The imagery of religion and war

[ by Charles Cameron — graphical analysis, selling bibles to teenage boys, tge Mass in time of war ]

.

Following on from my post on the work of Al Farrow, and leading towards a series of posts on ritual and ceremonial, I’d like to show you two very different images at the overlap of war and religion.

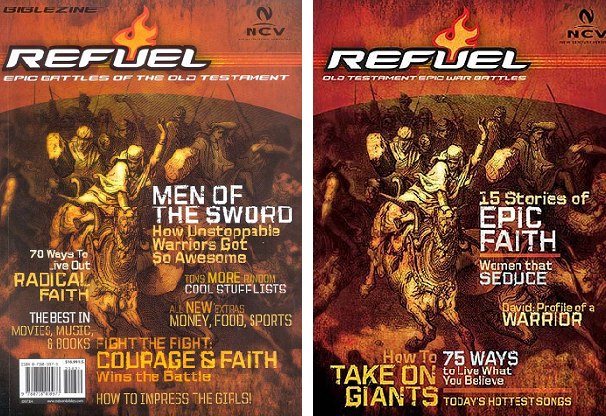

The first shows two different covers of the books of Joshua, Judges, Ruth, I & II Samuel, I & II Kings, Ezra and Nehemiah, as featured in a “biblezine” edition of the New Century Version of the Bible pitched at teenage testosterone.

Each of will have our own sense of whether that’s fun, stupid, Biblical, unBiblical, enticing, disgusting or simply uninteresting — but whatever your aesthetic and/or belief-based response, there’s a powerful lesson there in the choice of subtitles:

how unstoppable warriors got so awesome…

courage and faith wins the battle…

how to impress the girls!

how to take on giants!

women that seduce…

tons more random cool stuff lists…

I’m not a fan of this kind of thing myself, but I picked up a copy when I saw one at the thrift the other day — the one with Men of the Sword on the cover — and as someone who has done a fair amount of copy-editing in my day, was surprised to see “courage and faith wins the battle” (sic) had slipped past the editorial eyes at Nelson Books…

The New Testament in the same series is a bit better — the cover still features “dynamic stories of daring men” –but the, ahem, romantic element has been toned down a bit, with the catch phrase “class act: how to attract godly girls” replacing the Old Testament’s “how to impress the girls”.

* * *

Okay, I’m not as young as I once was, and maybe I’ve been mean enough at the expense of these people who want to market the Bible as though it was an invitation to warfare washed down with sex.

The other image I found recently comes a great deal closer to my own taste, and will serve as an excellent introduction to the idea of religious ceremonial as an oasis of peace in time of war:

Again, I suppose there may be some who will find the idea of religious ritual boring and irrelevant rather than beautiful — but it is its capacity to move us at a deep level — even (and perhaps particularly) when high tides of circumstance and emotion are breaking over us — that I wish to focus on and, to the extent that it is possible, explore and explain in some upcoming posts.

In my view, it was this kind of beauty, verging on the austere and the timeless, rather than the snazzy and faddish “impress the girls — draw in the kids” kind, that Pope Benedict XVI had in mind when he said:

Like the rest of Christian Revelation, the liturgy is inherently linked to beauty: it is veritatis splendor. The liturgy is a radiant expression of the paschal mystery, in which Christ draws us to himself and calls us to communion. As Saint Bonaventure would say, in Jesus we contemplate beauty and splendor at their source.

* * *

I am not a Catholic, though my sympathies run in that direction, and my examples of ceremonial will not be drawn only from Catholic or Christian sources — part of what i want to explore is the universal quality of ritual as a powerful source of motivation and inspiration, while another aspect has to do with the interweaving of military, religious and state symbols, but the point I would most like to make in each case is the profound impact that such symbols and rituals can have on the receptive heart.

I hope to touch on a wide range of ritual expressions, from the Requiem for a departed princely Habsburg to the Lakota sweat lodge, and from to the fire-walking ceremonial of the Mt Takei monks of Japan to the Spanish bull-fight, with a close look at the ritual surrounding coronation in my own British tradition.

For those who would like to peer deeper into these matters, I would suggest these four books:

Victor Turner, The Ritual Process

Geoffrey Wainwright, Eucharist and Eschatology

William Cavanaugh, Torture and Eucharist

Josepha Zulaika, Basque Violence: Metaphor and sacrament

The first explains “how ritual works” from an anthropological point of view, the second deals with the purposeful interweaving, accomplished within ritual, of time with the timeless, the third with the way in which sacramental transcendence is the very antithesis of torture, and the fourth with the impact of a sacramental sensibility within terrorism.

Each one is a masterpiece of intelligence and profound feeling.

September 10th, 2011 at 7:42 pm

Charles-

Interesting post. The two images are quite startling and reminded me of the clear break between the old "Soldiers Creed" and the one that has been in effect since 2003 . . .

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S._Soldier%27s_Creed

The contrast doesn’t begin to end there. I wonder how many of the comix writers have actually served in the military, have any idea about this "warrior thingie" they are talking about and the distinctions between "warrior" and "soldier" for instance, in terms of values. Ritual and ceremony would reflect this . . .

Finally what are the messages? Very different spiritual values . . .

Who are the respective audiences? Tribe, specifically young impressionable males in the first example, and entire religious/political communities in the second . . .

September 11th, 2011 at 9:17 am

Thanks, Seydlitz:

.

I’d like to be clear on the warrior / soldier distinction, since it seems to be one of those places where misunderstanding arises because popular usage differs from a more sophisticated distinction made among professionals.

.

I’m imagining that Ralph Peters‘ article, The New Warrior Class, in Parameters does a resaonable job of making the distinction you’re using, and I note that Robert Bateman in Soldiers and Warriors draws a similar distinction while adding an explicit reference to "honor" culture as a feature of the warrior. In this usage as I understand it, "warrior" is the term for someone on the wild side, driven by lust for blood and booty, as distinct from the professionalism of the contemporary warfighting "soldier".

.

I suspect that by contrast, popular usage sees the “warrior” as a fighter for whom the blast of war (borrowing from Henry V here) has stiffened the sinews and summoned up the blood — hence someone who has come into his element in warfare, and is performing at the peak of courage and excellence. And yet there’s a sort of glee to it, too, a sense that the atavistic ethos of the berserker is somehow lurking in the background, as though the warrior is a soldier who is somehow "possessed" in the heat of battle.

.

Which would then explain why the professionals are uncomfortable (to say the least) with the introduction of the more popular, positive usage of "warrior" into the Soldier’s Creed.

.

Am I getting this about right?

.

And is there a connection here with the ways in which video games — some of them science fictional / futuristic, some medieval / more fantastic — portray fighting?

.

I’m afraid you’ve opened more than one can of worms for me here — the military distinction for one, the issue of honor cultures for a second, and the impact of gaming for a third! That’s quite a trifecta…

September 11th, 2011 at 12:11 pm

Charles-

Yes, those are the distinctions I’m talking about. I remember Bateman’s article well. We discussed this topic on both the old Intel Dump & WashPost version of same frequently. On MilPub as well, and you will notice that Publius is one of my co-bloggers.

I think this transition/confusion reflects political changes in the country, the increasing trend toward strategic ambiguity due to political purposes which would not survive clear public scrutiny. In other words wars conducted for narrow private interests utilizing the state’s military assets. To conduct such wars, a pseudo-warrior caste would be appropriate. The logical next step would be the domestic version of this same notion.

And is there a connection here with the ways in which video games — some of them science fictional / futuristic, some medieval / more fantastic — portray fighting?

Definitely think so since one has to construct this tribal subculture from something and these current warriors are nothing like traditional warriors and the traditional cultures they reflect/reflected. Virtual meaning instead of actual human meaning . . . something the recent outrage in Norway may be connected to . . .

I also find some interesting connections with this topic and Weber’s Intermediate Reflection . . .

Unfortunately the entire essay is not here, but if you can get it, especially pp 224-5, I think it worth your effort.

September 13th, 2011 at 4:58 am

Hi, Seydlitz:

.

Thanks for your response, and my apologies for taking so long to get back to you.

.

Still in questioning mode, if you’ll permit me — might one say that 20th & 21st century asymmetric warfare tends to shape up as a contest between "warriors" and "soldiers"?

.

And would you say there’s a significant difference in emphasis within the "remarkable trinity" with warriors emphasizing the "primordial violence, hatred, and enmity" while soldiers put more emphasis on (are more constrained by) "war’s element of subordination to rational policy"?

.

I guess that part of what I’m getting at is my sense that "martyrdom" as a motive for fighting will draw forth "warrior" sentiment — "crusade" as a motive might do the same too, perhaps?

September 13th, 2011 at 7:01 pm

Charles-

No problem with taking one’s time responding, since reflection often adds to the discussion, don’t you think?

"Asymmetrical warfare" is essentially counter-insurgency I think, but one could argue that both Afghanistan and Iraq (2003) were "asymmetrical" as well, as was the German invasion of Yugoslavia in 1941. Basically every war has asymmetries . . . but the most blatant or those intentionally so due to the political purpose (achieved through guerrilla warfare).

Clausewitz linked the military with mostly chance, and left the subordination to politics to the government alone. I think if we follow his basic distinction in what some call the "secondary trinity" (the material elements associated by Clausewitz with the moral/codes of law elements of the remarkable trinity) between the political leadership – say the chief(s) in the tribe – and the warriors, we find the warriors more about passion since the people are not necessarily involved at all. This would also indicate a low level of material cohesion (institutions) for the political community involved, but perhaps a high level of moral cohesion for the warrior band. The warriors would provide the chief(s) with political prestige and spoils, thus enhancing/maintaining their political dominance. "Martyrdom" would provide the warrior’s death with meaning, since his story would be song around the campfires of his people "for a thousand years" . . .

"Crusade" is actually a very interesting concept, which brings up for me some very interesting questions. Can we speak of a republic (in the Western democratic sense) engaging in a "crusade" at all? Monarchies and empires can conduct crusades, since kings and emperors are thought to rule by the "grace of God", but a soldier serving a republic has first of all legal responsibilities, his ideals are always within rational legal limits. This comes out very clearly in the original Soldiers Creed btw . . .

In my opinion, politics within a republic absolutely requires a balance in regards to Weber’s ethic of responsibility and ethic of conviction, otherwise the very nature of politics can lead to the dissolution of the republic from within . . .