Phineas Priesthood 2: The Tanakh

[ by Charles Cameron — continuing exploration of the Phineas story as it leads to the recent Larry McQuilliams incident among others ]

.

I

Paradise is depicted in many traditions as a garden — indeed the very word “paradise” (pardes) means “garden” or “orchard” in Hebrew. It is a place where the divine presence “walks with man in the cool of the day” — glorious phrase — a green and fruitful garden, rich in beauty and tranquility, where the purity of love is unsullied by despair or hatred.

In our scriptures, myths and rituals, we give expression to all that is noblest and most generous in our nature: the “peace that passeth all understanding” manages somehow to cross the great Cartesian divide between mind and body, promising us both inner peace of mind, and external relief from war and strife.

All is not well in this garden, however. Along with the refreshing breezes and the sounds of voices lifted in praise, our scriptures and religions also offer us reasons for killing and warfare, divinely sanctioned injunctions to the sword as well as to peace. One of the recorded sayings of Muhammad teaches that Paradise is found under the shade of swords.

Christ, too, is reported to have said he “came not to bring peace, but a sword”.

Like a perennial landmine in paradise garden, the story of Phineas (also spelled Phinehas or Pinchas) lies await in the Tanakh / Old Testament for some reader to take a wrong step and explode it once again.

Introducing this series in Phineas Priesthood I: Larry McQuilliams, I said:

Since I shall be discussing how the tale of Phineas / Pinchas / Phinehas has been used as offering divine scriptural sanction for acts of religiously-motivated killing, I shall chiefly focus on the negative implications of the tale .. Accordingly, I’d like to invite my friends in the Jewish and Christian scholarly communities, in particular, to assist me in the comments section by suggesting alternative ways of reading a story which in its most literal interpretation has been the cause of untimely and hateful deaths

That goes for the series as a whole. In later posts in this series I shall follow the trail of Phineas (the lone wolf) and touch on the Maccabees and Zealots (his “group” equivalents), first in the ancient world, and then more recently.

II

The story of Phineas is told in the book of Numbers / Bamidbar, chapter 25:

While Israel dwelt in Shittim the people began to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab. These invited the people to the sacrifices of their gods, and the people ate, and bowed down to their gods. So Israel yoked himself to Baal of Peor. And the anger of the Lord was kindled against Israel; and the Lord said to Moses, “Take all the chiefs of the people, and hang them in the sun before the Lord, that the fierce anger of the Lord may turn away from Israel.” And Moses said to the judges of Israel, “Every one of you slay his men who have yoked themselves to Baal of Peor.” Take all the chiefs of the people, and hang them in the sun before the Lord.

In all likelihood, I must have heard this passage read aloud at least once before the age of eighteen in the chapels of the British boarding schools I attended — yet I have no vivid childhood memory of a God who encourages mass hangings out in the open air. The God of my childhood and schooling was caring, loving, far-seeing (which I understood to be one of those divine omni-attributes, thus distinguishing him from my parents or teachers), and wise.

Thinking back on my time as a choir-boy, I imagine those sonorous phrases about the anger of the Lord, delivered in the splendid prose of the King James Version, must have rolled right over me, like Alan Bennett‘s reading of the text, “My brother Esau is an hairy man, but I am a smooth man” in his sermon in the satirical revue, On the Fringe — something along these lines:

And the Lord said to Moses, “Take all the chiefs of the people, and hang them in the sun before the Lord, that the fierce anger of the Lord may turn away from Israel.” Here endeth the first lesson. Let us now sing Hymn five hundred and eighty seven, All Things Bright and Beatuiful.

God, however, has not finished with the Baal of Peor and those who worship it. But whereas in these first verses he had commanded Moses and the Judges of Israel to string some of his own chosen people up in the sun, the next episode describes an independent action taken by someone who knows His divine anger, knows His wishes, and does not need a direct command nor any official permission or sanction to act on that knowledge:

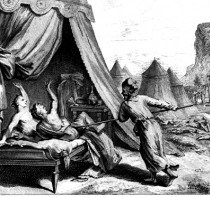

And behold, one of the people of Israel came and brought a Midianite woman to his family, in the sight of Moses and in the sight of the whole congregation of the people of Israel, while they were weeping at the door of the tent of meeting. When Phinehas the son of Eleazar, son of Aaron the priest, saw it, he rose and left the congregation, and took a spear in his hand and went after the man of Israel into the inner room, and pierced both of them, the man of Israel and the woman, through her body. Thus the plague was stayed from the people of Israel. Nevertheless those that died by the plague were twenty-four thousand.

That’s a fairly graphic description of a double murder, particularly when one considers that the phrase “pierced both of them, the man of Israel and the woman, through her body” is generally taken to mean that Phinehas caught the pair of them in flagrante and speared them through their conjoined offending parts.

God, who according to other passages in scripture is Love, is distinctly pleased by this turn of events:

And the Lord said to Moses, “Phinehas the son of Eleazar, son of Aaron the priest, has turned back my wrath from the people of Israel, in that he was jealous with my jealousy among them, so that I did not consume the people of Israel in my jealousy. Therefore say, `Behold, I give to him my covenant of peace; and it shall be to him, and to his descendants after him, the covenant of a perpetual priesthood, because he was jealous for his God, and made atonement for the people of Israel.”

Killing is killing, however, and it is only fitting that we should know the names of the victims. Our text continues:

The name of the slain man of Israel, who was slain with the Midianite woman, was Zimri the son of Salu, head of a fathers’ house belonging to the Simeonites. And the name of the Midianite woman who was slain was Cozbi the daughter of Zur, who was the head of the people of a fathers’ house in Midian.

Cozbi and Zimri: their names have not perished from memory.

And the Lord said to Moses, “Harass the Midianites, and smite them; for they have harassed you with their wiles, with which they beguiled you in the matter of Peor, and in the matter of Cozbi, the daughter of the prince of Midian, their sister, who was slain on the day of the plague on account of Peor.”

From a counter-terrorist perspective, this is the incipit — chapter one in the still unfolding history of religio-political violence, and our first instance of the “lone wolf” operative.

III

As Steven Bayme of the American Jewish Committee notes in his article, Extremism and Zealotry: The Case of Pinchas, the story certainly appears to offer some sanction for religious violence.

At initial glance, this text appears to validate extremist ideology and behavior. An Israelite male and a Midianite female are engaged in publicly lewd behavior. God is angry and sends a plague. Moses appears to be incapacitated, possibly on account to his own marriage to a Midianite woman. So Aaron’s grandson, Pinchas, decides to act on his own, grabs a spear, kills the offending couple, and the plague is stopped. Subsequently, God confers his “covenant of peace” upon Pinchas as a reward for his “zealotry.” Latter-day zealots in fact have modeled themselves upon the case of Pinchas.

In writing these posts, I take the story of Phineas as emblematic of all the apparent sanctions for religious violence (the “landmines in the garden” of my title) buried in the world’s scriptures, rituals, histories and hagiographies. But the issue is not restricted to Judaism alone, or Judaism and Christianity, or indeed the three Abrahamic religions. Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita gives sanction to Arjuna‘s battlefield violence, and even Buddhism has a prophecy of a righteous war between the Buddhists and Islam in the very same Kalachakra Tantra that HH the Dalai Lama teaches — though in that case, the violence is envisioned as taking place centuries hence.

IV

Perhaps not surprisingly, given its place within the scriptures of two great religions, this story of Phineas, Cozbi and Zimri echoes down the centuries.

It is first retold in Psalm 106, and again, I probably sang these words to the glorious four-part harmonies of the English choral tradition (at the 6.27 mark in this Guildford Cathedral rendition) in my childhood:

Then stood up Phinees and prayed * and so the plague ceased.

And that was counted unto him for righteousness * among all posterities for evermore.

This might seem to add nothing to the account in Numbers, but in fact a subtle shift is already taking place. As Bayme puts it, the Psalmist “quietly transformed the word for Pinchas’s zeal into one connoting prayer.”

It is often the case that the normative teachings of a great religion strongly promote peace and are at pains to offer alternative interpretations of such passages as the Phineas story, while individuals or extreme groups within them still refer to these “landmine” passages for religious sanction.

**

In the next section of this post I shall follow the trail of Phineas / Pinchas through the deutero-canonical Books of the Maccabees, in New Testamental, Talmudic and Patristic writings, and perhaps up through Milton and Brigham Young.

A final post will deal with Hoskin‘s book Vigilantes of Christendom, its tie in with Louis Beam‘s theory of “leaderless resistance” and related events of the last half-century or so — and the happily failed attempt at a massacre in Austin these last few days.

I have a lot of work before me, as well as much already written: I look forward to your pointers, corrections and support.

December 19th, 2014 at 8:47 am

“Thinking back on my time as a choir-boy, I imagine those sonorous phrases about the anger of the Lord, delivered in the splendid prose of the King James Version, must have rolled right over me, …”

.

Charles, did you never hear “The Lord Is a Man of War,” the magnificent duet for two bases from Handel’s “Israel in Egypt,” 1739, HWV 54, sung as an anthem at evensong early in February?

.

.

(The Lord is a man of war: Lord is His name. Pharaoh’s chariots and his host hath He cast into the sea; his chosen captains also are drowned in the Red Sea.

Exodus xv: 3, 4)

December 19th, 2014 at 4:06 pm

Thank you, Michael.

.

My associations with “a man of war” back then would probably have been naval in nature, I suspoect:

.

.

Much the same as Dreadnaught — which is what the angels say to mortals they wish to contact, isn’t it?

.

But to my later chagrin, I’m afraid I never took much advantage of the Christ Church choir while I was up at Oxford — foolish to have been in a House with so much fine music, while hardly ever partaking.

.

Thanks again.