Sunday surprise: three entangled faiths

[ by Charles Cameron — two exhibits linking the Abrahamic faiths ]

.

For disciplinary as well as doctrinal purposes, the three Abrahamic faiths — Judaism, Christianity, Islam — are generally thought of separately — a separation which the two exhibitions this post revolves around are intended to bring into question.

**

One: Of gods and men: how Egypt was a crucible for multiple faiths

For instance, there’s a “stele of Abraham” in the British Museum show from last autumn that is worth pondering:

The accompanying text tells us:

On public display for the first time will be a gravestone, or stele, for a man called Abraham. “It commemorates someone with a Jewish name and yet it bears Christian symbols inside a classical frame next to the ankh symbol, the ancient Egyptian sign of life,” said O’Connell. “What is more, the engraving on it says he was ‘the perfected monk’ and is written in Coptic Egyptian.”

More about the show:

Curators at the London museum will use a series of items, many never put on public display before, to demonstrate the level of “entanglement” of religious symbols and rituals; with Egyptian emblems regularly appearing in classical Greek designs, depicting Jewish stories that were decorated with Christian crosses and Roman wreaths.

“Over the last 10 or 15 years in scholarship, there has been growing interest across the disciplines in looking at the way religions interacted, rather than just in isolation,” said Elisabeth O’Connell, a keeper in the museum’s Department of Ancient Egypt and the Sudan and a co-curator of the exhibition. “It is becoming clear that a lot of religious history has been founded on our modern distinctions simply being projected back.”

Note in the next paragraph the use of the terms ” troublesome” and subversive”:

Two hundred of these troublesome objects, many deliberately ignored by scholars in the past, have been gathered together to challenge the conventions of religious history. From architectural fragments, jewellery, paintings, gravestones and toys, to the paraphernalia of religious worship, they are all subversive evidence that faiths were once amalgamated in a way that was accepted by the ordinary people of Egypt, regardless of their birth-race or family’s religion.

Those are the Guardian writer’s words — Vanessa Thorpe‘s — not the words of the curators, but it seems the exhibit is intended to emphasize the “melting pot” side of Egyptian religion across the millennium after the fall of the Pharaohs rather than the separations:

“If you only take the work we have from Dioscorus of Aphrodito, it blows apart these distinctions,” said O’Connell. “He was a lawyer and poet, who lived in Egypt and wrote in Greek, although he was a Christian Copt.

“He is a great example of what was going on widely, because he used biblical sources and also wrote Homeric verse, one of them dedicated to a man with a Christian name, Matthew.”

**

Much the same impulse appears to have been behind a British Library exhibit in 2007:

Two: Sacred texts that reveal a common heritage

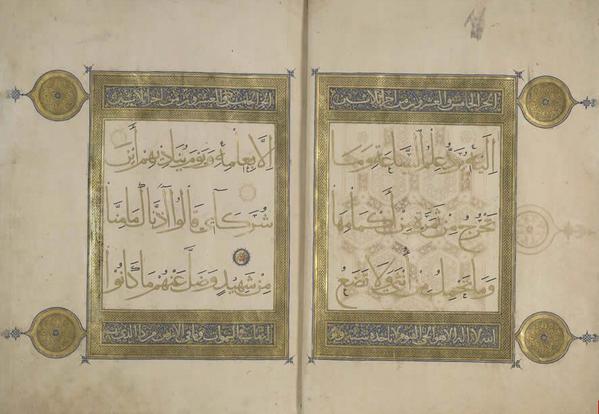

For the first time, the oldest and most precious surviving texts of the Jewish, Christian and Islamic faiths have gone on display side by side at the British Library. They include a tattered scrap of a Dead Sea Scroll and a Qur’an commissioned for a 14th-century Mongol ruler of modern Iran who was born a shaman, baptised a Christian, and converted first to Buddhism, then Sunni and finally Shia Islam.

Here’s a two-page spread of that “Mosul Qur’an“:

reduced image via the British Library

The Guardian article continues:

The exhibition also has some exotic private loans, including an embroidered 19th-century curtain which once covered the door of the Ka’bah, the shrine which is at the core of the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, a hand embroidered Jewish bridal canopy – and a gold shalwar kameez worn by Jemima Goldsmith in 1995, when she married the former Pakistan cricket captain Imran Khan.

Phew, pop-cultural enthusiasts will at least have had the shalwar kameez to give them comfort!

More:

Graham Shaw, the lead curator, said: “We were determined not to create faith zones, but to show these wonderful manuscripts side by side, and demonstrate how much we share – not least that these are three faiths founded on sacred texts, books of revelation.” Many exhibits are among the oldest of their kind, including a Qur’an made in Arabia within a century of Muhammad’s lifetime.

The exhibition also shows how calligraphers and manuscript illuminators shared influences and styles. The microscopically detailed decorated capital letters of the Lindisfarne Gospels are echoed in Islamic and Jewish manuscripts, while Christian and Jewish texts borrowed Islamic-inspired decoration, so that a 14th century Qur’an and a translation of the gospels into Arabic are indistinguishable at a glance, and two 13th-century French texts, one Christian, one Jewish, use virtually identical images of King David.

And this part tickled my fancy, and will surely find a place in my book on Coronation and Monarchy if it ever finds a publisher:

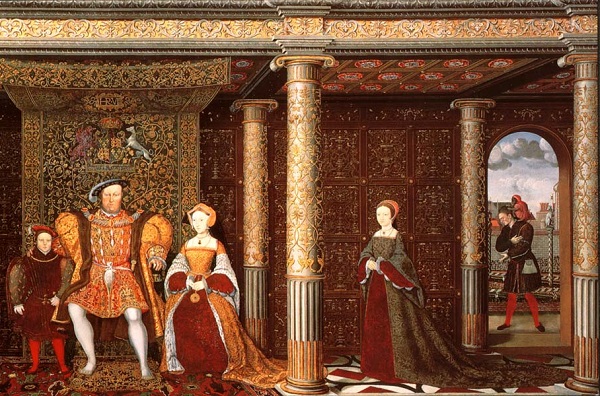

A later psalter owned by Henry VIII outrageously uses his portrait as the great Jewish king – accompanied by Henry’s court jester, William Somer, beside a text which translates as “the fool says in his heart ‘there is no God'”.

The wise fool Will Somer or Sommers wasn’t quite a member of Henry VIII’s Royal Family, but stands nearby, in the arch far right, in this detail from a family portrait of 1545 or thereabouts: