April 19th anniversaries & Hegghammer’s “terrorist culture”

Sunday, April 19th, 2015[ by Charles Cameron — Thomas Hegghammer has an important new piece out, and today’s anniversaries offer an insight into why it’s important ]

.

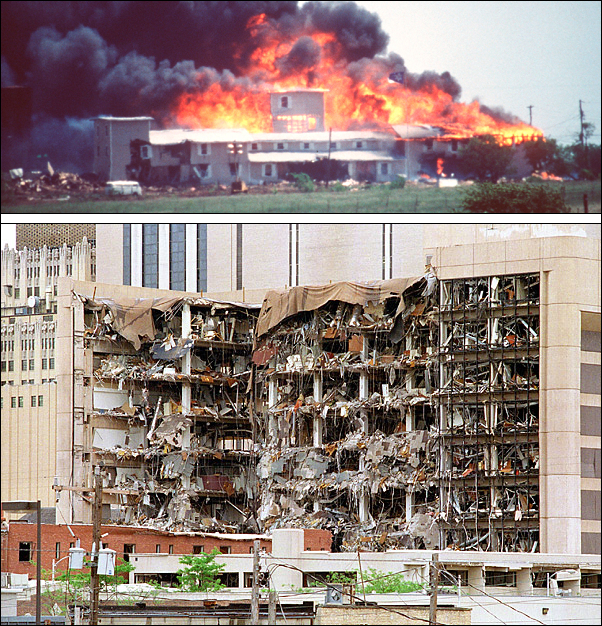

upper panel: the end of the siege of Mt Carmel, Waco, TX, 19 April 1993

lower panel: aftermath of the Oklahoma City bombing, OKC, 19 April 1995

**

The bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City took place twenty years ago today. Defense attorneys for Timothy McVeigh, who was execute for the atrocity, suggested to the court that the bombing took place on the date set for the execution of Richard Snell, who had earlier plotted to blow up the same building. From the Denver Post:

A white supremacist executed 12 hours after a bomb ripped through the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building “was the driving force” behind a plot to bomb the building 12 years earlier, according to a government memo filed by Timothy McVeigh’s lawyers.

The report was filed in U.S. District Court as McVeigh’s attorneys attempted to bolster their appeal of his conviction and death sentence with arguments that people other than McVeigh may have been involved in the bombing.

Richard Wayne Snell was mad at the Internal Revenue Service in 1983 and wanted to blow up the Oklahoma City building as revenge for IRS agents raiding his home, Fort Smith-based federal prosecutor Steven Snyder told the FBI in June 1995.

April 19 1995 was also the second anniversary of the final holocaust in the siege of the Branch Davidian compound at Waco, Texas. Mc Veigh himself told reporters Lou Michael and Dan Herbeck in a letter:

If there would not have been a Waco, I would have put down roots somewhere and not been so unsettled with the fact that my government … was a threat to me. Everything that Waco implies was on the forefront of my thoughts. That sort of guided my path for the next couple of years.

Furthermore, in their book, American Terrorist, Michael and Herbeck report:

The date he chose for the bombing was significant in two ways. Not only was it the second anniversary of the Waco raid, just as important to McVeigh, April 19, 1995, was the 220th anniversary of the Battle of Lexington and Corncord, the “shot heard ’round the world” that began the war between American patriots and their British oppressors. To McVeigh, this bombing was in the spirit of the patriots of the American Revolution, the stand of a mpodern radical patriot against an oppressive government.

**

I hope to put a post up in which I excerpt from and comment directly on Thomas Hegghammer‘s Wilkinson Memorial lecture shortly. I have been in internet hell recently, having difficulty accessing this site to edit and post, and given the date I thought it would be appropriate to post this first, however, as an example (to my mind) of what Hegghammer is talking about.

April 19 — today’s date — was triply significant to McVeigh, then, in a way that corresponds closely to Hegghammer’s definition of jihadi culture:

I define jihadi culture as products and practices that do more than fill the basic military needs of jihadi groups. This is very close to what the anthropologist Edmund Leach called “technically superfluous frills and decorations.” [ .. ]

Now think of a jihadi group. It has certain “basic needs”, such as the capacity to deploy violence and the ability to muster material resources. These needs can, conceivably, be fulfilled in a minimalist, no-frills fashion: you train, fight, raise funds, purchase weapons, write a communiqué, get some sleep, repeat the next day. To put it simply, these are the “functionally essential” elements of rebellion; everything else is culture.

The Oklahoma City bombing was held on a date that meant a great deal to Timothy McVeigh – in terms of Waco, in terms of the shot heard around the world – and on the very day of the execution of a noted white supremacist who had plotted to bomb the Murrah building, and who lived to see McVeigh destroy it shortly before he died.

Putting that another way, we can see the workings of a sort of poetic appropriateness – akin to “poetic justice” – from McVeigh’s point of view, in destroying the Murrah building on this particular day. The timing is not, in Hegghammer’s terms, “functionally essential” — it is cultural.

And what Leach called the “frills” and Hegghammer “culture” may be easily overlooked because the no-frills functional essentials seem at first glance more important –- but such things are not inessential to McVeigh, nor to Hegghammer’s jihadists who sing anasheed and write poems.

They’re essential – to the terrorists, and to our understanding of terrorism.

That’s why today is important – and Hegghammer’s lecture, likewise. I hope to return to a fuller exploration of his text as soon as my computer woes are ended.