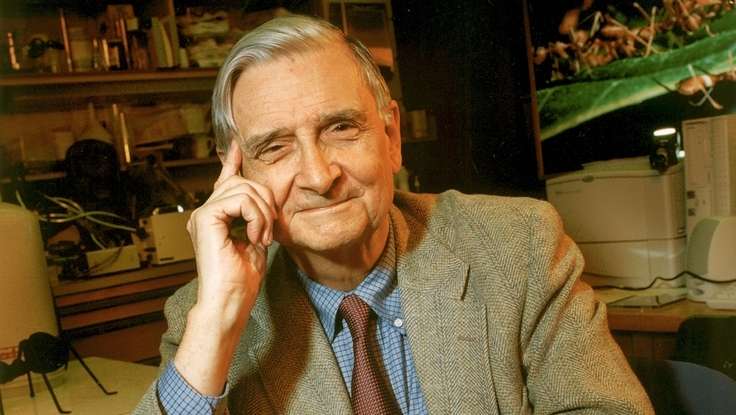

E.O. Wilson on the Evolutionary Origin of Creativity and Art

Last summer, eminent sociobiologist E.O. Wilson published an article in Harvard Magazine:

….By using this power in addition to examine human history, we can gain insights into the origin and nature of aesthetic judgment. For example, neurobiological monitoring, in particular measurements of the damping of alpha waves during perceptions of abstract designs, have shown that the brain is most aroused by patterns in which there is about a 20 percent redundancy of elements or, put roughly, the amount of complexity found in a simple maze, or two turns of a logarithmic spiral, or an asymmetric cross. It may be coincidence (although I think not) that about the same degree of complexity is shared by a great deal of the art in friezes, grillwork, colophons, logographs, and flag designs. It crops up again in the glyphs of the ancient Middle East and Mesoamerica, as well in the pictographs and letters of modern Asian languages. The same level of complexity characterizes part of what is considered attractive in primitive art and modern abstract art and design. The source of the principle may be that this amount of complexity is the most that the brain can process in a single glance, in the same way that seven is the highest number of objects that can be counted at a single glance. When a picture is more complex, the eye grasps its content by the eye’s saccade or consciously reflective travel from one sector to the next. A quality of great art is its ability to guide attention from one of its parts to another in a manner that pleases, informs, and provokes

This is fascinating. My first question would be how we could determine if the pattern of degree of complexity is the result of cognitive structural limits (a cap on our thinking) or if it represents a sufficient visual sensory catalyst in terms of numbers of elements to cause an excitory response (neurons firing, release of dopamine, acetylcholine etc. ) and a subsequent feedback loop. Great art, or just sometimes interesting designs exhibiting novelty can hold us with a mysterious, absorbing fascination

Later, Wilson writes:

….If ever there was a reason for bringing the humanities and science closer together, it is the need to understand the true nature of the human sensory world, as contrasted with that seen by the rest of life. But there is another, even more important reason to move toward consilience among the great branches of learning. Substantial evidence now exists that human social behavior arose genetically by multilevel evolution. If this interpretation is correct, and a growing number of evolutionary biologists and anthropologists believe it is, we can expect a continuing conflict between components of behavior favored by individual selection and those favored by group selection. Selection at the individual level tends to create competitiveness and selfish behavior among group members—in status, mating, and the securing of resources. In opposition, selection between groups tends to create selfless behavior, expressed in

greater generosity and altruism, which in turn promote stronger cohesion and strength of the group as a whole

Very interesting.

First, while I am in no way qualified to argue evolution with E.O. Wilson, I am dimly aware that some biological scientists might be apt to take issue with Wilson’s primacy of multilevel evolution. As a matter of common sense, it seems likely to me that biological systems might have a point where they experience emergent evolutionary effects – the system itself has to be able to adapt to the larger environmental context – how do we know what level of “multilevel” will be the significant driver of natural selection and under what conditions? Or does one level have a rough sort of “hegemony” over the evolutionary process with the rest as “tweaking” influences? Or is there more randomness here than process?

That part is way beyond my ken and readers are welcome to weigh in here.

The second part, given Wilson’s assumptions are more graspable. Creativity often is a matter of individual insights becoming elaborated and exploited, but also has strong collaborative and social aspects. That kind of cooperation may not even be purposeful or ends-driven by both parties, it may simply be behaviors that incidentally help create an environment or social space where creative innovation becomes more likely to flourish – such as the advent of writing and the spread of literacy giving birth to a literary cultural explosion of ideas and invention – and battles over credit and more tangible rewards.

Need to ponder this some more.

April 4th, 2013 at 1:46 pm

I thought a while back about writing a post on how music is an integral part of our brains. We’ve found bone flutes as old as some of the oldest flaked tools. We get earworms, even those who claim to be unmusical. And we all love rhythm and tones strung together in a sequence. It’s obvious that it’s a part of our brains.

.

But I didn’t write that post, because none of that constitutes proof in a scientific sense. I could have written an impressionistic piece, but that seemed unsatisfying for the time it would have required.

.

So Wilson knows a lot about ants, I’ll grant him that. He may even be the world’s greatest expert; I don’t have enough special knowledge in that field to make that judgment.

.

But I’ve been put off by his sociobiology from the first. It’s not much more than my post on music would have been – some intuitively attractive ideas, many correlations (or coincidences), and lots of opinion. Short on scientific evidence. And – whaddya know! – supportive of far too many ideas that males should be in charge. (Wilson draws himself up to full height, fingers his pipe: Sorry ladies, that’s just the way it is.)

.

I seem to be getting more demanding of scientific and logical proof as I get older, both of myself and others. This week alone I’ve irritated a couple of people by trying to pin down their definitions and train of logic. Maybe I’m just getting cranky in my old age.

.

Wilson would dearly love to be a Great Thinker. So “consilience” and now this piece. He tosses out some ideas that may be springboards for someone else who’s better at this. But these are such big problems that I wouldn’t be surprised if they are never solved. He does seem to be good at ants.

.

I read this piece, or as much of it as I could stand (somewhat over half) when you first posted it, Zen. Ugh, MOTS, was my evaluation.

.

I’m neutral on the individual-vs-group evolution thing. My sense is that probably both operate to some degree, but I would like to see some mathematical treatments. Anyone can make (and many have made) the qualitative arguments. Samuel Bowles of the Santa Fe Institute has done some of this, but more is needed, although I’m not sure that there ever will be a definitive proof. Wilson isn’t a mathematical guy.

.

Brain studies have to be taken with care. Alpha waves are sort of old-hat these days, but that doesn’t mean that studying them isn’t useful. But we still don’t really know what they mean. Likewise, brain scanning studies show parts of the brain lighting up with various behaviors or mental activity, but we don’t know what that means, either. Maybe we will someday. The brain project Obama announced this week wil help, but it’s likely to be a long time, even if Congress makes funds available and doesn’t pull the plug for political or allegedly fiscal reasons.

.

So Wilson takes something we don’t understand (alpha waves), correlates it with something else we don’t understand (abstract art), and concludes something or another. Besides sociobiology, the next most misused scientific concept of au courant thinkers is complexity. (Quantum theory probably fits in there somewhere.) Wilson doesn’t give a reference to the alpha wave studies, and he slaps complexity on stuff in a way that looks meaningless to me. Maybe it would make sense if he explained more, but I suspect not. Since Santa Fe is the home of SFI, we have more than our share of this kind of talking about complexity. I’ve asked people to explain when I run into this, and have never gotten an answer. Frequently they get mad at me.

.

So, what’s new? Cheryl is ranting against evolutionary psychology and BS uses of complexity. I get frustrated at these articles from Wilson that seem to have some great thoughts in them, but when I try to work with those great thoughts they just crumble.

.

I think that there are bits and pieces scattered throughout Wilson’s writings that can be a starting point for other thinkers, like you, Mark, to take off from. But the whole is less than the parts.

April 4th, 2013 at 3:02 pm

Cheryl,

.

Perhaps the role that Wilson plays, and others like him, is as much a part of the scientific pursuit as more empirical approaches. Mathematical, empirical, measurable pursuits have an enormous blind side: They may show us what is, in the form of abstract, detached data, but they alone don’t tell us a) where to look, and b) why to look, and c) what to do with what we see. Even the most strident purists in science seem to me to duck the issue of motive and motivation — in fact, they often seem to me to be using their “pure” observation as a cover for motives they themselves either don’t understand or don’t want to admit publicly, or as excuses for more abstract meta-scientific pursuits.

.

The subject of brain-mind mediation is a sterling example. I have often been half-amazed & half-pissed by the fact that the world is filled with scientists studying physical data who never once take seriously the fact that we, as a species and as individuals, still have absolutely no certain understanding of “mind,” however much we have learned about brains. The purists are content to use their minds without considering the fact that this first condition in their scientific pursuit, the mind, is entire enigma. (On the other side of the equation, philosophers…but there is enough to be said about that, positive and negative, to fill many blog posts.)

April 4th, 2013 at 3:23 pm

Curtis, I don’t see what Wilson is contributing in your schema. He would like to believe that he is contributing Great Ideas, like “consilience” (which hasn’t gone anywhere). But his logic there is faulty. And if he is going to make claims about group selection and individual selection, those must be backed up with something other than his great expertise on ants – otherwise known as mathematics.

.

It’s fine to start out conceptuallly – this is my mode of doing science – but you’ve then got to adduce evidence, which may be qualitative or mathematical.

.

I don’t see that Wilson’s Great Ideas are all that great or new. I would be more tolerant of his not backing them up if they were. As I say, there are some springboards in what he writes, but they will take better thinkers to do something with them.

.

I half agree with you on the subject of brain-mind. There have been a number of books lately on this very problem; it’s hardly ignored. I think that most scientists studying this have a great respect for the difficulty involved, although there are those on both the quantitative and philosophical sides of the issue who have lost sight of the other. And we have to start from where we are, whether we understand it or not. Definitions are important, and I suspect that you and I differ on those.

April 4th, 2013 at 3:56 pm

The “level of selection” debate is a big one in most biological circles. Wilson’s view is the minority; most do not even seen the individual, but the gene, as the unit in which selection occurs. (Dawkin’s <i>The Selfish Gene</i> is the most accessible and famous explanation of gene-selection.) But a group of determined scholars has been challenging this consensus in recent times. See this book, this book and this book. (I have not read them, just seen them referenced here and about).

.

Many anthropologists, of course, are fond of these ideas because then it means genes are not everything. On the flip side, I haven’t heard of a geneticist who was not a gene-selection guy.

April 4th, 2013 at 4:49 pm

Cheryl,

.

You seem to have a predisposition against the Great Idea of “Great Ideas”—I adduce this from your use of caps and repetition of the term in the preceding comment. I wonder if I should correlate the coincidence of “Great Thinker” in your first comment? Either way, our back-and-forth may or may not be useful, but I suspect that neither you nor I need fall back on a mathematical proof of the pixels we are seeing on-screen. In which case perhaps our conversation has little of the scientific pursuit in it?

.

That there have been and will surely continue to be examples of scientists (and philosophers, and others) exploring the subject of brain-mind does not seem proof enough that all scientists consider the problem as they are collecting data and presenting that data to their peers and the public. Although I haven’t surveyed all scientists now operating on the Earth and therefore can offer no charts as proof, I feel safe in saying that the vast majority do not give much weight to the brain-mind problem as they go about solving the Universe via observation and calculation. We might quibble on whether their studious ignorance of the problem matters much—I quibble with myself on that—but I don’t see how eliding that ignorance via recourse to “proof” that some have studied it does us much good. It is a question. If they aren’t going to ask it, maybe the fact that others are willing to ask it is a sign of some process of group selection in operation.

.

I am not sure what you mean by ‘like “consilience” (which hasn’t gone anywhere.)’ Since it is putatively a Great Idea, I wonder if you might offer examples of Great Ideas that have “gone somewhere,” for contrast. In some respects the question about Great Ideas, in context, seems to be a question about scientific methods. Some methods go somewhere, and some don’t; but respecting those that do, we might ask where they go and how they go there, and whether every destination imaginable can be accessed via a few universally viable methods.

April 4th, 2013 at 4:51 pm

“So Wilson takes something we don’t understand (alpha waves), correlates it with something else we don’t understand (abstract art), and concludes something or another.”

*

Wait, we don’t understand alpha waves, nor abstract art? Not even enough to know what dampening of an alpha wave could possibly mean, or how abstract art affects us, at least on a personal level?

*

It sounds to me like someone isn’t getting enough recognition from their potential that they were expecting out of life.

April 4th, 2013 at 5:29 pm

Larrydunbar – please cite the science behind what what Wilson is saying. He doesn’t. And please refrain from personal attacks.

.

Curtis, you and I have different approaches to many issues. That’s a good thing. But it can get us talking past each other, which I think we are heading toward. I frankly don’t see what your comments have to do with what Wilson is saying. That could be me or it could be you, or both.

.

I’d like to talk about Wilson. Why is what he’s saying interesting or scientifically grounded or new? My point is that I don’t see any of that. Do others?

April 5th, 2013 at 3:11 am

“But I’ve been put off by his sociobiology from the first. It’s not much more than my post on music would have been – some intuitively attractive ideas, many correlations (or coincidences), and lots of opinion. Short on scientific evidence. And – whaddya know! – supportive of far too many ideas that males should be in charge. (Wilson draws himself up to full height, fingers his pipe: Sorry ladies, that’s just the way it is.)”

.

Don’t know enough about the literature in field of sociobiology/evolutionary psychology on gender relations to comment responsibly beyond this: humans are also subjects of evolution and that prospect bothers many people for a disparate variety of reasons but ultimately because the biological implications of “X”, if proven scientifically, might be irrationally imported as justification in the political realm for policy “Y”. This is a reasonable political concern, given the history of the 20th century, but the science itself has to be looked at on scientific and not political grounds..

.

Secondly, culture appears to follow an evolutionary pattern and rigidly static cultures that are sustained for significant lengths of historical time(like ancient Egypt, the all time champion of cultural stasis, and to a much lesser extent, Sparta) are anomalies. Thirdly, disentangling cultural behaviors from genetic-driven ones is hard because many, perhaps most, human activities are a result of heritable factors, learned behavior and, at times, chance.

.

Cheryl’s criticism that Wilson’s musings here are speculative and not scientific are valid. Two points in Wilson’s defense: this article was not a scientific paper and no one with a halfway rational understanding of what science is would have thought it was (though I concede that leaves a large number of people who might. Presumably, those ppl don’t read Harvard Magazine on a regular basis). Secondly, speculation has it’s place as a precursor to conceiving a hypothesis or an experimental design. Even Newton and Einstein engaged in speculative projects which they had no hope of addressing experimentally but did as ideas for future investigations. Speculation is a positive good but eventually it needs to lead to experimentation and assessment of evidence.

.

I like consilience as a concept and to a lesser extent, an intellectual approach because it is useful to me. “Consilience” as a grand unification of all knowledge is not likely to come to pass any time soon; the weight of academic culture generally runs toward hyperspecialization though the trend in science to have cross-disciplinary and multidisciplinary teams in research as “normal” helps counter the former a bit.

April 5th, 2013 at 3:29 am

[…] on zenpundit.com Share this:EmailDiggStumbleUponFacebookPrintTwitterLike this:Like […]

April 5th, 2013 at 3:30 am

Hi Mark –

.

My objection to sociobiology is that it applies evolutionary principles to human behavior. Teeth, toe bones, jaws – all fair game for evolutionary studies. But behavior leaves no such hard remains. Sociobiology speculates how our ancestors lived and extrapolates to today. There is a lot of room in that for justifying one’s preferences, political and other. As you say, human activities result from a mixture of a number of factors.

.

I have no objection to speculation and agree with you that it has its place. I think, more than anything else, I continue to be disappointed by Wilson; he promises great things and seldom delivers. I agree that consilience is a useful concept, but it’s hardly Wilson’s alone.

April 5th, 2013 at 4:30 pm

The point about seven being the highest number of objects that can be counted at a single glance is further explored in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Magical_Number_Seven,_Plus_or_Minus_Two

The cited paper is useful for anyone who wants to develop criteria — don’t make them too complicated or numerous, because you lose the ability to differentiate between them.

April 5th, 2013 at 10:45 pm

The Magical Number Seven is a datapoint. However, it’s been taken too far:

Here is a comment from George Miller who wrote the original paper “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information”:

“

George Miller on the relevance of +/- seven

Here is a comment by the George Miller on the scope and relevance of his classic essay:

From: George Miller

To: Mark Halpern

Subject: Re: citation for your disclaimer

Many years ago landscape architects used my +/-7 paper as a basis to pass local laws restricting the number of items on a billboard. It was funded by the big motel chains; if you run a mom-and-pop motel you have to put a lot of information on your sign, but if you have a franchise everybody knows you have hot and cold running water, color televisions, free breakfasts, etc. The restriction on billboard content was driving the small motels out of business.

The same argument was used in the Lady Bird Johnson Act to prohibit billboards within X feet of highways, and the billboard industry (a strange group that deserves an essay of its own) was hurting. They hired a man to travel around from town to town trying to refute the claims that more than 7 items of information could cause accidents. The man’s wife did not like her husband being constantly on the road, so she asked him about it. He told her that the root of his trouble was some damn Harvard professor who wrote a paper about 7 bits of information. She, being herself a psychologist, said that she did not think that that was what Professor Miller’s paper said.

Armed with this insight, he looked me up and told me the whole story about my career, unknown to me, in the billboard industry. There was much more to it than I have outlined here, and I was shocked. So shocked that I wrote a long letter thing to set the record straight. The letter was published in the monthly journal of the billboard industry and that was the end of it. Unfortunately, I no longer have a copy of the letter an I don’t recall the name of the journal (this was all back in the early 70s) so I cannot quote to you its contents. But the point was that 7 was a limit for the discrimination of unidimensional stimuli (pitches, loudness, brightness, etc.) and also a limit for immediate recall, neither of which has anything to do with a person’s capacity to comprehend printed text.

If you want to quote the original article, it is on line and you can find a pointer to it at http://www.cogsci.princeton.edu/~wn. But if that is too time consuming – yes, you are right: nothing in my paper warrants asking Moses to discard any of the ten commandments.

Good luck, g.”

April 6th, 2013 at 3:53 am

““X”, if proven scientifically, might be irrationally imported as justification in the political realm for policy “Y””

Why irrationally?

Humans are organisms. Human conduct is determined by evolutionary factors because no organisms are exempt from evolutionary factors. We are here because we weren’t eaten. The conduct of every living thing is shaped by evolution.

And of course that has political implications.

I am surprised that this is even a question.

Evolution deniers are supposed to be Bible thumpers.

Evolution believers who otherwise like science don’t get to say, sure, knees and knuckles but not brains and sex relations and group behavior.

He who says A must say B.

April 6th, 2013 at 4:16 am

“Why irrationally? “

.

Fair question.

.

The irrationality aspect comes in many forms of logical fallacy or bad reasoning. One of the most common is an inability at the level of factual comprehension to understand comparative statistical risks. Another is an inability to discern between correlation and causation. We see this quite often with the EPA and FDA engaging in absurd levels of overregulation to avoid incredibly unlikely risks for very few ppl and the cost of foregoing wide-scale benefits for society as a whole. Many genetic factors or heritable traits that correlate with some behavior (positive or negative) are typically a part of the equation that goes into the behavior, not least including free will and personal responsibility for calculated actions. Many behaviors have not just one, but multiple heritable roots. In some cases, like with genetic diseases, the relationship is direct, clear and unimpeachable; but even here, good outcomes should not come at the expense of freedom of individuals who are not harming anyone else to make their own choices. A scientific case could be made that some individuals with genetic markers for certain kinds of cancer should not smoke, drink alcohol or eat high fat foods. To make that a political case based on that evidence that such conduct should be illegal is really nothing other than immoral tyranny.

.

Did evolution shape the brain and individual and group behavior (including gender) and even our social and sexual responses. Sure. I’d like to see what science has to say as to how and where. I’d be EXCEEDINGLY cautious before letting political ideologues use any of this as a basis to legislate . chances are, the first thing they would do is prohibit any research that might upset their ideology and thwart their ability to control others and dictate their lives by extrapolating out of context from research that did

April 6th, 2013 at 4:56 am

Politicians will seize on anything. That can’t be a reason to not talk about it.

My concern is more focused on not preempting discussion of evolutionary factors in human behavior. It seems almost as if Cheryl is saying there is an a priori prohibition on discussing these matters. But nothing is off or should be off the table for discussion. In particular, in this case it is not a matter of whether there are evolutionary factors in human behavior — there certainly are — but what they are and what impact they have.

This knowledge will be disruptive. So be it. Better disruptive knowledge than ignorance.

April 6th, 2013 at 9:00 am

I think it is irrational to believe that evolutionary factors, which describe past “success” (or survivability), should be useful for constructing policy which is meant to address present and future conditions. Evolution is intimately tied to environmental factors; environments change and have changed. There may be no good reason for assuming that evolutionary traits that were successful at one key point in the past will continue to be successful in the future. This is not to say that studying evolutionary factors is useless — in fact, such study might be quite helpful in isolating inherited traits that, though once quite useful, are now dangerous, given a changed environment. Another use of such study might be simply a better understanding of how environment and evolution work together…and modifying either biology or the environment, or both, in order to find a better future fit. (Here though you run into moral dilemmas like eugenics, the political and legal quandaries of posthumanism, etc. Nonetheless, we might already be doing it although largely unaware that we are.)

.

To get back to a point introduced in the post above, re:

.

“we can expect a continuing conflict between components of behavior favored by individual selection and those favored by group selection. Selection at the individual level tends to create competitiveness and selfish behavior among group members—in status, mating, and the securing of resources. In opposition, selection between groups tends to create selfless behavior, expressed in greater generosity and altruism, which in turn promote stronger cohesion and strength of the group as a whole.”

.

When I first read that, the phrase that bothered me most was “continuing conflict.” The phrase seems to me to be loaded with assumptions and perhaps to be a product of facile, pedestrian thinking. All of us feel the push-pull of individual desires vs. group demands; we are inundated with libertarian vs. socialist rhetoric; and so forth (and I am ever so tempted to introduce a bit of Nietzschean thinking here concerning the way “the herd” weakens individuals, demanding that they forsake selfish desires), but the dichotomy as presented, when it is used to define behaviors resulting from either type of selection, seems to play into those pedestrian notions too neatly.

.

I have for a little time now considered the individual/group question re: selection and evolution in this way: Other group members are environmental factors for the individual, in the same way that geology, climate, flora and fauna are environmental factors. Any selection process that favors “the selfish gene” or an individual’s genetic pool would include changes that helped the individual navigate that environment, survive that environment, exploit that environment — and alter that environment. This is where I place the birth of performativity: the survival within and exploitation and alteration of that portion of the environment comprising fellow humans.

.

Other humans are more variable, quickly-changing, than much of the non-human environment, even more changeable than non-human predators and prey, requiring survival strategies (within that environmental pressure) that could “keep up” with or address that variability. Intra-group competition would favor those better able to survive, exploit, and alter that human environment; but, other members of that environment would then become resources, in the way that water, flora, and fauna are resources: useful resources, that can be exploited, might be protected. (And maybe simpler to protect than other resources, given that these human resources also worked to protect themselves.) Usefulness might seem to be altruism, or weakness — people might seem to become sheep — but, as a selfish survival strategy, it might work. (Protecting human resources might seem like altruism; certainly, those current “job creators” we hear so much about think they are not exploiting, no, but helping the weak….while the putatively weak respond by saying “Protect us!” as a survival strategy — and so you have what we now call the United States of America.)

.

Early humans who were successful at exploiting of other humans did not breed with the non-exploited exclusively, far from it, so their genes would pass through the ranks of the exploited; eventually of course this meant that populations as a whole might improve over successive generations in areas related to this ability to survive, exploit, and alter their human environments. Important to note here that these interactions refer to performative strategies, worked upon other humans, and also that the effects of these performative strategies also altered the non-human environment. (A little OODA reference, here; or, WOODA, given the fact that Actions alter the World which is then Observed…) To what degree this alteration of the immediate physical environment by humans who were influenced by other humans…affected non-human evolutionary pressures…seems to be the open question. (I remember being taught in school, decades ago, that “Humans stopped evolving. Now it’s all about society, culture, etc.” — which seems a very old-fashioned myth nowadays.) But, if we break out of that old myth of Humans vs. The World, as if humans are not a part of the world — and so, accept that other humans are our environment, along with the rest of that world — we might be able to look at the way group dynamics, as a strong environmental factor, shaped evolutionary processes for early humans.

.

All the above might be boring theory, or even trite. My general complaint with the dichotomy presented in the snippet from Wilson might be summarized as: “the securing of resources” in his idea of selfish individual survival strategy seems to fail to recognize that other humans are resources; that human resources might be protected for selfish reasons; that human resources might work to benefit exploiters for selfish reasons; that cohesion might result from mutual exploitation; etc.

.

I suppose the missing link in the above might be a consideration of the way that group selection might work to promote individual genetic traits. I don’t find the idea odd that group selection might have actually promoted selfishness. (Would explain that in more detail if any of the above is unclear. But maybe as a quicky: the selfish sheep might want to stress how useful he can be.) But beyond that, and getting back to the idea of creativity, I don’t think the idea would be odd that exploiters who recruited, protected, and promoted human resources who were especially good at hunting, fishing, sewing, fighting, inventing, and so forth…would themselves benefit but also cause the spread of genes that aided in these traits.

.

If “altruism” indeed exists and has a genetic origin, I would guess it arose because of the general gap we have in observational capabilities — I mean, the variable, fast-changing humans in our environment cannot ever be known for certain in every respect, and our ability to process information is error-prone, so there might be a selfish reason for suspending judgment. Benefit of the doubt, so that not every affront causes an instant bloodbath among the group members. Maybe those who didn’t rush to judgment had a greater chance of survival; they could play the sheep but unleash the wolf (or shepherd) if necessary later.