Islamic State vs Saudi Arabia — Cole Bunzel’s new paper

Friday, February 26th, 2016[ by Charles Cameron — contextualizing IS in terms of KSA, Abd al-wahhab and the Prophet, also an interior / eternal aspect of the “end times” ]

.

Cole Bunzel, speaking with Charlie Rose

**

As a poet, I keep my eyes peeled for the superposition of opposites in a small space. John Donne‘s great phrase, “At the round earth’s imagin’d corners, blow / Your trumpets, angels” manages to superpose the imaginary and actual, sacred and soon-to-be profane, flat earth and globe, in just four words, Shakespeare is even more concise with Rosalind‘s “you insult, exult, and all at once” in As You Like It, and Dylan Thomas is after the same effect in his line “Curse, bless me now with your fierce tears, I pray” in Do Not Go Gentle.

The poet is after a world in miniature, the balance of contraries. And so it is that I was stopped dead in my tracks on reading Cole Bunzel‘s sentence at the end of the second paragraph of the Introduction to his new paper, The Kingdom and the Caliphate: Duel of the Islamic States:

One of those territories increasingly in its sights is Saudi Arabia, home to Islam’s holiest places and one-quarter of the world’s known oil reserves.

Bunzel is a PhD student writing a paper for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, so I’m expecting to be informed, yes, but this immediate, strong duality catches my attention — and it’s followed immediately with another at the start of his third paragraph:

The competition between the jihadi statelet and the Gulf monarchy is playing out on two levels, one ideological and one material.

The ideological and the material — holy places and oil reserves — in both phrasing we can recognize the world in a nutshell. And Bunzel will sharpen that sense of duality throughout, by contrasting Saudi Arabia, where possession of the resources has arguably warped the purity of creed as Abd al-Wahhab prtoposed it, with the Islamic State, which at least as it sees itself has maintained that “original” purity, and is now in a struggle for the resources to propagate its vision of Tawhid across the face of the earth.

As Bunzel puts it:

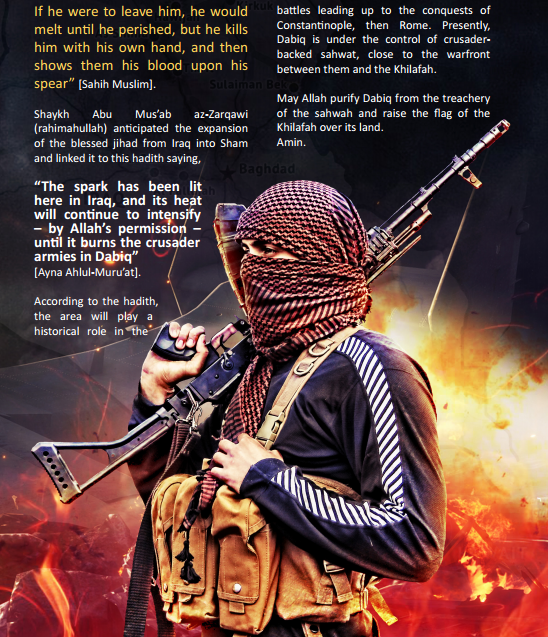

The comparison worth noting is the one in the minds of the Islamic State’s jihadi thinkers, the idea that Saudi Arabia is a failed version of the Islamic State. As they see it, Saudi Arabia started out, way back in the mid-eighteenth century, as something much like the Islamic State but gradually lost its way, abandoning its expansionist tendencies and sacrificing the aggressive spirit of early Wahhabism at the altar of modernity. This worldview is the starting point for understanding the contest between the kingdom and the caliphate, two very different versions of Islamic states competing over a shared religious heritage and territory.

Kingdom and caliphate: again, the elegant duality.

**

Let’s see now, how this duality — proclaimed, indeed in Bunzel’s title, The Kingdom and the Caliphate: Duel of the Islamic States — plays out in his analysis:

The new king has described Saudi Arabia as the purest model of an Islamic state, saying it is modeled on the example of the Prophet Muhammad’s state in seventh-century Arabia. “The first Islamic state rose upon the Quran, the prophetic sunna [that is, the Prophet’s normative practice], and Islamic principles of justice, security, and equality,” he stated in a lecture in 2011. “The Saudi state was established on the very same principles, following the model of that first Islamic state.” What is more, the Saudi state is faithful to the dawa (mission) of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, meaning Wahhabism, upholding the “banner of tawhid” and “calling to the pure faith — pure of innovation and practices having no basis in the Quran, sunna, and statements of the Pious Forbears.”

The Islamic State makes the same claims for itself. It, too, models itself on the first Islamic state, as its early leadership stated upon its founding in October 2006: “We announce the establishment of this state, relying on the example of the Prophet when he left Mecca for Medina and established the Islamic state there, notwithstanding the alliance of the idolaters and the People of the Book against him.” Another early statement appealed to the Wahhabi mission, claiming that the Islamic State would “restore the excellence of tawhid to the land” and “purify the land of idolatry [shirk].”

Compare and contrast — it’s one of the oldest tricks in the intellectual book, and maybe the most powerful.

And it’s right there — the material in conjunction with the spiritual — from the beginning:

This first Saudi-Wahhabi state was the product of an agreement reached between the chieftain Muhammad ibn Saud and the preacher Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab in the small desert oasis of Diriyah in central Arabia. The two leaders agreed to support each other, the Al Saud supporting the Wahhabi mission and the Wahhabi missionaries supporting Saudi political authority.

Religion and politics, politics and religion. Church and state, we might say, Caesar and God.

**

But I shouldn’t inflict too much by way of this “dual” poetic formalism on my readers…

Bunzel details the three states at the juncture of Wahhabism and the House of Saud — “the first (1744–1818), the second (1824–1891), and the third (1902–present)” and proposes that we are now witnessing somethiung not unlike the genesis of a fourth:

Indeed, the Islamic State is a kind of fourth Wahhabi state, given its clear adoption and promotion of Wahhabi teachings.

But while the opposition Bunzel studies is between his third and fourth variants of Wahhabi-statehood, the analogy claimed in each of those cases is with the first.

Given that the House of al-Saud is the military partner of al-Wahhab-derived theology in the first three cases, their claim to contimuity with the first Wahhabi state, and thus also with the Prophet’s original state in Medina, is readily made:

The new king has described Saudi Arabia as the purest model of an Islamic state, saying it is modeled on the example of the Prophet Muhammad’s state in seventh-century Arabia. “The first Islamic state rose upon the Quran, the prophetic sunna [that is, the Prophet’s normative practice], and Islamic principles of justice, security, and equality,” he stated in a lecture in 2011. “The Saudi state was established on the very same principles, following the model of that first Islamic state.” What is more, the Saudi state is faithful to the dawa (mission) of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, meaning Wahhabism, upholding the “banner of tawhid” and “calling to the pure faith — pure of innovation and practices having no basis in the Quran, sunna, and statements of the Pious Forbears.”

Similarly, Bunzel notes, IS has claimed since its beginnings in late 2006:

We announce the establishment of this state, relying on the example of the Prophet when he left Mecca for Medina and established the Islamic state there, notwithstanding the alliance of the idolaters and the People of the Book against him.

While IS aspires not only to theological continuity but to a greater theological fidelity to al-Wahhab’s original Wahhabi state than the current regime, it regards the current state of the House of al-Saud as depraved and corrupt, in a manner quite different from the Prophet’s Medinan state — ridiculing it as “Al Salul” after “a leader of the so-called ‘hypocrites’ of early Islam who are repeatedly denounced in the Quran.”

The Saudi claim to be a Wahhabi state largely derives, let me suggest, from the al-Saud side of the original Wahhabi-Saudi alliance, while the Islamic State’s claim rests uniquely on the doctrine of al-Wahhab, viewed as a reformer who returned Islam to its original purity.

Indeed, Bunzel can cite an article “distributed by the Islamic State’s semiofficial al-Battar Media Agency” as describing thee IS mission as “an extension of Sheikh [Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab’s] mission.” And the similarity extends not just to that mission, but also to the opposition it arouses:

The author, who goes by Abu Hamid al-Barqawi, drew attention to the similar accusations made against the two states by their respective enemies, namely accusations of excess in the takfir (excommunication) and killing of fellow Muslims. He noted that both states were denounced as Kharijites, an early radical Muslim sect.

Thus we see, from the perspective of the Islamic state, another dualism repeating itself across history: this time between the original Companions of the Prophet and the abhorred Kharijite heretics, and the present followers of al-Baghdadi’s claim to the Caliphate and the Kharijite House of al-Saud.

In a further twist, both the House of al-Saud and Al-Qaida’s local branch, Jabhat al-Nusra, have accused the Islamic State precisely of being Kharijites, the Saudi Sheikh Abdul Aziz Al ash-Sheikh terming IS Kharijites who “believed that killing Muslims was not a crime, and we do not consider either of them Muslims”, while Jabhat’s spiritual adviser, Sami al-Aridi, has said:

The swords that God ordered us to use are many. One of these swords is the one pointed at Kharijites. This group [IS] has provided solid proof that it is Kharijite.

And who, again, are the Kharijites? I have quoted before now this hadith reported in Abu Dawud:

The Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, said, “There will be dissension and division in my nation and a people will come with beautiful words but evil deeds. They recite the Quran but it will not pass beyond their throats. They will leave the religion as an arrow leaves its target and they will not return until the arrow returns to its notch. They are the worst of the creation. Blessed are those who fight them and are killed by them. They call to the Book of Allah but they have nothing to do with it. Whoever fights them is better to Allah than them.”

**

There is, of course, much more to Bunzel’s paper than I have captured here, but I would like to comment on one final issue, the one which I always return to — that of the end times, or eschatology. Bunzel writes:

The Islamic State’s apocalyptic dimension also lacks a mainstream Wahhabi precedent. As William McCants, a scholar of jihadism at the Brookings Institution, has set out in detail in a book on the subject, the group views itself as fulfilling a prophecy in which the caliphate will be restored shortly before the end of the world. While the Saudi Wahhabis and the Islamic State Wahhabis share an understanding of end times, only the latter view themselves as living in them.

In the light of our discussion above of the respective Islamic States of the Prophet himself at Medina, Abd al-Wahhab in conjunction with the original Saudi state, and the current Wahhabism of Baghdadi’s Caliphate, this naturally raises the question as to whether the Prophet’s Medina was an eschatological state, a topic which David Cook briefly addresses in the Introduction to Muslim Apocalyptic in his Studies in Muslim Apocalyptic:

The research of some scholars has indicated that Muhammad himself was impelled by a powerful belief in the proximity of the Last Day. For example, the Prophet is quoted as saying that some that see him will live to see the Dajjal (the Muslim anti-Christ).

Cook footnotes this claim with the following intriguing comment:

Though I do not wish to overspeculate as to the significance of this belief upon Muslim history, one cannot help but notice that the question of why Muhammad did not designate a successor is frequently asked. Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that he genuinely did not believe that there would be time enough before the end of the world for anyone to succeed him. The very fact of some sort of will would show a lack of faith in the immediacy of the End.

Christianity, similarly, can be seen as an apocalyptic movement from its origin, with Christ similarly telling his followers “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand: repent ye, and believe the gospel” (Mark 1.15) and “Verily I say unto you, That there be some of them that stand here, which shall not taste of death, till they have seen the kingdom of God come with power” (Mark 9.1).

**

Here if I may, I shall turn speculative and poetic.

In his extraordinary reading of the Quran in The Apocalypse of Islam, Norman O Brown views the history of Islam as comprising “a series of decisive (requiring decision) apocalyptic moments, moments that will recur throughout a history that has no set end-point”:

These moments must (through the action, the cooperation with God’s call by the believer’s response) break through the crust of the familiar way of doing business (whether globalized or traditional), and lead one to an action that will necessarily be historical and personal (towards purification) because the drive of God’s will is always towards unity, both within and without.

The Islamic world today clearly anticipates the end times in the future, perhaps near, perhaps far, its date and hour necessarily unknown, and expects it to come upon us after various notable signs of the time have occurred –- the Shia with the return of the expected Twelfth Imam, now in ghayba or occultation, and the Sunni with the coming of the Mahdi and of the Prophet Issa (Jesus).

With regard to those notable signs, at 47.18 in the Arberry translation the Quran asks:

Are they looking for aught but the Hour, that it shall come upon them suddenly? Already its tokens have come; so, when it has come to them, how shall they have their Reminder?

Brown quotes Louis Massignon as calling Sura 18, The Cave, “the apocalypse of Islam” — and further suggests we should not apply enlightenment notions of linear time to a book, the Quran, which is itself both Revelation and Word. The poet Allama Muhammad Iqbal, in a phrase reminiscent of earlier Jewish and Christian texts, says of the Quran, “whole centuries are involved in its moments.”

Brown writes:

There is an apocalyptic or eschatological style: every Sura is an epiphany and a portent; a warning, “plain tokens that haply we may take heed” (XXIV, 1). The apocalyptic style is totum simul, simultaneous totality; the whole in every part. Hodgson on the Koran: “almost every element which goes to make up its message is somehow present in any given passage.”

Mathematicians will no doubt note the resonance here with the principle of holography, Buddhists with the Hua-Yen concept of the Jewel Net of Indra.

Brown, again referencing Massignon, who along with Henry Corbin was one of the major sources of his insight into Islam:

Massignon calls Sura XVIII the apocalypse of Islam. But Sura XVIII is a resume, epitome of the whole Koran. The Koran is not like the Bible, historical; running from Genesis to Apocalypse. The Koran is altogether apocalyptic. The Koran backs off from that linear organization of time, revelation, and history which became the backbone of orthodox Christianity … Islam is wholly apocalyptic or eschatological, and its eschatology is not teleology. The moment of decision, the Hour of Judgment, is not reached at the end of a line; nor by a predestined cycle of cosmic recurrence; eschatology can break out at any moment.

The End is in the Beginning — or as Eliot would have it, “And the end and the beginning were always there. Before the beginning and after the end.”

In the first sura on the Quran, al-Fatihah, The Opening, God is described first as “the All-merciful, the All-compassionate” (1.3), then as “Master of the Day of Doom” (1.4), and only then is there mention of humanity, in the words “Thee only we serve; to Thee alone we pray for succour” (1.5). According to a hadith reported in Tirmidhi, the Prophet said, “I was sent in the presence of the Final Hour.” To be present at the End, to be present at the Beginning — both are reminiscent of Christ’s extraordinary trans-temporal remark — perhaps the deepest teaching in the gospels, a true koan —

Before Abraham was, I am.