“I work for crazy too.”, Here Clausewitz explains: Part II: Hu’s on first?

Let’s go back to June 5, 1989, to Peking, to this very spot. On arrival, recovering from a bad case of time lag, we notice Clausewitz’s disembodied floating head circling the scene. No one else see’s the Clausewitz head. A sensible disembodied floating head, the Clausewitz head has selectively cloaked itself in invisibility so it doesn’t draw the fire of the People’s Liberation Army, who were, understandably, jittery that day. Seeing the disembodied floating head of a long dead and much reviled Prussian military theorist is the sort of thing that would make a jumpy PLA peasant conscript fire indiscriminately into the middle of a major city. His superiors wouldn’t be amused. People’s Liberation Ammunition is supposed to be expended on unarmed civilians, not gwailo disembodied floating heads. The debriefing of this particular tank crew would be tense. Their final defense may come down to Marx, Lenin, and Mao’s favorable citations of the original bearer of this particular disembodied floating head.

Whether Tank Man would flee if he too could see the Clausewitz head is unknowable. Our only clue is Tank Man’s demonstrated courage in choosing to stand in front of a column of Type 59 tanks without the immediate assistance of his very own M-1A2 Abrams tank. If he could see the Clausewitz head, he might realize that, since he is neither a simpering Basil Liddell Hart, a sinister kitten-hating Martin Van Creveld, or some other purveyor of snake oil, he has nothing to fear from the Clausewitz head. In any event, none of the other participants in this historical vignette can see the Clausewitz head.

However, due to the power of IPv6, we can see the Clausewitz head. The events that we and the invisible disembodied floating Clausewitz head witness are known history:

The [Tank Man] incident took place near Tiananmen on Chang’an Avenue, which runs east-west along the south end of the Forbidden City, [Peking], on June 5, 1989, one day after the Chinese government’s violent crackdown on the Tiananmen protests. [Tank Man] placed himself alone in the middle of the street as the tanks approached, directly in the path of the armored vehicles. He held two shopping bags, one in each hand. As the tanks came to a stop, [Tank Man] gestured towards the tanks with his bags. In response, the lead tank attempted to drive around the man, but the man repeatedly stepped into the path of the tank in a show of nonviolent action. After repeatedly attempting to go around rather than crush the man, the lead tank stopped its engines, and the armored vehicles behind it seemed to follow suit. There was a pause for a short period of time with the man and the tanks having reached a quiet, still impasse.

Having now successfully brought the column to a halt, [Tank Man] climbed up onto the hull of the buttoned-up lead tank and, after briefly stopping at the driver’s hatch, appeared in video footage of the incident to start calling into various ports in the tank’s turret. He then climbed atop the turret and seemed to have a short conversation with a crew member at the gunner’s hatch. After ending the conversation, [Tank Man] alighted from the tank. The tank commander briefly emerged from his hatch, and the tanks restarted their engines, ready to continue on. At that point, [Tank Man], who was still standing within a meter or two of the side of the lead tank, leapt in front of the vehicle once again and quickly reestablished the [Tank Man]-tank standoff. Video footage shows that two figures in blue attire then pulled the man away and absorbed him into the crowd; the tanks continued on their way.

The reason we’ve returned to this place and time is to ask the Clausewitz head whether this scene we are witnessing is consistent with his well-known observation that, “War is the continuation of political intercourse with the addition of other means.” The Clausewitz head may deign to speak to us. It may remain tactfully silent. It may merely nod its assent by inclining forward, perhaps even rotating vertically 360 degrees.

Freaky.

It may choose to shake its head in profound disapproval, perhaps so emphatically that it rotates horizontally 360 degrees.

Even freakier.

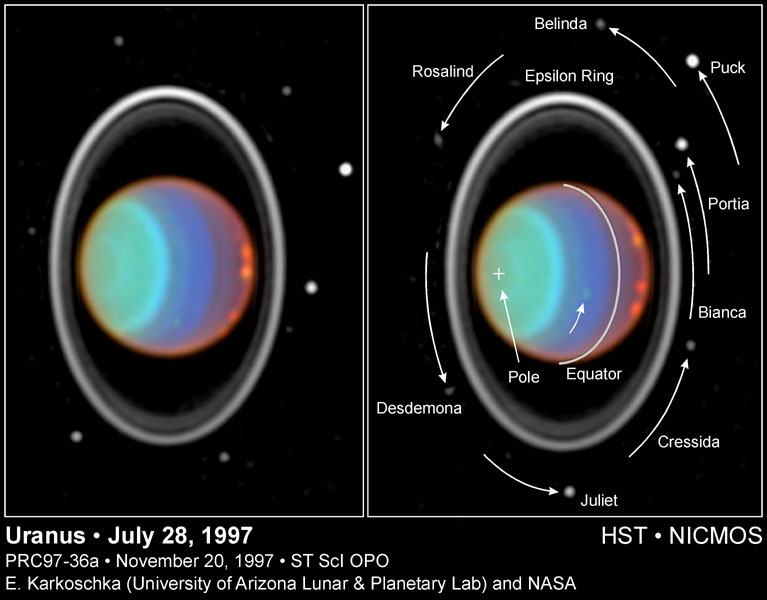

For purpose of argument: we’ll channel the Clausewitz head here: its answer is yes. In fact, the Clausewitz head is in such total agreement with our question that it is currently rotating on its horizontal axis like the disembodied floating planet Uranus.

Clausewitz Agrees

How is it that both Tank Man and a PLA tank column find themselves in agreement with a foreign devil disembodied floating head’s most famous catchphrase? This unwitting agreement with the mighty Clausewitzian head unfolds on many levels, transcending the particular time, place, and participants of Tank Man’s moment. Some of this agreement is the direct result of what happened on that street, with those people, with those armored vehicles, and with those shopping bags. Some of this agreement is what others have made and will make of what happened on that street, with those people, with those armored vehicles, and with those shopping bags.

Clausewitz’s absolute war, though an abstraction, is a very aggressive abstraction. If it suddenly manifested itself manifested in this particular tank column, Tank Man is gone. Barely discernible thump: no more Tank Man. The only annoyance Tank Man would cause the People’s Liberation Army is the effort of cleaning him out of the tank treads. But then scraping unarmed civilians out of tank treads is what peasant conscripts are for. Not only that, there are a lot of tanks in that column.

M Tanks

Even if you replaced Tank Man with Mr. T, that’s a lot of tanks for one shopper to take out.

Here is where real war replaces absolute war. The factor that differentiates the two is politics, acting as a ratchet to scale real war back from hypothetical extremes of absolute war. While, in purely military terms, Tank Man is hopelessly outmatched, on the political level the tanks are hopelessly outgunned. Tank Man has the advantage. He has that entire column of tanks trapped in a political gray zone. Tank Man seems to have been returning home from shopping when, suddenly, he decided to stand in front of a column of tanks. It was an unintentional moral ambush: Tank Man surprised the lead tank driver. He may have surprised himself.

To the lead tank driver, Tank Man is supposed to be smart enough not to stand in front of a column of tanks. Heck, everyone is supposed to be smart enough not to stand in front of a column of tanks. Yet there he is.

And Tank Man is alone. If you’re going to insist on standing in front of a column of tanks, you should probably try to find a few others who’d be crazy enough to stand in front of a column of tanks with you. However, if Tank Man was with others or Tank Man was trying to throw a Molotov Cocktail at the lead tank, the tanks have a prepared response. But nothing in their training or orders seems to have prepared them for facing a lone Tank Man. There may not be an entry in the PLA tank operating manual that says, “Turn to page 114-B for instructions for dealing with lone Tank Men blocking your way. Refer to diagram.”

While it may be politically opportune for the security forces of the Red China to massacre many students in the middle of the night, running over a lone Tank Man in the middle of the day might not be. Tank Man’s action is a clearly political action, one that even a random tank crew can recognize as opposing, in its own small way, the Chinese Communist Party. In its own small way, it’s an act of war, expressing hostile intent against the political position of the current ruling clique. But the lead tank’s crew lacks an appropriate political response.

Amidst the Ruins

Tank Man may have accidentally exposed a political seam between the jurisdiction of the PLA and the jurisdiction of the Chinese internal security forces. Dealing with the many in the middle of the night is something the PLA had orders for. Dealing with the one in the middle of the day may not have been. This is probably a situation the PLA would usually leave to line internal security forces. The tank crews may have even been briefed that there were foreign devils in the vicinity, especially foreign devil media, making any sudden running over of Tank Men bad politics. The logical conclusion, especially in a top down organization with a poor track record of rewarding personal initiative in subordinates, is to sit still and radio for instructions.

This allowed Tank Man to launch his one man propaganda war, climbing the tank and assaulting its crew with messages contrary to the general political thrust of their orders. The PBS Frontline documentary The Tank Man relates how many protesters and their sympathizers would beg the police and army not to attack their fellow subjects. In some ways this desperate tactic of moral suasion was initially successful. This initial success may have worried the Chinese Communist Party leadership. Many PLA units later brought into Peking were drawn from peasants from the countryside who were not necessarily simpatico with city dwellers. This lack of simpatico allowed the PLA to mow down protesters with little evident protest from PLA soldiers doing the mowing. The regional identity of this particular tank crew and their individual political opinions are unknown. Whatever their place of origin, in this place they stopped and waited.

The face off was resolved when someone dragged off Tank Man and his groceries. Opinions about who it was that dragged him off differ. Some witnesses believe it was friends of Tank Man, saving him from his headbutting with history. Others believe it was secret police who dragged him off, perhaps summoned by the lead tank crew or other snitches. Nothing more is known about Tank Man or who he was. Nothing is known about his fate. He may have been arrested and later shot. He may have gone underground. He may have simply returned to the anonymity from which he temporarily sprang.

His fate doesn’t change the immediate outcome of the event. It was a stalemate and, as with most of such stalemates, the tank column won. Only if Tank Man had inspired that entire tank column to turn around and head for Jungnanhai, possibly accompanied by a crowd that spontaneously broke into song and dance, would he have won the face off. Perhaps if Tank Man had been a Chinese Mr. T, one of those magical flying Shaolin monks that died by the millions fighting Pei Mei, or the dread Manchu. Tank Man would be just more forgotten Tank Man grist for the Communist tyranny mill if not for happenstance. The presence of foreign media who took video and photos of the face off transformed Tank Man into a cultural archetype, a warrior of story.

Tank Man’s story, his own private compression of the outside world, is lost to the world. His story only survives as the messages it unintentionally sent. If a story is a compressed version of the outside world, a message is a compressed version of a story. If stories are compressed by throwing out large parts of the immensity of the outside world they embed, messages are compressed by throwing out large parts of a story they embed. Messages are the pale shadow of a pale shadow. Yet messages are how stories spread. Only by tighter compression can stories be communicated through the narrow limits of language. No other human to human medium available to mortal man offers a similar level of throughput.

Tank Man sent messages directly to the tank column. Blocking the column was a message. Climbing on the tank, propagandizing the crew, that was a message. Yet those messages were lost. Tank Man’s message to the world outside his moment is entirely indirect and inferred. Whatever Tank Man communicates to us is entirely through messages transmitted through other people, mostly foreign devils complete with long noses and flaming red hair.

Say Tank Man was convinced that shopping bags bestowed immunity to Soviet-style tanks. Say he was an expert on Type 59 tanks and he wanted to demonstrate just how feeble they were. Say he was an agent provocateur of the Communist Party, sent out to test the loyalty of random PLA tank crews. We’d never know. Foreign journalists saw what they saw and compressed it according to their own cultural compression mechanisms.

Tank Man’s message, whatever it was originally, has become a message of resistance to Communist oppression. This is the message that the Chinese government fears enough that it is blocked by the Great Firewall of China, along with all references to the Tiananmen Incident. Tank Man’s message is now hopelessly mixed with other potent messages that have been invading China since the First Opium War. The relative helplessness of China against the West and Russia was a deep shock to the predominant Chinese cultural story, shaking it its foundations. Its aftershocks linger to this day. This shock intensified after the First Opium War with the Taiping Rebellion, a strange hybrid of traditional Chinese culture and Christianity unwittingly unleashed by an American missionary, that lasted for 14 years and left around 20 million dead. The later nineteenth century brought more foreign narratives to China as European powers, Russia, and even the Japanese carved out enclaves. Missionaries, especially, it seems, American missionaries, infected the Chinese with all sorts of strange messages. With the fall of the Manchu Dynasty, this infection metastasized. Marxism, Fascism, democracy, and other ideas came through. Marxism, heavily adapted to Chinese sensibilities by Mau, triumphed for a while, only to fall before the awesome onslaught of Alexander Hamilton and the American System transmitted by Lee Kwan Yew and Friedrich List.

This is where Red China gets nervous. Culture is the division of priority between stories. Priority is achieved through politics, the division of power between stories. There is a self-reinforcing relationship between culture and politics. Culture tends to favor politics that reinforces its dominant storylines. But it’s a two-way street. Politics tends to favor cultural stories that favor dominant holders of power. Successful culture tends to generate successful politics. Successful politics tends to reinforce successful culture. The opposite is also true: unsuccessful culture tends to generate unsuccessful politics and unsuccessful politics tends to lead to unsuccessful culture. If you’re riding a cultural wave, there’s always the chance that things will suddenly go wrong. Cultural challenges are the most potent challenges. They can knock the foundation out from beneath the strongest seeming political power structure.

Small changes in story priority can generate massive shifts in political power. Stories are very powerful. Man is a creature of story. Spreading story through messages is something man does without much thought. Stories that, when compressed down to messages, come out vivid, visual, visceral, visionary, viral, or validating, prove to be excellent candidates for triggering changes in cultural priority. Tank Man is unusually vivid, visual, visceral, visionary, viral, and validating. Under the right circumstances, mixed with other suitable stories, Tank Man could be truly scary to Red China. Red China has fought against Tank Man in China, killing, repressing, obfuscating, blocking, bribing, and denying all the way. But Tank Man is currently beyond the reach of the Red Chinese government. It lingers over the horizon, on the Web, in magazines, on television, in foreign countries, and surreptitiously within Red China itself, forever threatening.

Tank Man is waging war on China’s current regime, with the ultimate aim of achieving a different political result where the division of power is shifted to other stories than Marxist-Hamiltonianism. The original incident was triggered by the politically motivated act of stepping in front of a tank column. The incident was allowed for a time by a politically motivated stop by the lead tank crew. The message of the original incident was captured by politically motivated journalists. It has been taken up by politically motivated opponents of the regime and used as a weapon of war against it. This war is a continuation of the political intercourse between the regime and its opponents. The crazy act of stepping in front of a tank is an inherently Clausewitzian act and as guaranteed as anything to draw the attention and approval of the disembodied floating Clausewitz head.

The ultimate outcome of the battle between Tank Man and competing messages is up in the air. Consider the story gap to be closed:

Obama: I got my job because I have a remarkable talent for reading a teleprompter.

Hu: Interesting. I got my job because I have a remarkable talent for killing Tibetans.

June 6th, 2015 at 2:15 pm

Bravo.

June 7th, 2015 at 3:25 am

“Say Tank Man was convinced that shopping bags bestowed immunity to Soviet-style tanks.”

The Tank Man also convinced Fukuyama and Pinker and others that Shopping Bag Diplomacy was the solution to history.