One of England’s Freedoms

[ by Charles Cameron — an amused defense of sacred measures such as the foot, yard, and acre — against the atheistic and idolatrous metric system ]

.

**

You can trudge uphill, you can run up hill and down dale as the saying goes, you may march from pillar to post, church spire to spire, you may follow ancient foot- or bridle-paths or ley lines — all these, if pursued on foot, are covered by the word rambling, and in England, if you follow well-trodden or half forgotten paths, it’s your right. It is one of England’s freedoms.

**

Sam Knight, in the New Yorker a couple of days ago, The Search for England’s Forgotten Footpaths:

Nineteen years ago, the British government passed one of its periodic laws to manage how people move through the countryside. The Countryside and Rights of Way Act created a new “right to roam” on common land, opening up three million acres of mountains and moor, heath and down, to cyclists, climbers, and dog walkers. It also set an ambitious goal: to record every public path crisscrossing England and Wales… [ .. ]

Between them, England and Wales have around a hundred and forty thousand miles of footpaths, of which around ten per cent are impassable at any time, with another ten thousand miles that are thought to have dropped off maps or otherwise misplaced. Finding them all again is like reconstructing the roots of a tree.

Now that’s all numbers, and numbers are, d’oh, quantitative. The thing is, walks in the English countryside are primarily qualitative affairs, with mud, styles to clamber across, flash thunderstorms and after-storm greenery, oaks with mistletoe or a thousand rooks high in their branches, willows, snails, birdsong, conversation with a friend or two.. Plato, Brahms, Ann Patchett, Feynmann, Hitchcock, .. with picnics and sandwiches along the way..

Freedom!

Qualitative beats quantitative all to smithereens.

**

If you look at the photo that accompanies Sam Knight‘s New Yorker piece [above], it belies the “unremarkable walk in the English countryside” mentioned in its caption — clear on the horizon is Glastonbury Tor, hardly an unremarkable location for English walkers.

Ever since my friend the late British hedgerow philosopher John Michell [above] — hedgerow and British Museum Reading Room philosopher, that is — wrote his startling best-seller The View Over Atlantis [below] —

— ever since that book appeared, new-agers and ramblers have rambled along ley lines and in search of standing stones — I was one such rambler, along with Michell himself and our mutual friend, the photographer Gabi Nasemann, though I fear I was the slowest and most complaining in our small party — where was I? — Glastonbury Tor has been a sort of seekers’ central for those whose imaginations project ley lines — equivalent to Chinese dragon-paths — across the actual lay of the land.

Another friend, Lex Neale, penned this piece, Glastonbury: King Arthur’s Field, giving an overview of Glastonbury and the supposed zodiac spread out around it —

for my then guru’s in-house magazine, lo these many years ago. By then I was in America. And we were young.

**

Why do I so love my memories of John Michell?

He was a William Blake returned, wrong by the mechanical standards of the age, right in imaginative reach.

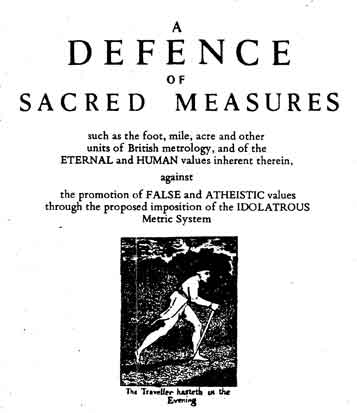

It was in the Spring 1978 issue of CoEvolution Quarterly that I first read the text of John‘s A Defence of Sacred Measures. He’d published it as a pamphlet — the first in a series of “Radical Traditionalist Papers” to which our mutual friend the recently deceased Heathcote Willians also contributed — Heathcote {below] —

do watch this clip, it’ll only take three minutes of your lifetime, and they’ll be three minutes well-spent! —

—

— and Stewart Brand must have snagged it for CoEQ. Anyway, you can get the gist from the full title, in the format the pamphlet gave it, as you may have seen at the head of this post:

I’m deeply grateful to Zenpundit friend Grurray for pointing me to that cover and the full text of John‘s essay, which my own web searching hadn’t turned up. Grurray took particular pleasure in this excerpt:

the use of the foot locates the centre of the world within each individual, and encourages him to arrange his kingdom after the best possible model, the cosmic order. The ancient method of acquiring this model was not astronomy but initiation

For myself, it’s John‘s description of the cubit and sundry other measures — and their rationale — that gets me:

Cloth is sold by the cubit, the distance from elbow to finger tip, and other such units as the span and handbreadth were formerly used which have now generally become obsolete. Of course no two people have the same bodily dimensions, and the canonical man has never existed save as an idea or archetype. These traditional units are not, however, imprecise or inaccurate. Ancient societies regarded their standards of measure as their most sacred possessions and they have been preserved with extreme accuracy from the earliest times. A craftsman soon learns to what extent the parts of his own body deviate from the conventional standard and adjusts accordingly.

**

Oh, you may think this all a pretentious, anachronistic attempt to revive a moribund system. But consider this, from the LA Times in 1999:

NASA lost its $125-million Mars Climate Orbiter because spacecraft engineers failed to convert from English to metric measurements when exchanging vital data before the craft was launched, space agency officials said Thursday.

A navigation team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory used the metric system of millimeters and meters in its calculations, while Lockheed Martin Astronautics in Denver, which designed and built the spacecraft, provided crucial acceleration data in the English system of inches, feet and pounds.

As a result, JPL engineers mistook acceleration readings measured in English units of pound-seconds for a metric measure of force called newton-seconds.

In a sense, the spacecraft was lost in translation.

The Times assumes the correct procedure would have been “to convert from English to metric measurements” — but who says? One might equally argue the translation should have gone from metric to English.. the mother tongue, so to speak.

John Michell would lead us along that path..