Of Counterpoint and Counterrevolutionaries — a book review

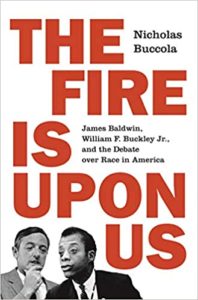

[ Emlyn Cameron reviews Nicholas Buccola’s The Fire Is Upon Us, which offers us current insight into the celebrated 1965 Cambridge Union debate between William F. Buckley, Jr. and James Baldwin ]

.

Nicholas Buccola

The Fire Is upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America

Princeton University Press, (2019)

ISBN 9780691181547

Hardback, 496pp: $29.95 / £25.00

.

“Repression is an unpleasant instrument,” – William F. Buckley, Jr.

.

There was something musical about William F. Buckley, Jr.

He was, in addition to being one of the most recognizable pundits of the 20th Century, a harpsichordist with a profound love of Bach.

“It’s not my medium,” he said in 1992, but a kind of musicality was in the warp and woof of his whole public life.

He used all his affect as an instrument in the practice of persuasion. Like Bach, he was a master of counterpoint — allowing his voice and gestures to work independent but harmonious enchantments that formed a captivating whole: the luxuriating deliberation and emphasis he put into each phrase and phoneme; the lexicon of unusual words, with their intricate, exotic sound and coy medley of connotation and insinuation; the features of his owlish face sparking and cascading with feeling, with suggestion; and his deft, musician’s hands clasping, undulating, and pirouetting through the air.

In his recent book The Fire Is Upon Us, Nicholas Buccola calls this contrapunctus, “the art of performing conservatism,” and presents it as essential to Buckley’s success in popularizing his politics. The book is Buccola’s history of the 1965 Cambridge Union debate between Buckley and James Baldwin. More broadly, it is an attempt to give an intellectual biography of both men.

With regards to Baldwin, the book is a charming introduction: It paints an inviting picture of him, with emphasis placed on his stubborn independence, ceaseless emotional curiosity, and concern that progress in American race relations extend beyond law to a substantive moral revolution of individuals. His commitment is to a confessional honesty and a future where all people, having discarded the cataract of racial prejudice, are ennobled by the recognition of their mutual humanity.

It is a spirit of reform and a kind of personal character for which Buccola has palpable admiration. The reader is not long in joining him in his respect for Baldwin: I came to the book with knowledge of Buckley and Firing Line but possessing precious little familiarity with Baldwin. I knew his name, had his essays recommended to me by a discerning friend, and had seen the debate itself, but his life and work was largely unknown to me. The man I came to know was one I could not help but like: “‘intensely serious,’ ‘delicate,’ ‘intuitive,’ ‘rash,’ ‘impractical,’ ‘rebellious,’ and ‘mercurial,’” according to the catalogue of impressions Buccola cites, he is irrepressible and tender, tough and impassioned. And, as his insistence on examining unvarnished humanity would require, he is fallible.

The apex of this balance of Baldwin’s foibles and charm is his agreement to pen an essay on the Nation of Islam for an editor with whom he has had a good working relationship: He long defers the delivery and finally sells the finished product to a different outlet, leaving the editor high, dry, and furious. And—just as one’s temple begin to throb with not a little voyeuristic impatience and disappointment—Buccola describes Baldwin sitting through the editor’s sputtering, racially charged tirade, only to lean forward at its conclusion and suggest that the man publish his resentments as an introspective essay (which he does, and which Baldwin publicly defends as the sort of honesty essential to progress). This innocent, placid response, devoted to his project of understanding, is as redemptive as it is unexpected. These episodes, and others from Baldwins life, prove just enough to please and inform, without spoiling the appetite to know more and read him firsthand.

Buckley, on the other hand, emerges the worse for this examination. It is not just that he resisted the civil rights movement (though that would be enough to contaminate his image): Buccola proposes that Buckley’s claim to a principled resistance is a mask on an unscrupulous defense of white supremacy. Buccola supports this by reference to successive arguments Buckley made for segregation, in which he shifted emphasis between, “constitutional, authoritarian, traditionalist, and racial elitist” justifications depending on what was rhetorically expedient (even when one called for conduct repudiated by one or more of the others). Buccola furthers his case by citing Buckley’s personal correspondence, highlighting evidence of prejudice (a distaste for sharing even a segregated army base with black soldiers) and self-interested cunning (apparently plagiarizing an essay he commissioned for National Review in his column before it could be published). And completes it by showing how Buckley either did not read, did not understand, or intentionally misrepresented Baldwin’s work in every public conflict he had with the man. The combined blows are debilitating, though their impact is blunted in a few respects:

First—and most superficially—Buccola is a scholar but not a great stylist. The book is easy reading, but it never approaches anything sublime in its delivery. This is made more conspicuous by the contrast to the style and skill of its subjects.

This connects to the second and more substantial limitation: Buccola’s clear condemnation of Buckley announces itself at just about every opportunity, even in the selection of verbs—words “oozed out of Buckley’s mouth slowly and [were] accompanied by a devious smile,” for instance—and the seeming absence of almost any positive descriptors for him beyond “witty” (even synonyms). Given Buccola’s thesis and the evidence he marshals, censure is legitimate. But, delivered as it is, he is unlikely to win any previously unsympathetic converts. Instead he’ll likely be suspected and dismissed by many conservatives to whom he might have most meaningfully made his argument and who could most benefit from critically examining the history of the conservative movement. (For a more skilled stylist with a similarly critical view of conservatism, who thereby also helps the reader come closer to Baldwin’s ideal of truly understanding the feelings and motivations of those one contends with, see Rick Perlstein’s Before the Storm, which artfully marries a critique of the 1960’s Right with an effective rendering of what made the movement appealing to its adherents.)

Buccola is not helped in this respect by his willingness to speculate as to the thoughts and feelings of his subjects where history has left no record upon which to draw. It aids the tone of the book (and, one imagines, pads difficult transitions), but leaves his flank rather unbecomingly exposed to assault for wishful historical thinking from critics. (Perlstein also does this occasionally, but less often, with a lighter touch, and usually without recourse to definitive phrases like “must have,” of which Buccola has availed himself.)

Finally, for people open to his argument about Buckley, the book will prove compelling, but Buccola’s broader project of a biography of ideas for these two men feels incomplete. He starts strong, with early insights into the childhoods of his subjects: how the claustrophobic poverty of Harlem and the self-hating cruelty of Baldwin’s father shaped Baldwin’s thoughts on inhumanity and self-delusion; how the pristine and hierarchical arrangement of family and staff at a young Buckley’s Connecticut home nourished his belief in “fruitful inequalities.” But, before long, the book takes to examining the arguments and ideas without such perceptive analysis of what circumstances and experiences gave them genesis or came to alter them. We are given events of the men’s lives and an evaluation of the themes of their writings, but the connective tissue of how the former inspired the latter is increasingly tenuous.

This is most apparent, in my memory, in Buccola’s statements on Buckley’s attempt to write a “big book” of political theory. Throughout the book Buccola teases that he will discuss at length Buckley’s abortive thrusts at writing a comprehensive theory of political conservatism. Given the goal of his book and the early insights into Buckley’s developing views, one expects to find a lushly realized explanation for the inability of one of recent history’s most emphatically opinionated and prolific writers to give a long statement of his beliefs.

Surely, there must be some revealing reason that a man who gave conservatism a project and a platform at its nadir and nursed it to a new zenith could not set down his own manifesto? The final reveal is disappointingly brief, descriptive instead of explanatory, and rests largely on Buckley’s preference for offensive rather than defensive debating, which Buccola had already described. This, like other aspects of the book, leaves one feeling as though potential is yet untapped in a subject which Buccola had begun so energetically to mine.

All the same, the book is a challenge to the retrospective image of William F. Buckley, Jr. that any intellectually honest person who has held affection for the man must acknowledge. I can say from firsthand experience, having often enjoyed watching that mesmerizing, sly figure on Firing Line, that it is neither pleasant nor quickly and easily done. But, it’s a testament to Buccola’s book that this painful disillusionment is also not something one is able to evade or delay.

And, as I’m sure Baldwin would insist, it is essential.

Further, for all the discomfort, there is not much surprise. It is rather like confirming a lurid suspicion one has come to feel towards an otherwise well-loved uncle.

Though I may stand at an ideological remove from them, I do not for a moment doubt the sincerity and good intentions of the average conservative and I believe in good in Buckley himself: I’ve interviewed people who attest from personal experience to his warmth and generosity. And I know he could be bracingly honest, as when—near the end of his life—he admitted without melodrama that he had reached an end to the enjoyment he took in living and was ready to be done with it.

But, he was also a man who argued that massive military spending in Vietnam was indicia of American moral superiority because it would have been cheaper just to carpet bomb indiscriminately. And who, Buccola shows, supported segregation and racial paternalism by any means necessary.

Buccola, who shares my experience of being on the political right through college (and knows the attachment to Buckley this usually entails), has performed an act of integrity and honesty with this book by bringing the ugly side of a charming man to the fore. The result could be ethically and intellectually vitalizing for everyone involved.

It is to be hoped that it will be a challenge to conservatives, and even to many liberals who have allowed more immediate conflicts to retroactively label old adversaries “reasonable.”

There was something enchantingly musical about William F. Buckley, Jr., and he cared that instruments of beauty never be abused by being put to poor use: Upon his personal harpsichord was the phrase, “Shame on anyone who plays me badly.”

We would do well not to forget his many sour notes.