On two, one, seven plus or minus, and ten – towards infinity

Monday, July 29th, 2013[ by Charles Cameron — a few quirky thoughts about graphs and analysis ]

.

Two eyes (heads, ideas, points of view) are better than one.

**

When I worked as senior analyst in a tiny think-shop, my boss would often ask me for an early indicator of some trend. My brain couldn’t handle that — I always needed two data points to see a pattern, and so I coined the mantra for myself, two is the first number. When the American Bankers Association during the Y2K scare wrote and posted a sermon to be delivered in synagogues, churches and mosques counseling trust in the banking system it was a curiosity. When the FBI, in response to the same Y2K scare, put out a manual for chiefs of police in which they provided input on the interpretation of the Book of Revelation, the two together became an indicator: they connected.

My human brain could see that at once — non-religious authority usurps theological function, times two.

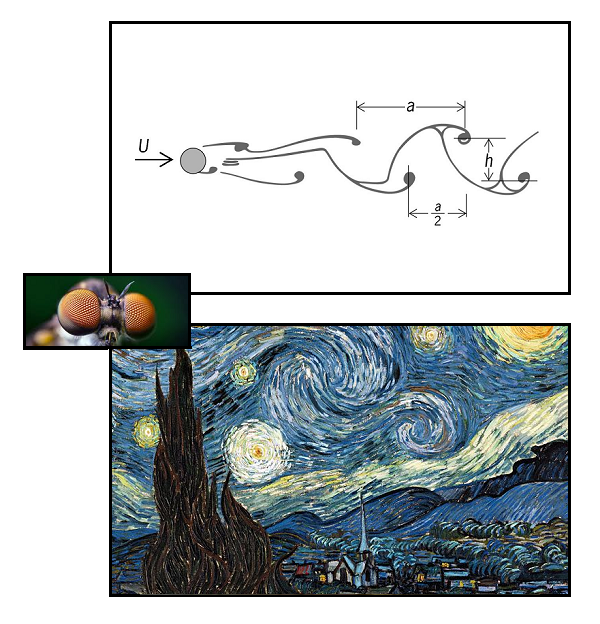

For what it’s worth, the Starlight data-visualization system we used back then (1999) couldn’t put these two items together: I could and did.

**

To wax philosophical, in a manner asymptotic to bullshit:

One isn’t a number until there are two, because it’s limitless across all spectra and unique, and because it is its own, only context.

One isn’t a number unless there’s a mind to think of it — in which case it’s already an abstraction within that mind, and thus there are, minimally, two. At which point we are in the numbers game, and there may be many, many more than two — twenty, or plenty, or plenty-three, or the cube root of aleph null, or (ridiculous, I know) infinity-six…

Go, figure.

Two is the first number, because the two can mingle or separate, duel or duet: either way, there’s a connection, a link between them.

Links and connections are where meaning lies — in the edges of our graphs, where two nodes seamlessly integrate, much as two eyes or two ears give us stereoscopic vision or stereophonic sound, not by abstracting one from two by skipping the details that make a difference, but by incorporating the rich fullness of both to present a third which contains them fully via an added dimension of depth.

That’s the fundamental reason that DoubleQuotes are an ideal analytic tool for the human mind to work with: they’re the simplest form of graph — the dyad — populated with rich nodes and optimally rich associations between them.

**

**

Cornelius Castoriades wrote:

Philosophers almost always start by saying: “I want to see what being is, what reality is. Now, here is a table; what does this table show to me as characteristic of a real being?” No philosopher ever started by saying: “I want to see what being is, what reality is. Now, here is my memory of my dream of last night; what does this show me as characteristic of a real being?” No philosopher ever starts by saying “Let the Requiem of Mozart be a paradigm of being”, and seeing in the physical world a deficient mode of being, instead of looking at things the other way around, instead of seeing in the imaginary, i.e., human mode of existence, a deficient or secondary mode of being.

When I specified above “the simplest form of graph — the dyad — populated with rich nodes and optimally rich associations between them” I was offering a Castoriades-style reversal of approach, in which our choice of nodes is determined not by their abstraction — as single data points — but by their humanly intuited significance and rich complexity. Hence: anecdotes, quotes, emblems, graphics, snapshots, statistics — leaning to the qualitative side of things, but not omitting the quantitative. And their connection, intuited for the richness of the parallelisms and oppositions between them.

Often the first rich node will be present in the back of the mind — aviators wanting to learn how to fly a plane, but uninterested in how to land it — when the second falls into place — when a student asks a diving instructor to teach the diving technique, with no interest in learning to avoid the bends while coming back up. And bingo — the thing us understood, the pattern recognized, and an abstraction to “one way tasks” — including “one way tickets” established.

Let’s call that first node a “fly in the subconscious”. I’d love to have been a fly in the subconscious when SecDef Rumsfeld told a Town hall meeting in Baghdad, April 2003:

And unlike many armies in the world, you came not to conquer, not to occupy, but to liberate and the Iraqi people know this.

Because I could have chimed in cheerfully in the very British voice of General Sir Frederick Stanley Maude, in that different yet same Baghdad in 1917:

Our armies do not come into your cities and lands as conquerors or enemies, but as liberators…

Oh, the echo — the reverb!

**

The ideal number of nodes in the kind of graph I’m thinking of is found in terms of the human capacity to hold “seven plus or minus two” items in mind at the same time — thus, with a slight scanning of the eyes, a graph with eight to twelve nodes and twenty or so edges is about the limit of what can be comprehended.

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life, infinitely rich in meaning and instruction, has ten nodes and twenty-two edges. Once taken into the mature human mind, there is no end to it.

The value of a graph composed of such rich nodes and edges lies in the contemplation it affords our human minds and hearts.

**

Two, being the simplest number, will probably give you the richest graphs of all…

Art, in the person of Vincent Van Gogh, meet science, in the person of Theodore von Kármán.