Change: a poem from The Poetry of the Taliban

[ by Charles Cameron — poetry in time of war, symbolism / semiotics of blood and martyrdom, analogies with Jefferson and St Augustine, sacramental nature of reality ]

.

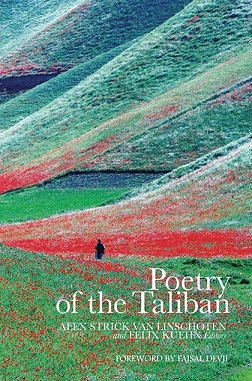

Felix Kuehn and Alex Strick van Linschoten’s book The Poetry of the Taliban (Hurst, Columbia UP) contains a remarkable poem composed in the 1990s by one Bismillah Sahar:

.

Change

The spring of change needs blood to rain down,

It requires the irrigation of the gardens with blood.

Valuing the blood of the people of the past

Requires the price of human blood.

Each drop of it has become a Nile of the dawn’s blood;

The Pharaohs want to fill the Nile with blood

Sitting here in California seven thousand miles and many cultures distant and more than a decade later, the phrase “spring of change” has an interesting ring to it – but it was likely not the not-yet-deposed Mubarak that Sahar was thinking of when he penned his lyric about the Pharaoh, but “the Oppressor” — whomever that might be. The imagery of the Pharaoh is a common enough trope, in fact, used for instance by the Taliban to describe President GW Bush in their magazine Al-Sumud [ link is to preview, relevant chapter of Master Narratives of islamist Extremism.

And while it is true that, as Asim Qureshi notes, “poetry links the ancient past with the modern day”, neither the trope itself nor the reference to the plight of the Jews in Egypt is exclusive to Afghanistan in specific or Islam in general. Indeed, Martin Luther King explicitly views himself as what theology would term a “type” of Moses when he says:

We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will get to the promised land. And I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

These sacramental bleedings of the past into the present as in a palimpsest are native to the imagination and powerful in their poetic impact, as MLK’s life, final speech and death eloquently testify.

But there is a second layer of sacramental reality at work in the poem, and it lies in the repeated mention of blood. – the transition between past an present itself being presented in terms of blood spilled in the lines:

Valuing the blood of the people of the past

Requires the price of human blood.

The past requires a price from the present, then, and that price is paid in blood.

*

The poem is six lines long, and there is not a line of it that does not contain the word blood. Again:

The spring of change needs blood to rain down,

It requires the irrigation of the gardens with blood.

Valuing the blood of the people of the past

Requires the price of human blood.

Each drop of it has become a Nile of the dawn’s blood;

The Pharaohs want to fill the Nile with blood.

*

Zeus “poured bloody drops earthwards, honoring his own son, whom Patroklos was soon to destroy in fertile Troy far from his homeland”, Homer writes in the Iliad, 16.459, and the associations of rain with tears, and of spilled blood with spilled life, are ancient and pervasive.

Blood lust, blood sacrifice – the word blood is as powerful as any in the human vocabulary, so much less abstract that birth or death yet richly associated with both, while the sight or thought of blood stirs us at some archaic level of primal imagination. And what of the “irrigation of the gardens with blood”?

The gardens, first, are paradise. Next, they are paradise on earth, perhaps in one’s own village. I have written before of my memories of:

one small white-walled mosque way out on a dry stretch of road between Herat and Kandahar and its small, lush, green garden, all these years later: whatever it was to the inhabitants of that small village, to me it was “oasis” and “paradise” in perfect miniature, and it remains so in memory.

The rivers of Islam’s paradise flow with water, milk, honey and wines: so what place has blood there?

One answer would be found in the hadith, “Know that paradise is under the shade of swords”.

In his book The Shade of Swords: Jihad and the Conflict Between Islam and Christianity, named after the hadith in question, the noted journalist MJ Akbar writes:

The only reason why a person could ever want to leave paradise for this earth would be to get martyred again. Death was only a welcome release; there was no possible deed in this life that could equal jihad in reward after death. The Prophet urged Muslims to seek Firdaus, the best and brightest part of paradise, just below Allah’s throne. Allah had reserved one hundred grades of paradise only for the martyrs. The blood of the wounded would smell like musk on the day of resurrection; and nothing could interfere with Allah’s reward.

The blood of the wounded would smell like musk…

For more on musk, blood, martyrdom and the “odor of sanctity”, see my Of war and miracle: the poetics, spirituality and narratives of jihad.

And so blood is linked to paradise by martyrdom.

*

The spring of change “requires the irrigation of the gardens with blood” the poet tells us, much as Thomas Jefferson told William Stephens Smith in a letter of November 13, 1787:

The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is it’s natural manure.

But hold on, the same trope is found in St. Augustine‘s City of God, xx.7:

Through virtue of these testimonies, and notwithstanding the opposition and terror of so many cruel persecutions, the resurrection and immortality of the flesh, first in Christ, and subsequently in all in the new world, was believed, was intrepidly proclaimed, and was sown over the whole world, to be fertilized richly with the blood of the martyrs.

And the imagery continues, in the West, into our own day. When Pope Benedict XVI visited Mexico earlier this year, he was treading on “land that was wet with the blood of martyrs” according to Mgr. Fidel Hernández Lara, Episcopal Vicar of the Mexican Archdiocese of León.

*

The very earliest Christian accounts of martyrdom, indeed, have a distinctly sacramental flavor, as one sees by juxtaposing Ignatius of Antioch (quoted by Carolyn Forche in Susan Bergman, ed., Martyrs):

I am God’s wheat ground fine by the lion’s teeth to become purest bread for Christ

with Tertullian (Apologeticum in the translation by Lewis Carroll‘s father):

The blood of the Christians is their harvest seed

*

Joseba Zulaika subtitles his book Basque Violence — which Leah Farrall kindly pointed me to — with the words “Metaphor and Sacrament”.

Sacrament is a key word for me, obviously, and for the sake of those disinclined to religion, may I point to Gregory Bateson‘s comment in the first paragraph of the Introduction to his Mind and Nature:

Even grown-up persons with children of their own cannot give a reasonable account of concepts such as entropy, sacrament, syntax, number, quantity, pattern, linear relation, name, class, relevance, energy, redundancy, force, probability, parts, whole, information, tautology, homology, mass (either Newtonian or Christian), explanation, description, rule of dimensions, logical type, metaphor, topology, and so on. What are butterflies? What are starfish? What are beauty and ugliness?

The concept of “sacrament” occupies a place of honor second only to “entropy” in Bateson’s listing.

I am not arguing the pros and cons of publishing these poems, although I side firmly with the publisher on this. Nor am I attempting to assess the poetic value of the one poem I have quoted and examined. What I am trying to do is to give that poem the kind of reading I would want to give to any poem that interested me — one that seeks out its resonances in both local and world cultures as far as my wits can manage, showing, if possible, what power it gains from archetype, authority and form… If the poem were from the South English Legendary, for instance — which expresses similar sentiments — I’d have no hesitation calling its worldview “sacramental”.

But this is a poem from Afghanistan and Islam, not from medieval Christian England, so I should perhaps explain that in my view, any perspective which views the world as a series of legible “signs from God” — ayat, in the Arabic of the Qur’an — is a sacramental view, under the definition of sacrament that calls it “an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace”.

Blood is such a sign — of life, of its value, of its continuity by descent, and of its redemptive power even in death.

It is in sensing this semiotic / sacramental quality to Islam that we begin to grasp what translations such as these can point us to, but not directly reveal.

*****

Further reading:

From today’s NYT: Why Afghan Women Risk Death to Write Poetry

Poetry reading in Afghan culture: Reading Poetry In Kandahar

Afghan poetics: Poetry: Why it Matters to Afghans? Understanding Afghan Culture [.pdf], NPS, 2009

Talib poetry as propaganda: Johnson & Waheed, Analyzing Taliban taranas (chants): an effective Afghan propaganda artifact, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 2011

And finally, Afghans Build Peace, One Stanza at a Time

May 8th, 2012 at 8:13 am

[…] can leave a response, or trackback from your own […]

May 9th, 2012 at 1:46 pm

Excellent catch, Charles, and a fine meditation.

“Change” brought to my decaffeinated mind some bloody discourse from the French Revolution. Check Camille Desmoulins (probably):

“the rivers of blood that flowed during those six months for the eternal freedom of a People of 25 million souls who had not yet been cleansed by liberty and public happiness” (source)

I remember Marat writing/hollering something like this, but can’t find a good source.

May 9th, 2012 at 2:49 pm

Hi Bryan:

.

Don’t get me started on rivers of blood, I think they’re even more common than rains of blood.

.

As a Brit, for instance, I remember Enoch Powell‘s Rivers of Blood speech, in which he said:

Then, because as you know I’m apocalyptically inclined, there’s Revelation 16.4:

And here’s a quotation from Adnan Oktar, aka Harun Yahya:

There’s a whole lot to ponder in that one!