordgren, L.F., & von Baaren, R.B. (2006). On making the right choice: The deliberation-without-attention effect. Science, 311, 1005-7.

January 6th, 2008 at 3:58 pm

Hi HG99,

Much thanks! No permission is ever required – link away!

Back when I was in grad school, a while ago, we had a few older gentlemen who had decided to use their retirement to learn about things they were genuinely interested in exploring – one was finishing his PhD in history his seventies, the other starting his MA in his early sixties. Both men made fascinating contributions and enriched the department by being able to bring life experiences to bear on abstract discussions that grad students typically lack.

I wonder how much of McCartney’s problem would be the lack of near-peers with whom to work. Few rock/modern artists have been as prolific at songwriting ( perhaps Ray Charles, Elton John, James Taylor and a handful of others) but it helps to have ppl to bounce ideas off of who can give critical feedback or tweak or make their own original contributions. I’m no expert on the tunes though ;o)

January 6th, 2008 at 4:01 pm

Hi Dan,

I always relish it when you can support my "data-free analysis" with some actual, peer-review, data. LOL!!!!

January 6th, 2008 at 10:51 pm

Which throws an interesting light on the concept of a shared orientation a’ la Boyd. If intellectual diversity is the source of creative thinking/new insight then how do we encourage such creativity within hierarchical institutions whilst maintaining a shared orientation?

January 7th, 2008 at 4:14 am

[…] Article on Knowledge zenpundit.com » Blog Archive » Knowledge Expertise as a Springboard instead of a Cage […]

January 7th, 2008 at 5:34 am

HistoryGuy99’s post is what brought me here and to Steve’s original post. Excellent work gentlemen! You’ve recommended The Medici Effect in the past and this further exploration has convinced me to push it up on the "to read" schedule! This discussion reminds me of Barnett’s work with Cantor Fitzgerald where they brought in "experts" from various areas of study to generate new ideas. Getting the military to think about world markets is progress!

Rather than "knowledge" being the curse, do you think that "success" is also the curse? When you haven’t had that big hit yet, you’ll try anything and everything to discover it. But once you nail it and are rewarded, the fear of not being "that guy that innovated such and such" creeps in. It’s become your identity and it has done well for you. At that point, you’re not that hungry anymore. Now, you also have a lot more to lose. And the perceived loss of status wouldn’t be just from professional peers. It could also be from family and community.

Being from Detroit, I know of many examples in the auto industry. For example, J Mays, current Ford design VP became famous for doing "Retrofuturistic Design" when he styled the VW "New Beetle". That car was a huge hit internationally and rocketed his career at a young age. Since then, that seems to be the only route he’ll take. For example, he was involved in the "new" Ford Mustang, Ford Thunderbird, Ford GT, Ford ’49 and Jag F-type. Each one of them being rehashes of 50’s – 60’s cars. To his credit though, instead of sending his new hires to auto shows to study, among other things, he sends them to study architecture and furniture design in Europe.

Brad B. – Potbangers Inc.

ps, you have the coolest text editor of any blog I’ve visited! I’ve

neverused strikes, but it’s good to know that I can! 😉January 8th, 2008 at 1:35 am

Hi Brad,

You raise a good point about "success" ( which is, of course, in the eye of the beholder) -as long as the person values their "success", whether it is publishing peer review articles or raking in stock options or making partner or winning "custodian of the year" – risk can be inhibited. Good economic thinking on your part.

The text editor is one of the wordpress plug ins – "Tiny something…" LOL! but it’s there in the plug in menu if you are using wordpress with your own domain/template. It isn’t perfect – Mrs. Z hasn’t been able to get the paragraph drop to work correctly – but the trasde off is linking/editing is easier for the commenters.

January 9th, 2008 at 5:14 pm

Hi Mark: — I wrote this originally for Stephen DeAngelis’ blog, but found there were no comments there.

I’d like to propose that the reason, as you say, that "a space in which people from diverse fields of expertise can get together to exchange ideas" is so powerful isn’t because the more "people" the merrier — its because the more "diverse fields" the merrier.

Each new expert, if expert in one field, brings one new family of "frames" together, and it is the viewing of the known facts (and occasional anomalies) in new frames that provides the unexpected glimpses. So that in fact the most useful expertise would be in (almost content free) frames — in knowing a wide variety of angles from which to look at each situation.

But I’d like to take this farther, and then deeper.

I’m speaking of frames, but those are fairly easily gathered by a decent collector, since they don’t on the whole challenge people’s existing emotions — the assumptions which exemplify our worldviews, to which we tend to be emotionally attached, are harder to get at — and deeper still there the archetypes in which our entire sense of reality is anchored, shifts in which, like psychedelic drug experiences, shake us to the foundations.

For a practical minded child of the enlightenment to question some position proposed by John Cain or Hillary Clinton is not too difficult. To admit one’s own foolishness after offering unwanted though well-intentioned advice to a confirmed alcoholic is harder. But to question the law of cause and effect as commonly understood seems, well, suicidal.

And yet that’s what, for instance, al-Ghazali did, and the Islamic world is still halfway of the opinion that he is right. As an author under the pseudonym Spengler put it in a recent article for Asia Times:

That’s a hard one for us to swallow, as is the neo-Platonist view — popular with Marcilio Ficino, the leading light of the Platonic Academy in Medici Florence — expressed here by Plotinus, (and echoed by Shakespeare in a familiar phrase):

These views — that all the world’s a play, that each sparrow falling, each arrow or bullet fired, each airplane tilted towards a distant tower is held between the fingers of a God — they seem unnatural to us, they are foreign, medieval we c all them, archaic even — and yet the hold some terrible compulsion for us, they are the stuff of dreams, and for those whose "niveau mentale" is less firmly fixed in the twenty-first century and its certainties, they can unleash a fervor we find it hard to understand.

My point in quoting al-Ghazali and Plotinus is to show, as Erich Auerbach showed in his Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, that realities at odds with what seems like reality to us have significant histories and can inspire powerful emotions and impassioned acts that leave our western speculative imaginations standing in their dust.

The warfare of the Aztecs, the berserkers seeking Valhalla, and most significantly today, the Islamists seeking martyrdom — these are not "rational actors" in a sense that tweaking our Prisoners Dilemma tables will not address.

To know them, we must think not merely our of the box but out of boxes, take not just the road less traveled but a path so overgrown a machete is required to cut it, and no one can say whether it was a path before, or is new found land, a haunt of owls or badgers, or an habitation of ghosts… a trackless track as zen might call it, crossing the Cartesian rift between brain and mind, passing between real and imaginal, fact and myth, story and history as easily as we might pass between Colorado and Wyoming.

All this requires a sort of intellectual courage … and a poetic / archaic cast of mind.

*

Well, that’s one end of an Ariadne’s thread…

I hope to follow the thread deeper into the labyrinth in upcoming posts.

January 15th, 2008 at 8:04 pm

Stephen DeAngelis continues the conversation:

http://enterpriseresilienceblog.typepad.com/enterprise_resilience_man/2008/01/more-on-the-cur.html