Yiddish humor, US Presidential Election

Friday, August 24th, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — Jewish Democrats suggest humorous barbs for Jewish Republicans to digest ]

.

As those who follow my strand of posts her on Zenpundit know by now, I’m not a great one for taking sides: I imagine very few bridge builders are, and my real interest is in building bridges.

I am also, in general, interested in the ephemeral signals that go on between and within opposing camps — because they’ll often portray a different side of things from what’s in the official pronouncements.

What I’m offering here, then, is a fleeting glimpse into some Jewish humor from the Democratic side of things:

.

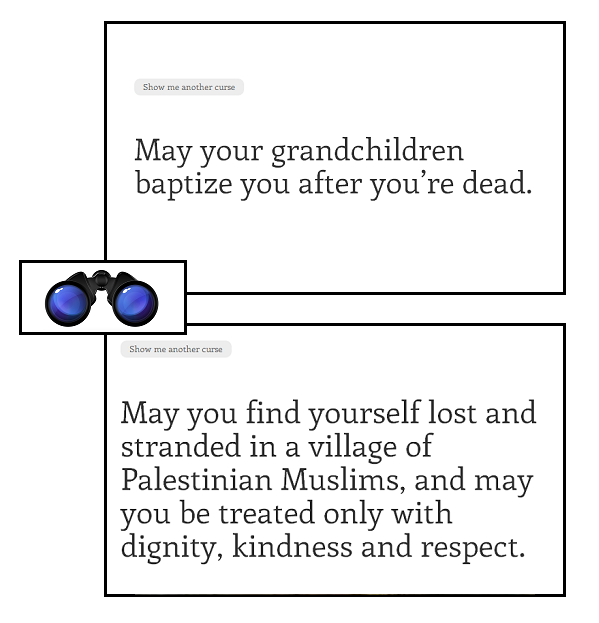

— two “curses” from the from the Yiddish Curses for Republican Jews website.

As wry humor, I’m okay with these. As embittered humor, not so much.

And I don’t know the people who posted these “curses” — though I’m reasonably sure they didn’t intend them as actual, may G*d do this to you and I mean it, curses.

Frankly, I’m interested in the religious content.

**

I’m interested in the jokes.

I’m interested in the leaflets, the comments in the comment sections of websites — and in the winks, the nudges and the nods.

I’m interested in the differences between “in-house” and “external” explanations of things, what the differences may actually mean, and what they may get interpreted to mean. I’m interested in the asides, the sneers and smears, the jokes, the ambiguous threats, the real hatreds, the moments of reflection, the metanoias, changes of heart, repentances.

At times, the materials I run across are threatening, at times witty or droll, at times insightful, and at times completely unhinged from reality, but they usually have something to teach us about undercurrents — about the variousness of human thoughts and feelings.

We humans are a strange lot, each one of us so singular that we have a hard time getting our heads around the differences between us — differences that can make all the difference between peace and war, life and death.

**

I’m not going to explain the jokes, but I am going to take just a quick look at their religious content.

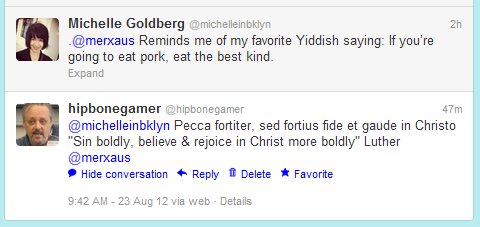

One of the qualities that is, IMO, most likeable about Jewish culture is that it delights in self-mockery. The New York Times journalist Michelle Goldberg tweeted a Jewish joke yesterday, to which I responded with a quote from Martin Luther:

Now I don’t know about Michelle, but I didn’t intend my quote from Luther — “sin boldly” — as representing either my personal advice to the world at large, or Luther’s, except perhaps in a very limited sense such as the one Dietrich Bonhoeffer offered as his explanation of Luther’s meaning.

Bonhoeffer’s question is the obvious one:

Is this the proclamation of cheap grace, naked and unashamed, the carte blanche for sin, the end of all discipleship? Is this a blasphemous encouragement to sin boldly and rely on grace? Is there a more diabolical abuse of grace than to sin and rely on the grace which God has given?

And his response?

Take courage and confess your sin, says Luther, do no try to run away from it, but believe more boldly still. You are a sinner, so be a sinner, and don’t try to become what you are not. Yes, and become a sinner again and again every day, and be bold about it. But to whom can such words be addressed, except to those who from the bottom of their hearts make a daily renunciation of sin and of every barrier which hinders them from following Christ, but who nevertheless are troubled by their daily faithlessness of sin? Who can hear these words without endangering his faith but he who hears their consolation as a renewed summons to follow Christ? Interpreted in this way, these words of Luther become a testimony to the costliness of grace, the only genuine kind of grace there is.

**

So no, I don’t think all religiously-themed tweeting and web-based cursing is to be taken literally.

But I do find it interesting that Michelle jokes about kosher, and I joke about sinning boldly — and that the Yiddish humor displayed on the “curses” website includes references to the LDS practice of proxy baptism for the dead and an indication that it might be uncomfortable for those with strong anti-Muslim feelings to meet the generous hospitality that so often characterizes Muslim cultures.

So let’s dig into those two themes in a little more depth.

**

Official Latter-day Saints doctrine teaches:

Jesus Christ taught that baptism is essential to the salvation of all who have lived on earth (see John 3:5). Many people, however, have died without being baptized. Others were baptized without proper authority. Because God is merciful, He has prepared a way for all people to receive the blessings of baptism. By performing proxy baptisms in behalf of those who have died, Church members offer these blessings to deceased ancestors. Individuals can then choose to accept or reject what has been done in their behalf.

And while the practice of baptizing the dead by proxy may seem strange to most Christians, the Latter-day Saints can point to I Corinthians 15.29:

Else what shall they do which are baptized for the dead, if the dead rise not at all? why are they then baptized for the dead?

and I Peter 4.6 for precedent:

For for this cause was the gospel preached also to them that are dead, that they might be judged according to men in the flesh, but live according to God in the spirit.

Maybe so — but Saints Peter and Paul, though Jewish by birth, are now generally reckoned Christians, having accepted the belief that Jesus was the awaited Jewish Messiah, the Christ — so their epistles are not canonical texts for mainstream Judaism.

**

Feelings in the Jewish community can run pretty strongly on the issue of Mormon believers’ baptisms of Jewish believing dead:

The wrongful baptism of Jewish dead, which disparages the memory of a deceased person is a brazen act which will obscure the historical record for future generations. It has been bitterly opposed by many Jews for a number of years. Others say they will never stop being Jews, simply because there is a paper saying they had been baptized, that the act of posthumous baptism is unimportant and should be ignored. We think this to be a narrow, parochial, and shallow view. We will continue opposing this wrongful act which assimilates our dead to the point where it will not be possible to know who was Jewish in their lifetimes.

[ … ]

A protest drive initiated by Jewish genealogists escalated it to a nationally publicized issue that was followed by public outcry. American Jewish leaders considered it an insult and a major setback for interfaith relations. They initiated discussions with the Mormon Church that culminated in a voluntary 1995 agreement by the Church to remove the inappropriate names. Activists continue to monitor Mormon baptismal lists, seeking removal of inappropriate entries.

Indeed, in February of this year it was discovered that the Holocaust victim Anne Frank had been baptized by proxy — for what one researcher said was the ninth time.

The Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel responded with passionate anger, and the Mormon Church with an apolpogy and a firm statement that the practice was prohibited.

LDS spokesman Michael Purdy made it clear that the Church “is absolutely firm in its commitment to not accept the names of Holocaust victims for proxy baptism.”

There are serious issues here: as humans, we can listen to one another with respect, and work them out.

**

Palestinian Muslim hospitality towards Jews?

Miftah is an Ethiopian who visited some Palestinian shepherds in company with people sympathetic to the Palestinian cause:T

he group I went with was a mostly Israeli – international activists’ group that accompanies shepherds in the village as they graze their herds. Since these shepherds face attacks from settlers and soldiers frequently, the purpose of the trip was to document and confront the settlers or soldiers if they try to harass the shepherds.

These were people the Palestinians had reason to respect, Israelis and foreign activists sympathetic to their cause — but the degree of hospitality they were shown nicely illustrates the innate courtesy of so many pastoral peoples…

As we were heading back from the hills to where our mini-van was, these shepherds we had met offered to take us home for some tea and coffee. Mind you, it’s the Ramadan fasting season and all of them were fasting. They would offer us water, coffee and bread even though the last meal they had was at dawn that morning and would not have any food or water until dusk that evening. In Ramadan, even people who don’t fast don’t eat in public or in front of people who fast. But out of true hospitality, they extended their “‘Mitzvah’ – their act of kindness” to us, as one of the Israeli activists put it

**

The story is an old one: the person of few possessions who will kill one of their handful of sheep to feed the passing stranger…

In this second “curse” we glimpse the long tradition of hospitality to strangers without which the great trade routes of the ancient would would not have permitted China to supply Europe with silks, nor Roman jewelry to have found its way into Japanese tombs…