The Mob of Virtue

Small “r” republican virtue, to be precise.

A wise man once told me that a weakness of our Constitutional system was that the Framers implicitly presumed that people of a truly dangerous character, from bullies to bandits to political menaces to the community, would primarily be dealt with in age-old fashion by outraged neighbors whose rights had been trespassed and persons abused one time too many. They did not prepare for a time when communities would be prohibited from doing so by a government that also, as a whole, had slipped the leash. Indeed, having read Locke, Montesquieu, Cicero, Polybius, Aristotle and Plato, they expected that such a state of affairs was “corruption” of the sort that plagued the Old World and might happen here in time. A sign of cultural decadence and political decay. They gave Americans, in the words of Benjamin Franklin, “A republic, if you can keep it”. It remains so only with our vigilance.

It is happening now.

We have forgotten – or rather, deliberately been taught and encouraged to forget – the meaning of citizenship.

We have let things slip.

Joseph Fouche superbly captures this implicit element, the consequences of the loss of fear of informal but very real community sanction, in his most recent post:

People Like Us Give Mobs a Bad Name

….A classic American mob could exhibit any or all of these strategies. It could be a saint inciting a mob to attack others who deviated from a shared narrative. It could be a knave in saint’s clothing inciting an attack on personal rivals. It could be a moralist inciting a mob against the local knaves. The one constant is that an American mob was an expression of communal self-government by moralists seeking to punish what they saw as deviant, even if its manifestation was frequently unpleasant. It was a sign the local people were engaged.

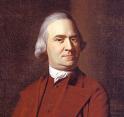

Samuel Adams was the Lenin of the American Revolution. He conceived a hatred for the British Empire and a desire for American independence well before anyone else did. Adams skillfully used mobs alongside legal pretense to incrementally spread his agenda. Others followed his example. In the Worcester Revolution of 1774, the local population shut down the normal operations of royal government in west and central Massachusetts and drove royal  officials out of those regions (the book to read is Ray Raphael’s The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord). The British crown lost control of inland Massachusetts before Lexington and Concord were even fought.

officials out of those regions (the book to read is Ray Raphael’s The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord). The British crown lost control of inland Massachusetts before Lexington and Concord were even fought.

Page 1 of 2 | Next page