The Islam we hope to read into Sisi’s al-Azhar speech

[ by Charles Cameron — bearing in mind Ian McEwan’s comment, “General Sisi or Isis — the palindrome is apt” ]

.

**

President Sisi of Egypt made a remarkable speech to the assmbled dignitaries of al-Azhar the other day. The Coptic Christian scholar Raymond Ibrahim has a translation of the relevant section:

I am referring here to the religious clerics. We have to think hard about what we are facing — and I have, in fact, addressed this topic a couple of times before. It’s inconceivable that the thinking that we hold most sacred should cause the entire umma [Islamic world] to be a source of anxiety, danger, killing and destruction for the rest of the world. Impossible!

That thinking — I am not saying “religion” but “thinking” — that corpus of texts and ideas that we have sacralized over the centuries, to the point that departing from them has become almost impossible, is antagonizing the entire world. It’s antagonizing the entire world!

Is it possible that 1.6 billion people [Muslims] should want to kill the rest of the world’s inhabitants — that is 7 billion—so that they themselves may live? Impossible!

I am saying these words here at Al Azhar, before this assembly of scholars and ulema — Allah Almighty be witness to your truth on Judgment Day concerning that which I’m talking about now.

All this that I am telling you, you cannot feel it if you remain trapped within this mindset. You need to step outside of yourselves to be able to observe it and reflect on it from a more enlightened perspective.

I say and repeat again that we are in need of a religious revolution. You, imams, are responsible before Allah. The entire world, I say it again, the entire world is waiting for your next move… because this umma is being torn, it is being destroyed, it is being lost — and it is being lost by our own hands.

**

Let me first draw a few relevant distinctions in regards to an Islamic Revolution (Sisi’s term), Reformation (cf Luther) or Enlightenment (cf Voltaire):

there is what Sisi would like to see there is what Sisi would like to communicate there is what various schools of Islam think Sisi intends there is what we would like to think Sisi wants to communicate there is what we would like to think Sisi would like to see there is what we ourselves would like to see

**

Mark Movsesian at First Things offers this caution:

Some are praising Sisi for his bravery. That’s certainly one way to look at it. When Sisi calls for rethinking “the corpus of texts and ideas that we have sacralized over the years,” he may be advocating something quite dramatic, indeed. For centuries, most Islamic law scholars—though not all—have held that “the gate of ijtihad,” or independent legal reasoning, has closed, that fiqh has reached perfection and cannot be developed further. If Sisi is calling for the gate to open, and if fiqh scholars at a place like Al Azhar heed the call, that would be a truly radical step, one that would send shock waves throughout the Islamic world.

We’ll have to wait and see. Early reports are sometimes misleading? there are subtexts, religious and political, that outsiders can miss. Which texts and ideas does Sisi mean, exactly?

That last comment in particular encapsulates my own response to Sisi’s speech. When Sisi speaks of “that corpus of texts and ideas that we have sacralized over the centuries” is he referring to the Qur’an? I am certain he is not. The ahadith of Bukhari? I strongly doubt it. The accumulated corpus of fiqh? That would be my guess.

Perhaps someone with access to the original of Sisi’s speech can clarify these matters.

**

In any case, it is worth noting that Sisi is not the first to make such a call.

Prof. Ali Khan‘s paper, The Reopening of the Islamic Code: The Second Era of Ijtihad, opens with the observation:

For more than a hundred years now, an accord has gradually emerged among Muslim scholars that Islamic classical jurisprudence (fiqh) must be reformulated to meet the needs of Muslim communities

In more detail:

Mainstream Muslim scholars and jurists from across the world seem to have reached a near-consensus that, although the Basic Code cannot be abandoned, it must be re-interpreted to establish legal systems that respect classical fiqh but also incorporate change. This evolutionary call — “that history, as a continuous movement in time, is a genuinely creative movement and not a movement whose path is already determined” — is made to extract Muslims from historical stalemate and expose them to ceaseless dynamism. Every day, in the words of the Quran, shines with new splendor, majesty and freshness.

What, in Khan’s view, comnstitutes the Basic Code?

This article is founded on a fundamental premise that the Quran and the Sunna constitute the immutable Basic Code, which should be kept separate from ever-evolving interpretive law (fiqh).

Khan notes:

Muslims have at least three options with respect to the Basic Code. First, they privatize faith, embrace secularism, and divorce lawmaking from the Basic Code. Second, they alter the text of the Basic Code to meet modern needs. Third, they accept the Basic Code as a permanent guide for individual and social life but see the Code as a flexible and evolutionary source.

He then comments:

The first option has been tried but the confrontation with religious forces opposing secularism has often maligned the secular state. The second option is unacceptable to all Islamic communities. The third option seems to be the most suitable alternative for the material and spiritual development of the Muslim world.

I hope that provides some background to Sisi’s remarks…

Another formulation of what we might look for from a renewal of Islamic scholarship comes from Bassam Tibi:

To me religious belief in Islam is, as Sufi Muslims put it, “love of God,” not a political ideology of hatred. .. In my heart, therefore, I am a Sufi, but in my mind I subscribe to ‘aql/”reason”, and in this I follow the Islamic rationalism of Ibn Rushd/Averroes. Moreover, I read Islamic scripture, as any other, in the light of history, a practice I learned from the work of the great Islamic philosopher of history Ibn Khaldun. The Islamic source most pertinent to the intellectual framework of this book is the ideal of al-madina al-fadila/”the perfect state”, as outlined in the great thought of the Islamic political philosopher al-Farabi.

And there’s plenty of reading to follow up on there…

** ** **

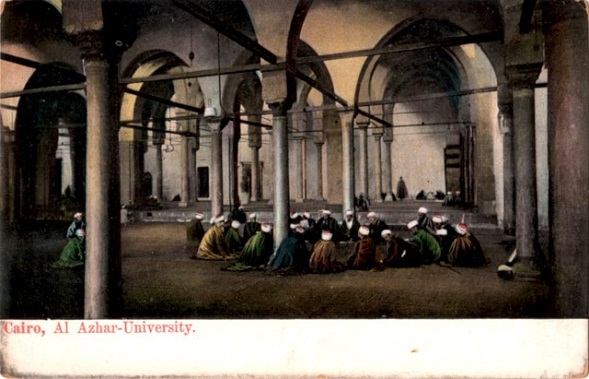

Older even than my beloved Oxford —

A lecture in al-Azhar mosque, Cairo, 12 December 2011. Photo credit: Tom Heneghan

— the tradition of Islamic scholarship at al-Azhar has been with us beyond than a thousand years.

January 14th, 2015 at 2:34 am

thanks for this. i have been wondering about al-Sisi’s speech. This helps. Can he/they pull it off do you think?

January 14th, 2015 at 5:33 pm

Hi Max:

.

The simple answer is, I don’t know. There are far too many factors playing into the situation, and I only track (or try my best to track) the specifically religious ones.

.

Your question did prompt me, however, to revisit some older readings of mine that may be relevant. I’ll make a new post.

January 14th, 2015 at 11:26 pm

I’m kind of amazed that we haven’t heard more about this.

.

There’s a lot of comparing Islam to pre-Reformation Christianity. But fundamentalism, literalism, only came to Christianity in the late 19th century. That would be more analogous to the Islamic fundamentalism that most of us would like to see reformed. So maybe there’s a commonality to the times that affects both religions (and Judaism, too, as a recent thing) similarly, rather than a need to reform Islam.

.

That said, any investigation into holy writings that will show them to be the product of humans (perhaps divinely inspired, if you think that way) and therefore interpretable is always to be encouraged.

January 15th, 2015 at 2:39 am

Hi Cheryl:

Indeed, that’s the thesis behind the University of Chicago’s brilliant & encyclopedic The Fundamentalism Project.

.

On a further note…

.

The topic of levels of meaning is one that fascinates me, but I’d need language and contextual skills in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Italian, Arabic and Sanskrit to begin to dig into it in any depth. In the meantime, a few quick notes:

.

Judaism:

.

A Chabad page describes the four levels of interpretation of a Jewish text as understood in Kabbalistic Judaism under the coverall term PaRDes:

Christian:

.

The classic statement of the Christian understanding of the levels of meaning is probably that of Dante in his Letter to Can Grande:

Islam:

.

This one I’ve lifted from Britannica:

Hindu:

.

As I understand it, Vedic thinking considers what we call sound under two heads, roughly corresponding to meaning and noise, and meaning (“shabd” which is often translated “sound” or “speech”) is then considered as having four levels:

A writer in the (somewhat literalist) Hare Krishna tradition explains:

I suspect there’s enough by way of hints there to give some polylingual scholar a very interesting thesis.

.

And one more thing.

.

While I’m about it, I think the same scholar should check to see the relationship between Logos and Dabar in Greek and Hebrew respectively, and Hindu Vac. My suspicion is that John 1.1 — “In the beginning was the Logos” — may not only speak to Greek and Jewish audiences alike, but also to any Brahmins on the shipping lanes in and out of Alexandria…

January 15th, 2015 at 5:00 am

So you are glossing “interpretable”…?

January 15th, 2015 at 3:44 pm

Very interesting Charles, I hope your scholar comes forward.

It could also be that John was speaking to the Brahmins that had allegedly been converted by Thomas the Apostle,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nedumpally

January 15th, 2015 at 4:44 pm

Hi Cheryl —

.

I’m really responding to your comment about literalism more than the one about interpretation, but i don’t suppose the two are very far apart…

January 15th, 2015 at 4:46 pm

Grurray:

.

If I might quote shamelessly from an unpublished and indeed incomplete work of mine from some while back:

As far as my friends have been able to determine on my behalf, the quotation Singh gives is in fact a conflation of two separate quotes from the Rig Veda — but still, if both parts existed in so central a Hindu text, they could well have been in the air of cosmopolitan Egypt around that time!