“Our form of government does not enter into rivalry with the institutions of others. Our government does not copy our neighbors’, but is an example to them. It is true that we are called a democracy, for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few. But while there exists equal justice to all and alike in their private disputes, the claim of excellence is also recognized; and when a citizen is in any way distinguished, he is preferred to the public service, not as a matter of privilege, but as the reward of merit.” – Pericles, The Funeral Oration

“The President of the United States of America and the Prime Minister,

Mr. Churchill, representing His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom, being met together, deem it right to make known certain common principles in the national policies of their respective countries on which they base their hopes for a better future for the world.”

– The Atlantic Charter, 1941

Adam Elkus, at Rethinking Security, makes an important point about grand strategy not requiring a great enemy:

Building a Strategy for Chaos?

….The short answer is that grand strategy isn’t something that requires an clear and equal enemy to create. But since grand strategy is something that involves a long time line, a substantially more broad subject area than war strategy, and the utilization of resources in peacetime, it makes more sense to visualize it less as an explicit plan than a collection of practices sustained over a long period of time. The policy of “offshore balancing” which Churchill mentions in this speech is one of those sets of practices.

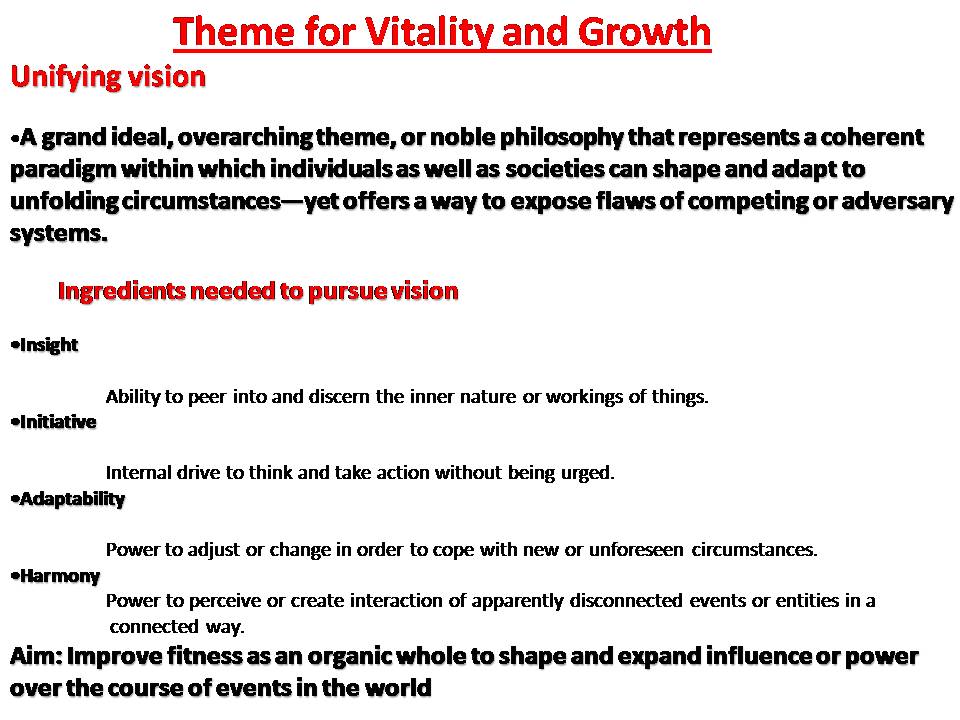

Boyd is commonly misunderstood as a tactically obsessed jet pilot whose insights mainly relate to cycling through a  decision cycle faster than the opponent. But the importance of his writings to grand strategy is undeniable. His stress on the importance of forming organizations creative and efficient enough to “destroy and create” perceptions of the external environment, increase our own connectivity and degrade that of our opponents, and the importance of establishing a “pattern for vitality and growth” all point to aspects of strategic design that focus less on marshalling resources against a specific opponent than developing a basic strategic template that can remixed for various situations under a process of “plug and play.”

decision cycle faster than the opponent. But the importance of his writings to grand strategy is undeniable. His stress on the importance of forming organizations creative and efficient enough to “destroy and create” perceptions of the external environment, increase our own connectivity and degrade that of our opponents, and the importance of establishing a “pattern for vitality and growth” all point to aspects of strategic design that focus less on marshalling resources against a specific opponent than developing a basic strategic template that can remixed for various situations under a process of “plug and play.”

In his post, Adam references Colonel John Boyd’s “Theme for Vitality and Growth” from his brief, Patterns of Conflict:

Adam went on to make an insightful observation:

The problem is that as societies grow both more structurally and interactively complex, this process grows much more difficult. That is what The Collapse of Complex Societies is about–how, if we view civilizations as computing mechanisms, how growth makes it more difficult to carry out the basic process of response to changing external conditions that is an essential part of data-processing. Moreover, even in eras of relative simplicity, the ability to aggregate enough information together to form a grand strategic design was exceedingly rare for individuals and more difficult for governments than success stories such as 19th century Prussia might indicate

Read the rest here.

I would like to extrapolate Adam’s argument about the difficulty imposed by complexity several steps further.

In considering grand strategy, historically, except for the Romans during their golden age, state actors, even vast empires like the Soviet Union or Great Britain, never approximated a closed system that could operate without reference to rivals who could potentially present an existential threat, singly or in combination. While the Pax Romana represents the rare outcome of a successful grand strategy, most great powers wrestled with imposing their will on both their rivals – but also on the geopolitical environment or “system” in which they operated.

What do I mean by the “system”? The explicit and implicit cultural and diplomatic rule-sets; the “rules of the game” by which powers interacted; the geoeconomic structures and patterns that were larger than any particular political entity and imposed constraints upon them, even the chance-based variables of natural resources and technological level which had a determining effect upon formulation of policy and strategy. The relationship between the architect of a grand strategy, his rivals and the world in which all were forced to operate consisted of a multiple variable feedback loop, not a diktat with a binary set of possible results.

I woud now like to make two points.

First, to use an analogy from the biological sciences, grand strategy enunciated by a great power is a process of geopolitical co-evolution. There is an effort in grand strategy to impose over time one’s political will upon others to shape the “battlespace”, the sphere of influence, the hegemonic dominion to a state of affairs favorable to the state actor. Often, this is done by military force in times of crisis but over the long term, economic and diplomatic factors, all of DIME really, weigh heavily on the outcome. The process is never a one way street, even for actors who are considered to be largely triumphant. It is coevolutionary. If you gaze into the abyss, the abyss will gaze into you.

The early Roman republicans, much less Cato the Younger, would have been viscerally appalled by the Empire of Late Antiquity with its’ Teutonic Masters of the Horse in place of citizen- Praetors and Imperators. The Founding Fathers would be amazed by the condign dominance of the United States as a global titan but dismayed by the truckling servility, the lack of economic independence and the sheepish passivity of Americans whose citizenship is largely nominal. Ancient Chinese sages might feel much the same about hybrid capitalist-communist China of 2010.

Secondly, sustaining the national or group identity is a critical component of grand strategy that makes it a different, more expressly political/cultural exercise than crafting strategy as Clausewitzians use the term as being driven by policy. Grand strategy should guide policy formulation because it is not just a set of concrete structural ends, or a laundry list of “vital interests” but a constructive, values-laden, attractive, motivating, civilizational narrative. An ideal or cultural identity for which men and societies are willing to go to war, to stand, fight and die. As Thomas P.M. Barnett once put it, for a “Future worth creating“. Grand strategy is a defiant clarion call of civilizational supremacy, marshalling those who will fight for that which is not, but could be.

But if you gain the whole world, while losing oneself, have you won? Or lost?

A victorious grand strategy shapes others while preserving – or expanding the reach of – the core identity of cultural-political community engaged in the struggle for autonomy for itself and dominion over the environment. Some changes though are inevitable despite the best of intentions. Exercising power carries with it a price and the piper must be paid.

Following Boyd, the more attractive our vision, the “noble philosophy” we offer up to others and the more consistently we practice that which we preach, the greater our reach while remaining true to ourselves – thus demoralizing our adversaries. The more we trade on our souls, compromise our principles, turn away from threats and contradict our professed ideals, the less we have. Power is useful but it is transient. The exercise sweet, but the cost dear.

Power runs through our fingers like water. What did we give for it? What did we gain? Who are we now?

That is grand strategy.

decision cycle faster than the opponent. But the importance of his writings to grand strategy is undeniable. His stress on the importance of forming organizations creative and efficient enough to “destroy and create” perceptions of the external environment, increase our own connectivity and degrade that of our opponents, and the importance of establishing a “pattern for vitality and growth” all point to aspects of strategic design that focus less on marshalling resources against a specific opponent than developing a basic strategic template that can remixed for various situations under a process of “plug and play.”

decision cycle faster than the opponent. But the importance of his writings to grand strategy is undeniable. His stress on the importance of forming organizations creative and efficient enough to “destroy and create” perceptions of the external environment, increase our own connectivity and degrade that of our opponents, and the importance of establishing a “pattern for vitality and growth” all point to aspects of strategic design that focus less on marshalling resources against a specific opponent than developing a basic strategic template that can remixed for various situations under a process of “plug and play.”