The third greatest story ever told

Saturday, January 31st, 2015[by Lynn C. Rees]

Colleen McCullough is dead (props Razib Khan).

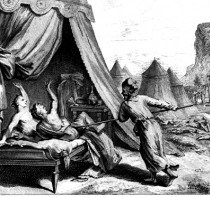

It’s a sign of George Lucas’ complete incompetence as a storyteller that he found the third greatest story ever told and left it an abomination. It is a sign of McCullough’s greatness as a storyteller that she took the third greatest story ever told and lifted it far enough to almost glimpse the second greatest story ever told. When I see the fall of the Roman Republic, I see it through McCullough’s eyes.

McCullough wrote seven books in her Masters of Rome series:

- The First Man in Rome

- The Grass Crown

- Fortune’s Favorites

- Caesar’s Women

- Caesar: Let the Dice Fly

- The October Horse

- Antony and Cleopatra

I’ve read the first six.

McCullough is given one of the greatest cast of characters in history and brings them to life:

- Gaius Marius

- Lucius Cornelius Sulla

- Mithridates VI

- Gnaeus Pompeius

- Marcus Tullius Cicero

- Marcus Licinius Crassus

- Gaius Julius Caesar

- Marcus Porcius Cato

- Spartacus

- Marcus Antonius

- Cleopatra VII Philopator

- Marcus Junius Brutus

- Gaius Cassius Longinus

- Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus

- Livia Drusilla

Lesser-known characters given their due:

- Gaius Julius Caesar – Marius’ father-in-law, grandfather of the Gaius Julius Caesar

- Julia Caesaris – her marriage to Marius resuscitates Marius’ career

- Jugurtha – king of Numidia, enemy of Rome, his capture makes Marius and Sulla

- Marcus Aemilius Scaurus – primus inter pares of the Senate, he checks Marius’ power

- Marcus Livius Drusus – conservative turned radical political reformer

- Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius – whiner, enemy of Marius, friend of Sulla, a plodder who unexpectedly turns out to be a better-than-expected general

- Quintus Servilius Caepio – jerk, steals Gold of Tolosa, gets a Roman army destroyed

- Lucius Licinius Lucullus – Sulla’s key lieutenant, party animal

- Gnaeus Pompeius – “vilest man alive”, nicknamed the “butcher”, his son was known as the “baby butcher”

- Aurelia Cotta – Caesar’s mother

- Servilia Caepionis – influential Roman politician

- Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus – he lives to frustrate Caesar

- Publius Clodius Pulcher – chronic disturber of the peace

- Vercingetorix – Gallic nobleman who plots to become king of Gaul

- Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa – Caesar Octavianus’ BFF and military right hand man

One aspect of history that McCullough’s novelizations allow her to highlight how interconnected these characters were, especially by blood ties. Genealogy helped and hindered the lives of prominent Romans in ways history books sometimes fail to capture. Servilia Caepionis, for example, was Caepio’s daughter, Drusus’ niece, Cato’s half-sister, Brutus’ mother, and Cassius and Lepidus‘ mother-in-law as well as Caesar’s long-time mistress.

McCullough uses fictional but plausible plot devices, arrived at through meticulous research, to plug gaps in the historical record. She marries Sulla to an invented short lived younger sister of Julia Caeseris, making Sulla Marius’ brother-in-law and providing a rationale for why Sulla was on Marius’ staff in Numidia. She explains Caesar Octavianus’ chronic absence from the field of battle by making him asthmatic.

Vivid scenes I recall:

- Marius, deep in Asia Minor, unarmed and alone, giving Mithridates and his army the stare down and forcing Mithridates to retreat (“O King, either strive to be stronger than Rome, or do her bidding without a word.”, according to Plutarch).

- The pompous young Pompeius, looking forward to meeting the great general Sulla on his return from the east, is shocked when the formerly handsome Sulla, disfigured by a disease (of McCullough’s invention), having lost his hair and teeth, wearing a ridiculous Raggedy Andy wig, drunkenly greets him like an sentimental old fool.

- Sulla, wandering in this ridiculous over the top getup through the streets of Rome later, then he promptly proscribes the enemies he has been sniffing out as an innocuous circus act.

McCullough’s star though out is clearly Caesar, growing from a young boy learning at the knee of Uncle Marius, to the devoted husband of the daughter of one of Sulla’s archenemies who refuses to divorce her despite Sulla going into full beast mode to the rising politician to conquering general to assassinated dictator.

Sulla, however, is her most unforgettable character. A Cornelii, one of the great patrician families of Rome, but born into a branch fallen on hard times, Sulla hangs out with the low life hipsters of Rome, uses his good looks and charm to first win the love of two rich women (who he promptly murders), and then climbs his way to the leadership of Rome’s conservative aristocratic oligarchy. He is first friends and then deadly enemies of Marius. He ruthlessly culls Rome of his enemies only to give up power and go back to his partying ways. Her Sulla makes Caesar and Octavianus look like helpless babes.

Come for Caesar, Pompeius, Cleopatra, Octavianus, or Antonius. Stay for Sulla and Marius, men overshadowed by the prima donnas they made possible. McCullough can rest in peace knowing she brought one of the primal stories of Western civilization alive for anyone who reads her books.

George Lucas can toss and turn.