[by Mark Safranski / “zen“]

ZP is pleased to bring you a guest post by Pete Turner, co-host of The Break it Down Show and is an advocate of better, smarter, transition operations. Turner has extensive overseas experience in hazardous conditions in a variety of positions including operations: Joint Endeavor (Bosnia), Iraqi Freedom (2004-6, 2008-10), New Dawn (Iraq 2010-11) and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan 2011-12).

ON REPRESENTATIVE DUNCAN HUNTER’S QUESTIONS ABOUT HTS

by Pete Turner

Today I was sent this USA Today article about Rep. Duncan Hunter (R-Ca) and Human Terrain System with a request for comments. An excerpt:

….A critic of the program, Rep. Duncan Hunter, a California Republican and member of the Armed Services Committee, demanded answers about the program from Acting Army Secretary Patrick Murphy in a letter sent Monday. Hunter noted “striking similarities between the two programs” and called on the Army to explain how the Global Cultural Knowledge Network differed from Human Terrain System. He also asked for an accounting of its cost and the number of people it employs.

“Unless the Army can show real differences between programs, then there should be no doubt that this constitutes a blatant attempt to rebrand and reboot a failed program under another name and a launch it with a reworded mission statement,” Hunter told USA TODAY on Tuesday. “What’s obviously lost on the Army is that it wasn’t just the implementation of HTS that was the problem, it was the whole thing, to include the program’s intent and objective.”

I have no faith in TRADOC’s ability to get Human Terrain System or HTS 2.0 any more right than last time. The program was full of prima donnas, liars and academics who lacked the ability to relate to the military and commanders. Also, commanders aren’t trained in how to best use HTS assets either – and that matters. For example:

COL: “Pete, I want you to tell me who the most influential person in our region is….can you do that?”

Pete: “Yes Sir, I have the answer already…it’s you…until the people recognize their own governmental leaders, police and military, our focus has to be in ramping your influence down while we enable them to ramp up, Sir.”

That statement is the essence of what an HTS does – we identify and translate the intersection of the ramps. There is no book on how to do it well. The ground truth is where the best work is done. It’s a shame that Rep Duncan Hunter and DoD cannot see that.

For those who aren’t familiar with my work, I have 70+ months of time working in combat zones. I’ve worked most of this time at the lowest level interacting with locals on well over a 1000 patrols. A great deal of this time I worked in the HTS program mentioned in the article.

Rep D. Hunter questioned the need and was critical of the original HTS program. Like any program we absolutely had our share of fraud, waste and abuse. Here’s the thing…the HTS program even when legitimately run is expensive. Units work hard, long hours and a relentless schedule. On numerous occasion, I’d work a 20 hour day followed by an 18 hour day followed by a string of 16 hour days. An 84 hour week is the minimum I’d work. Working at the minimum pace of 12 hours a day 7 days a week, a person will “max out” on their federal pay for the year and accumulate “comp time” or paid days off.

Since there are always things to do, lives at stake, command directives to pursue…missions to go on, planning to complete, analysis to run, reports to write, meetings to attend…it’s not hard to work 90+ hours a week and be seen as not doing enough. How about this – some units will practice for a meeting for hours prior to the actual meeting? If a unit is going to spend 6 hours prepping for and executing a meeting, that’s just ½ of a day…yes, legitimate work will result in paid leave.

If my patrol leaves at 3AM because there is a full moon and we move up and over a mountain arriving at a village before dawn…then spend the rest of the morning patrolling more and finally return to base at 2 in the afternoon…I still have to report on what I saw, a report may take 3-4 hours to write….and then prep for the next day’s patrol…unless your unit is doing 2 patrols a day.

I recall one specific time when a brigade from the 82nd that I was attached to was going to rotate home. The brigade commander wanted to provide the new unit with the best possible handoff in terms of data, relationships etc. To facilitate this handoff, my team was tasked to improve a “smart book” of dossiers on prominent Iraqis. At one point I sat in the same chair for 24 hours writing, rewriting and then updating the book…simply because we HAD to work – the books weren’t getting better, just being constantly reworked.

Why do I bring this up? Two reasons: First, the 82nd works HARD and if one is attached to them, that person works hard too, or suffers from irrelevance. The 82nd spent a lot of taxpayer money on HTS people writing those books with the best intentions. Secondly, the next unit came in and literally, never used the books. When I asked why, the new unit said, “we really don’t do that.”

When Rep Hunter originally questioned, the need for the program, I reached out to him to illustrate how when done properly, HTS work saves money and creates the kind of wins that unit’s cannot do without a HTS capability. I also sent several notices to the my district’s congressional rep Mr. Mike Thompson. Both he and Mr Duncan are veterans; I thought, surely they’d value my unique “ground truth” based knowledge. I was wrong, both representatives ignored my offer to provide feedback.

The answer to Rep Duncan’s question about the need for this program is this:

Commanders need an outside element to translate what the US is doing for locals; in this case Afghans. Meanwhile the HTS person also translates back to the US military what the locals are experiencing. What an HTS person really does is works as a cultural translator allowing the different sides to understand the reality of their “partner.”

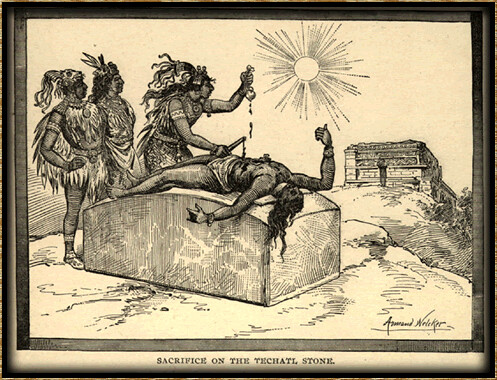

I worked in a valley that had a steep narrow canyon. The local US Army agricultural development team (ADT) a truly myopic, xenophobic program that commonly created instability more than anything else, decided to build a check dam. The dam was supposed to elevate the water in the river high enough to charge the irrigation ditches that ran the length of the river valley. Over the course of 18 or more months the ADT fought with locals to improve the dam, while the locals rejected it and attempted to destroy it on several occasions.

The Dam Project

I was able to talk to locals who reasonably explained why the dam was an issue. Simply put, they didn’t want it – and it was predicted to fail as soon as the first rain came. Further, the region had an Afghan leader chosen to handle water issues for the families. He agreed that the dam was a bad idea; and also predicted it would fail with the first rain. We never effectively engaged the water elder–instead the ADT insulted this person and ignored his position and influence with the farmers. A commander can’t know these things without an HTS person on the ground studying the human terrain.

I spoke with the ADT engineer responsible for the final “upgrade” to the dam. I mentioned the concerns of the people and the water elder about the long term viability of the dam, which was visibly failing – the ADT hydrologist said, the elder may be right. Exacerbating this further, the dam project was done, updated and repaired all without any planning with the local Afghan governor. All in all, the dam cost well in excess of $100k

Then the first rain came…

If one was to look at the ADT reporting, the dam was a hit. It was accomplishing great things for the valley’s farmers. Without an human terrain operator like myself, the ADT and the local US commander likely would never have found out how miserably they’d failed. Rep Duncan, you want to fix things? Give me a call and I’ll show you where the money is really being wasted.

It gets worse…not only did the dam fail; when locals began to engage the governor about his plan to deal with the dam (this BTW is a small win, as most farmers a month prior saw no benefit from the government) the governor had no capacity to change anything. This in effect confirmed for many locals that the governor had no ability to help them and therefore, the Taliban would remain the dominant force in the region. Ultimately, the ADT had closed the books on the region and meanwhile security further eroded. Our efforts to create capacity resulted in us undermining the fledgling power of the governor. Within a few months of my leaving the region, a district once considered to be a model of stability, had three service members assassinated by their Afghan partners.

Without an HTS asset, we never learn these lessons. This is one of dozens of tales I was able to illustrate as an HTS operator. Of course, since Reps Duncan and Thompson can’t be bothered with the ground truth – its all fraud waste and abuse, isn’t it?