[ by Charles Cameron — abstraction and pattern recognition as devices to evade one’s foibles, preferences, analytic assumptions ]

.

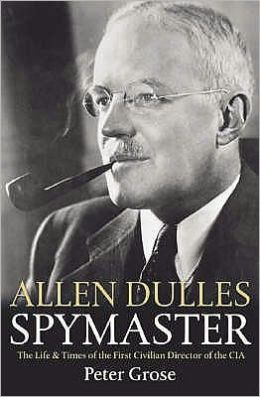

Robespierre, forensic reconstruction

**

The itaicized portion of the quote below just happens to be a concise statement of the pattern known as enantiodromia [1, 2, 3] — and the puzzlement it represents to linear (as opposed to loopish) thinkers:

Since the collapse of Jacobin rule after Robespierre’s execution in Thermidor Year II, debate has raged over how an event that began with the promise of liberty and fraternity degenerated so rapidly into fifteen months of mass imprisonment and death.

**

The quote above is from The World Turned Upside Down, a review of Jonathan Israel‘s Revolutionary Ideas: An Intellectual History of the French Revolution from the Rights of Man to Robespierre by Hugh Gough in the Dublin Review of Books. Here’s the full para:

Anyone looking for a neat explanation of the French revolutionary terror faces the problem of choice. Since the collapse of Jacobin rule after Robespierre’s execution in Thermidor Year II, debate has raged over how an event that began with the promise of liberty and fraternity degenerated so rapidly into fifteen months of mass imprisonment and death. During 1793 and 1794 around three hundred thousand people were jailed, many of them dying from disease and neglect, a further seventeen thousand were guillotined or shot and a quarter of a million killed in civil wars, of which the Vendée was by far the most deadly. After Thermidor the revolution’s opponents argued that terror on such a scale was inherent in the entire revolutionary project from the outset, part of a “genetic code” of violence and intolerance deeply embedded in the revolutionary gene. The revolution’s supporters, on the other hand, defended terror as the product of difficult circumstances, a regrettable but necessary expedient to combat the threats posed to the republic by civil war and military invasion.

**

Dichotomy.

The two sides of the debate are separated by their political associations with the events in question. Take away the sentiment-engagers — bread vs cake, revolution, Bastille, Marseillaise, the guillotine, the tricoteuses, the American revolution, Marx, whatever — thus viewing the image as simply one of contending forces, preferring neither one to the other, and the paradox resolves itself into a simple self-biting circle: the oppressed press back until they are themselves the pressors.

Jung knew this archetypal pattern — but I suspect he is little known in the history silo, and has indeed been expelled from the silo of the psychologists.

Somewhere in back of the event is a pattern, and when sufficiently abstracted the pattern will illustrate with commendable impartiality the forces in play in the whole.

For the analyst, that impartiality, that wholistic perspective, is pure gold.

For myself, it was Reason enthroned in Notre Dame that truly set my teeth on edge.

**

Image source:

Robespierre’s likely appearance, a forensic reconstruction

**

And a Happy New Year to us all!