Al Farrow: an artist who leaves me uneasy, questioning

[ by Charles Cameron — art, religion, and violence ]

.

Al Farrow, the San Francisco-based artist, finds and shows us that violence which is one pole of religion — what I think of myself as the landmines in the garden, where the garden is pardis, pairidaeza, paradise, the opposite pole of religion — perhaps inseparable from the violence, perhaps separable — the pole of peace, eirene, salaam…

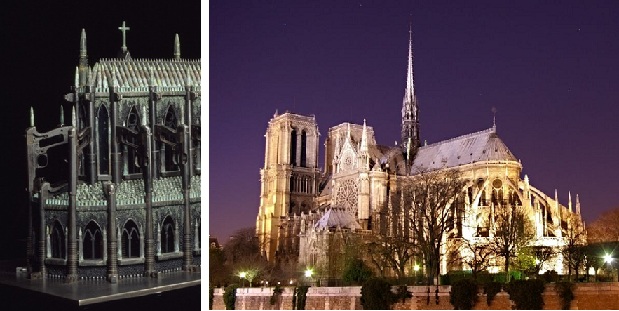

He show us this uncanny juxtaposition by building. meticulously, a cathedral out of guns and bullets:

His work leaves me impressed, but ill at ease, and for that I am grateful: he makes me think.

Take a close look at one of those flying buttresses… and compare it with its cousins at Notre Dame:

That detail really brings the power of Farrow’s work home to me.

*

William Blake suggested that it is the artist’s function to “cleanse the doors of perception” — to give us fresh eyes, to see the world anew for us.

Al Farrow does this: it is as though in his cathedral, Catholic and Protestant Ireland meet. Indeed, in an exhibit of his works — he has built mosques and synagogues of guns and bullets too — Christianity faces off against Islam, Judaism confronts its demons.

But there’s something more here, perhaps – the clash of war and peace, of hate and love — and how hatred can at times work with “love” as a protective shield…

Farrow himself says:

I am perpetually surprised by the historical and continuing partnership of war and religion. The atrocities committed in acts of war absolutely violate every tenet of religion, yet rarely do religious institutions speak against the violations committed in the name of God. Historically, Popes have even offered eternal salvation to those who fought on their behalf (The crusades, etc.).

In my constructed reliquaries, I am playfully employing symbols of war, religion and death in a facade of architectural beauty and harmony. I have allowed my interests in art history, archeology and anthropology to influence the work. The sculptures are an ironic play on the medieval cult of the relic, tomb art, and the seductive nature of objects commissioned and historically employed by those seeking position of power.

There’s considerable further irony, therefore, in the way in which Farrow’s already ironic work can be juxtaposed with it’s utterly non-ironic equivalent – Saddam Hussein‘s concept of the Mother of All Battles Mosque:

*

Farrow’s work does not instruct us to be warriors, nor to be pacifists – it draws our attention to the blend of violence and peace of which our human dreams and lives are made. As Farrow says in this video clip from an exhibit of his work in Washington:

I use real bones, real bullets, real guns, because fake bones wouldn’t shake anybody up, nor would a fake gun. The purpose of my work is actually to get people to think about that complex relationship between war and religion – or any violence and religion. And a lot of violence is committed and has been through history in the name of religion, and that’s an ongoing thing, in any part of the world you look.

And yes, I think it’s fair to say Farrow’s juxtapositions of religion and violence clearly lean us towards peace. War does the same, no?

War, after all, destroys places of worship, along with many and varied other places – munitions dumps and churches, mosques and homes:

But just as religion has its landmines, so too it offers us its gardens – and just as a mosque or church or temple may be a rallying point offering a divine sanction to violence, so too it may be a focus for peace and reconciliation.

Out of the ashes of destruction: creation, renewal, rebuilding…

For more on Al Farrow’s work, visit the Catharine Clark Gallery page. And feel uneasy by all means, meditate — the koan I am sitting with this month is “Stop the War” — and ponder…

September 7th, 2011 at 8:42 am

Charles — First, a belated thank-you for posting my essay on monarchism and thanks also to the ZenPundit readers who commented. Mark’s comments about the Oligarchy need to be brought out of the comment section and given their own post, which I plan to do at my blog. I am also planning a follow-up post to the monarchism one, which will incorporate the thoughts I expressed in my email to you, and which you encouraged me to post at ZenPundit. And I am still pondering your comments in response to my remarks about your "Alice’s Battlespace Wonderland" and when I can finish meeting myself coming and going I might have further comments.

.

Also, an aside to David Ronfeldt — many thanks for providing a list of your writings on swarming. Near the top of my to-do list is to write a follow-up post on the England riots and swarm/counter-swarm tactics but first I want to study your writings on the topic.

.

With regard to "stopping war" — what war are you talking about stopping, might I ask? Tommy Franks gave the U.S. two good invasion plans — one for Afghanistan and one for Iraq, which allowed the U.S. military to topple two governments and win two wars in incredibly quick time. Then the nightmare began, as civilians began micromanaging the mop-up period and occupation of both countries. To know in some detail of the horrors that the civilians overlords unleashed on their own countries’ troops and on Afghan and Iraqi civilians is to realize that there are worse hells than war.

September 7th, 2011 at 3:40 pm

Brilliant art. I like the way it represents the, ah, foundational role of violence in religion.

September 7th, 2011 at 5:50 pm

Hi Pundita:

.

I’m very much looking forward to your monarchism post, and will email you with a couple of quick comments later today. And it would be excellent to read your comments on the Alice’s Battlespace piece, too.

.

You ask "what war are you talking about stopping, might I ask?" — and that’s pretty close to what the koan asks of me, too: the koan itself doesn’t specify a war, it’s just a three-word phrase for me to ponder: stop the war. Perhaps there’s a literal war to be stopped, perhaps not.

.

Koans generally seem to address the person pondering them, so the injunction may be to stop some kind of war that’s raging inside me — a war between my clarities and my delusions, perhaps, or between my inner warrior (modeled on my father, Orford Cameron, DSC, RN, gunnery officer of HMS Sheffield in the battle of the Barents Sea) and my inner peacemaker (modeled on my mentor, the truly remarkable Fr Trevor Huddleston CR). I don’t know.

.

What I do find is that "sitting with koans" gives me a kind of insight that doesn’t answer questions so much as raise them — and the warrior / peacemaker paradox is certainly one of those for me.

September 7th, 2011 at 9:11 pm

People are always violent. Religion as a category is not very useful to understanding why people are violent. St. Louis IX was a crusader, a man of war, and his contemporary St. Francis of Assissi was … St. Francis. Who was more religious? Answer: Neither and both. Violence is human. Religion is human. A cathedral made of bullets is clever, but its a lie.

September 7th, 2011 at 9:12 pm

[…] The Trigger Finger Of Santa Guerro, And Other Interesting Artwork Hat tip to Mark over at Zenpundit. I am always on the lookout for interesting war related artwork, and I think this stuff definitely […]

September 8th, 2011 at 3:10 am

"Who was more religious? Answer: Neither and both"

.

The Zen monasteries of pre-Tokugawa, feudal Japan were invariably formidible military powers, at once zealously pious and splendidly martial. Samurai and Ronin would retreat there for periods of time to regain self-discipline and hone their contempt for death.

.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C5%8Dhei#13th.E2.80.9314th_centuries_and_the_rise_of_Zen

.

September 8th, 2011 at 7:21 am

"The Zen monasteries of pre-Tokugawa, feudal Japan were invariably formidible military powers, at once zealously pious and splendidly martial. Samurai and Ronin would retreat there for periods of time to regain self-discipline and hone their contempt for death."

—————-

Now that is some interesting trivia. Very cool.

September 8th, 2011 at 7:41 am

Hi Matt:

.

.

This is the cover image from Brian Daizen Victoria‘s book Zen at War, dealing with zen monks in WWII. See also his follow up book, Zen War Stories.

.

Nelson Foster and Gary Snyder commented, in a lengthy post on Tricycle:

While praising Victoria’s book in its overall thrust, they also said they felt his criticism of DT Suzuki in particular was unwarranted — a minor point in terms of the issue of Zen and the martial spirit as it continued into the twentieth century in Japan, but significant in terms of the history of Zen Buddhism in the West.

September 8th, 2011 at 2:18 pm

Hi, Charles — Thanks for your note. Have you ever seen the film, "Searching for Bobby Fischer?"

http://www.netflix.com/Movie/Searching-for-Bobby-Fischer/60001464

.

It’s based on the true story of an American boy with a gift for chess and it depicts his discovery of chess and his training as a chess player up to the time of his first major championship game.

.

The film focuses on the boy’s relationship with two brilliant chess players who become his teachers. The two men are polar opposites in playing style; one is a self-taught ‘street-chess’ player with a purely intuitive approach to the game; the other, a veteran of high-stakes championship play, is a master strategist for whom chess is pure technique.

.

The boy struggles to resolve his approach to the game and his feelings about chess as his teachers pull him in opposite directions.

.

There is also a ‘third force’ but here I will end so as not to be a plot spoiler.

September 8th, 2011 at 2:56 pm

“…there’s something more here, perhaps – the clash of war and peace, of hate and love — and how hatred can at times work with “love” as a protective shield…”

.

Just to run with this thought another example, the gross-point embroideries of Major Alexis Casdagli made while a prisoner of war in Germany. Casdagli passed the long hours in captivity by painstakingly creating a sampler in cross-stitch. Around the central inscription and decorative swastikas he stitched a border of irregular dots and dashes and over the next four years of captivity the work was displayed at the four camps in Germany where he was held. His captors never once deciphered the messages in Morse: "God Save the King" and "Fuck Hitler". It can be viewed here – the border is legible in ‘Preview’ mode.

.

He ran a needlework school for 40 other officers and was to say that the Red Cross saved his life and his needlework preserved his sanity. For more about his period of captivity see this story.

September 8th, 2011 at 4:56 pm

Hi Lex:

.

You write:

I’d respond that people are not "always violent" – but they have a violent propensity which has an understandable biological basis, and can be used offensively or defensively, for the sheer joy, honor and plunder of it, or in moderation and out of necessity – and which to my mind has verbal as well as physical expressions. So I’d say my own position is that of a strongly peace-inclined and reluctant warrior, rather than the frankly militant pacifist I once was.

Agreed. Religion as a field of study is, however, extremely useful in understanding what sanctions may be in place in specific instances or streams of violence – divinely sanctioned wars may have different recruitment patterns and different levels of commitment than state-sanctioned wars to which the individual conscience may take exception, for instance – and apocalyptically empowered wars have a peculiar urgency to them, and also a peculiar sense of the inevitability of righteous victory.

.

But none of this suggests that religion is *why* people fight – though it may explain why some people fight on some occasions, why some people refrain, some go to excess, some exercise moderation, and so forth. The concept of fard ‘ayn, for instance, is a critical theological construct for the recruitment of jihadis.

I don’t read Farrow’s cathedral as a statement – except to the extent that his work expresses his regret that what might be humanity’s greatest resource for peace is so often at the disposal of sectarian hatreds. And history is not without examples of wars fought on both sides in the name of God, as Lincoln knew:

The overarching theme of Al Farrow’s work, though, is to question the relationship of violence and religion, not to make a statement – and only a statement can be true or false, surely.

.

In saying this, I don’t want to give the impression that Farrow has no leanings of his own – his work is clearly not an expression of the glories of crusade or jihad – just that he is asking his viewers to think.

September 8th, 2011 at 10:32 pm

Charles, I took the sculpture to be a fairly heavy-handed statement that religion, and in this case Catholicism specifically, is really based on and built up on violence — symbolized by bullets — and hence as a statement, currently trendy to believe, that religion in general — and PC being what it is, Christianity in particular — is the cause of violence and of much of the (otherwise innocent and pristine) world’s misery. I suppose a more subtle response is possible to the piece, such as the reading you give to it.

September 9th, 2011 at 8:36 pm

Hi Lex:

.

Understood. I suspect the work leaves me uneasy precisely because I think there’s truth both in the beauty and nobility of religion and in its inherent capacity to grant "divine" sanction to tragic violence — so for me, it articulates both sides of a paradox.

.

The only other point I’d make is that Farrow is not in my view targeting Catholicism specifically — he has created similar works featuring mosques and synagogues, and indeed one of his mosques, which I illustrated above, has itself been a victim of warfare… and in his tape he talks about finding violence associated with non-Abrahamic religions, too.

September 10th, 2011 at 2:24 am

"… violence associated with non-Abrahamic religions, too." There have certainly been some very warlike Buddhists, as Mark noted. In fact, I think it is probably a pretty accurate generalization to say that every religion has a pacifistic element, including pacifistic communities or saints or cults. But that no major religion is entirely pacifistic.

September 10th, 2011 at 4:13 am

Pretty much agreed — I believe Farrow specifically mentioned the Buddhists vs the Tamils in Sri Lanka, and Hindutva fundamentalists vs Muslims in India.

.

I think its probably tough to be completely pacifist while Muslim, since the Prophet himself engaged in battles, but there’s certainly a tradition of nonviolence in Islam, see for instance Eknath Easwaran, Nonviolent Soldier of Islam: Badshah Khan: A Man to Match His Mountains. And Krishna at least overtly refutes pacifism in the Bhagavad Gita, although Gandhi read the book as referring to an interior battle.

*

Since I just shelved it today, I should also mention James Aho‘s Religious Mythology and the Cult of War, which distinguishes between two types of holy war:

I really need to read the whole thing very carefully. It’s an eye-opener.

September 10th, 2011 at 5:01 pm

Would submit that to make war is to be human. We’ve been doing since time immemorial, and I suspect for as long as man persists—sometimes in the name of religion, sometimes not. I suspect that won’t change anytime soon.

September 11th, 2011 at 7:28 am

It’s been around a while, all right — do you know Barbara Ehrenreich‘s book, Blood Rites? She locates the origins of wars in the ways by which humans moved from being prey to other species into becoming apex predators.

.

From my POV, what’s interesting is the way various religions and religious conditions affect the propensity for warfare, encouraging it, requiring it, indeed giving it divine sanction, intensifying it (as in apocalyptic time), internalizing it, setting limits to it, or opposing it.