Islamic State — hanging by a chad?

[ by Charles Cameron — light-hearted, almost science-fictional “butterfly-hurricane” question in geopolitics, with an Elkus follow-up ]

.

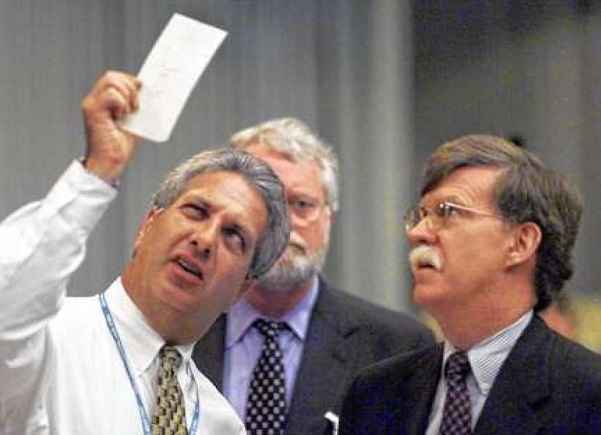

A scene from the 2000 Florida recount: Palm Beach County’s canvassing board chairman eyes a questionable ballot as Republican attorney John Bolton looks on. Image: Greg Lovett/AP

**

Is the Islamic State an “unanticipated consequence” of Bush v Gore?

Donald Trump, as quoted in Vox’s America’s unlearned lesson: the forgotten truth about why we invaded Iraq:

You do whatever you want. You call it whatever you want. I want to tell you. They lied. They said there were weapons of mass destruction, there were none. And they knew there were none. There were no weapons of mass destruction.

Without getting too far into the weeds, my question is this:

Is it fair to say that the Islamic State (aka ISIS, ISIL) was born in 2006 in response to the American invasion and occupation of Iraq, which in turn was initiated by President George W Bush, who became Commander in Chief in 2000 in a disputed election only resolved by the Supreme Court’s ruling in Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000)? And if so, looking back at the branching possibilities and eventualities that led to the creation of IS, might I plausibly suggest the Islamic State owes its very existence to a “hanging chad”?

If the Florida electoral votes hadn’t been disputed on account of flaws in the mechanical method by which they were registered, in other words, might there have been no invasion of Iraq, and hence no IS as such?

I know: this is hugely simplistic, both in terms of the election and of the drives behind Zarqawi and company — but I’m looking for an illustration of a very small digfference in “initial conditions” giving rise to a notable difference in a “later state” of a related aspect of the world system, Lorenz’s butterfly effect.

I understand that “dimpled chads” were also part of the “initial conditions” in question, but “hanging by a chad” works better as a phrase than “dimpled by a chad” — although “hanging by a dimple” has a certain charm.

Srsly, though — to what extent is our current timeline, in which IS may reasonably be viewed as a notable threat, causally connected to the resolution of a mechanical flaw in voting machine design?

**

And more seriously:

I very much appreciated Adam Elkus‘ post, Trump: The Explanation of No Explanation, and the great quote from Charles Kurzman on the Iranian Revolution from which Adam kicks off:

All of [the Iran] analyses are wrong, even if events unfold the way they predict. After all, if you make enough predictions, some are bound to look accurate. They are wrong because the outcome of this week’s events is simply unpredictable. Unpredictable means that no matter how well-informed you may be, it is impossible to know what will happen next. Moments of turmoil make a mockery of accumulated knowledge. Routine behavior, on the other hand, can be predicted. It is likely to occur tomorrow the way it occurred yesterday, with adjustments for shifts over time. But breaks from routine are a different beast altogether. The more that people feel that normal rules of behavior no longer hold, the more they search around for new rules, surveying their neighbors, collecting rumors, checking their text messages in a frantic attempt to figure out what everyone else is planning to do. Very few people are willing to be the only ones out in the street when the security forces start to advance. If people expect millions of their compatriots to demonstrate, many will want to help make history…. Such moments of mass confusion are unsettling and rare. They usually fade back into routine. Occasionally, however, they create their own new routines, even new regimes, as they did in 1978-1979. In later retelling of these episodes, especially by experts, confusion is often downplayed, as though the outcomes might have been known in advance. But that is not how Iranians are experiencing current events. Their experience, and their response to their experience, will determine the outcome.

March 21st, 2016 at 6:57 pm

For breasons I don’t understand, comments appear to have been closed on this post. I have now opened them, sinc I wanted to post a comment myself — but I’d also like to encourage any others with comments to make them. Apologies for the problem up till now.

March 21st, 2016 at 6:58 pm

Venturing just a little “into the weeds” — here’s Will McCants in a Salon interview today:

Mark you, I don’t entirely agree with McCants when he implies AQ was not using apocalyptic rhetoric for recruitment purposes..