[ by Charles Cameron — a comment from a valued friend ]

.

My friend Daniel Bassill of Tutor-Mentor Institute has been following the Thucydides Roundtable here on Zenpundit, and sent me a comment which would probably be too long for the comment section, so I’m posting it “whole” here.

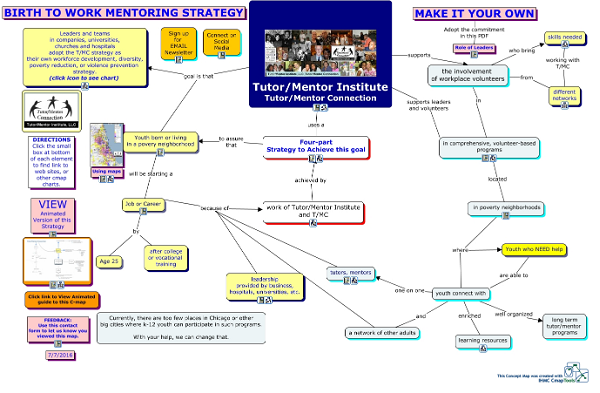

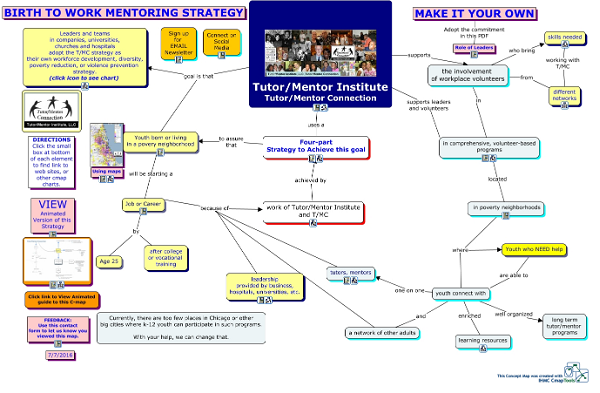

As he explains in his post, Daniel is a dedicated blogger and networker from Chicago who maps Tutor-Mentor Connections (see image above, or view full size) in an effort to provide a library of templates for similar projects in other cities.

I’m honored to offer you his guest post here.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Daniel Bassill writes:

I’d like to start out this post by saying “Thank you” to Zenpundit and Charles Cameron for luring me into your small circle of learners who have read Thucydides’ guide to The Peloponnesian War over the past 10 weeks. I started a few weeks after you all had introduced yourselves and had posted comments on the introduction and book, but finished at about the same time as the rest of you. Throughout my reading, your articles and comments greatly enhanced my understanding of what I was reading. Whoever said this is a “difficult book to read” was absolutely correct.

I’ve a long interest and majored in history in college. This book reminded me of a history of the American Civil War that I read while in 8th grade (I’m 70 now), which was about two inches thick, with small type densely packed on each page, and recounted every battle and troop movement in the entire war. I don’t know how I made it all the way through.

As I read Thucydides I used my yellow marker to highlight passages I wanted to come back to later. During the past year a few on-line friends have introduced me to annotation tools such as Hypothes.is which allows readers to highlight on-line material and comment in the margins. Others can do the same and interact with each other. That might have been an interesting way to read Thucydides with you. However, since we didn’t I put some of my highlighted text on a Hackpad over the past couple of weeks, so I could use them to help me write this post.

As I read the book, and your comments, I kept thinking of how little mankind has changed over 2400 years and how the politics and war that Thucydides was writing about relates to the current political situation in the US and the world. I was struck by how much power and influence Pericles had, as well as how much Alcibiades seemed to have. There are a few people surrounding our new president who seem to have similar power. That scares me.

Right from the introduction onward, when Thucydides wrote, “So little pains do the vulgar take in the investigation of truth, accepting readily the first story that comes to hand.” pg 15, I began to relate what he wrote 2400 years ago to how many of us make decisions today.

**

Three themes stood out in this book, that seem to still be relevant today

a) War brutalizes people, and civilians suffer the most. Throughout the book was countless reporting of massacres and pillage of captive people and surrendered cities. It seems that this hasn’t really been much of a concern for leaders until the late 1600s and Age of Enlightenment, when Rousseau and others began sharing their ideas.

b) Might makes right, and the powerful have a right to rule the weak ….this might be Teddy Roosevelt saying “Speak softly but carry a big stick” or Donald Trump saying “America First”.

c) The historical glorification of Athenian Democracy is based on a myth, in my opinion, since their ‘democracy’ only applied to the people in Athens, and not to the people in the Athenian Empire.

I want to focus on the middle of these three observations. Below are some quotes from Book One,

which I highlighted:

“For it has always been the law that the weaker should be subject to the stronger.” pg 43

“Where force can be used, law is not needed.” pg 44

“The weaker must give way to the stronger” pg 44

“Men’s indignation, it seems, is more excited by legal wrong than by violent wrong; the first looks like being cheated by an equal, the second like being compelled by a superior.” pg 44

These arguments were further developed in Book 5, where the Milian Argument was reported, and which was discussed in depth on the Zenpundit site. I highlighted these two comments.

Book 5, 16th year – The Melian Argument — (see discussion of this on Zenpundit site)

“Athenians: For ourselves, we will not trouble you with specious pretenses……. since you know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”” pg 352

“Athenians: Of the Gods we believe, and of men we know, that by a necessary law of their nature they rule wherever they can. And it is not as if we were the first to make this law, or to act upon it when made: we found it existing before us, and shall leave it to exist forever after us;” pg 354

**

I live in Chicago and grew up in the years following WW2. I’ve worked for social justice almost all my adult life, leading efforts to help inner city youth connect with adults from beyond poverty who would serve as tutors, mentors, network builders, and in other roles that helped lead youth to adult lives free of poverty.

Thus, I’ve been over exposed to “justice” and “fairness” arguments, where abused populations have

sought better treatment, apology, and even reparations from their oppressors.

Yet, little real change in condition of the poor has resulted from these challenges to oppression, and now there may be a backlash in the US as a result of the Trump election.

**

As I was preparing to write this, two other resources came to me from my web network.

I was asked to view this “potential war with China” video showing the US Empire as of 2017.

This video shows that regardless of who the US President has been, business interests, particularly the industrial-military-financial sector, for more than 150 years, maybe since the US was founded, have been driving actions that bully weaker countries and create pain and suffering for millions of people, mostly the poor. We’ve created plenty of reasons for people to hate us, and fear us. While there is growing visibility being given to protest movements, victories are small and hard to sustain.

China is not a weakling that can be pushed around. This is where DT offers much to be afraid of. Maybe China is our “Sparta” and we’re it’s “Athens”. Nothing good came from that.

The second resource is an article that traces current world events and power structure back over 2500

years to the time of Thucydides and Athenian democracy. In this section of thearticle is a comparison of two long-term

trends (demonstrated in two articles), with one titled “Plato to NATO” and another “based on the story of the epidemiology of the wetiko disease’. ”

This paragraph offers a brief summary of the two articles:

‘Plato to NATO’ separates human beings from nature and presumes we have not just the right but the duty to bend the natural world to our will. Wetiko says we are nature, and our cognitive and technological prowess means not that we have a right to dominate nature and extract all its value for our own aggrandizement, but that we have a responsibility to care for it and leave it in a better state than we found it.

This first section could have been a statement delivered by an Athenian in Thucydides’ book. The second relates to Pericles’ description of Athenian strengths, given in Book One, which concludes with “they were born into the world to take no rest themselves, and to give none to others.” pg 40

These articles prompted me to dig deeper.

**

Further research for writing this comment includes this article about Niccolo Machiavelli, who lived in France from 1469-1527. This statement shows how 15th century Europe had not changed much from BC400 Greece “Machiavelli’s era was that of the Medici family, of naked conquest by military force”

There’s an unsaid comparison to Thucydides in this statement about Machiavelli: “It has been suggested that Machiavelli wrote out of resentment, but the emotional forces that drove him were stronger than mere resentment.”

Reading further in sections summarizing Machiavelli’s book, “The Prince”, I see many ideas that could

have come directly from reading Thucydides.

I next looked to see if I could find a connection between Thucydides and Machiavelli, which led me to this article. The Influence of Thucydides in the Modern World – The Father of Political Realism Plays a Key Role in Current Balance of Power Theories, By Alexander Kemos http://www.hri.org/por/thucydides.html

This is the first paragraph of the article:

Thucydides, the Ancient Greek historian of the fifth century B.C., is not only the father of scientific history, but also of political “realism,” the school of thought which posits that interstate relations are based on might rather than right. Through his study of the Peloponnesian War, a destructive war which began in 431 B.C. among Greek city-states, Thucydides observed that the strategic interaction of states followed a discernible and recurrent pattern. According to him, within a given system of states, a certain hierarchy among the states determined the pattern of their relations. Therefore, he claimed that while a change in the hierarchy of weaker states did not ultimatley affect a given system, a disturbance in the order of stronger states would decisively upset the stability of the system. As Thucydides said, the Peloponnesian War was the result of a systematic change, brought about by the increasing power of the Athenian city-state, which tried to exceed the power of the city-state of Sparta. “What made the war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused Sparta,” Thucydides wrote in order to illustrate the resulting systematic change; that is, “a change in the hierarchy or control of the international political system.

How this affects us in 2017 is shown in this paragraph:

The impact of Thucydides’ work upon scholars of the Cold War period consists evidence for the relevance of his realist theory in today’s world. In fact, while his Peloponnesian War is chronologically distant from the present, Thucydides’ influence upon realist scholars in the post-1945 period, and in turn upon American diplomacy, is direct. Specifically, the foundations of American diplomacy during the Cold War with regard to the struggle between the two superpowers and the ethical consequences or problems posed for smaller states caught in the vortex of bipolar competition are derived from his work.

In the conclusion of this article about Machiavelli, the author wrote, “In twenty-first century liberal democracy, perhaps there is a little of the prince in everyone: it is only to be hoped that there is more than a little of the people in today’s princely political elite.”

**

In his concluding article on the Zenpundit site, A.E. Clark wrote “What we can learn from Thucydides may therefore be a purely theoretical question, if in fact no one is going to read Thucydides.”

He went on to say “Few have read this book, and few in our time will ever do so.”

I’d argue that few have read any of the articles I put on my hackpad as a result of reading Thucydides. I was motivated to read the book by reading Zenpundit articles for the past year or so, which was motivated by meeting and building a relationship with Charles Cameron, starting in about 2005. And that was motivated by my own efforts to connect more people to the work I was doing in Chicago to help build a better system of supports for inner city kids, by building better support for the tutor/mentor organizations they needed in their lives.

You can see a cycle of cause and affect.

I’m an archivist, librarian, teacher and advertiser. I put these articles on a Hackpad as a way to archive them for myself and for others. I will continue to add to this and hope others join in. I’ve been pointing to these on my Twitter and Facebook feeds for the past two weeks.

**

I’ve been hosting the http://www.tutormentorconnection.org web site and http://www.tutormentorexchange.net web site since 1998 and have been writing http://tutormentor.blogspot.com articles since 2005.

It’s probable that very few out of a planet of many billions of people have ever read any of what I’ve written.

But some have, such as Charles Cameron, and he’s made a continuous effort to encourage others to take

a look. Thus, I’m encouraged, and keep on doing this work.

Maybe that’s my take-away from this experience.

If we make the effort, maybe we can expand the band of brothers that A.E. Clark wrote about or that the writers of the Longreads site are hoping for.

And maybe that will result in helping more of us navigate the times we live in.