[ by Charles Cameron — captivated by, capturing the light of the moon — a meditattion on art, science ]

.

**

According to The Smithsonian:

Great photography often comes down to snapping the right subject from the right vantage point at the right time. This image from NASA is just that. It was taken by the camera onboard the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite, one million miles away from Earth — the perfect spot to capture the Moon passing across the sunlit face of our planet.

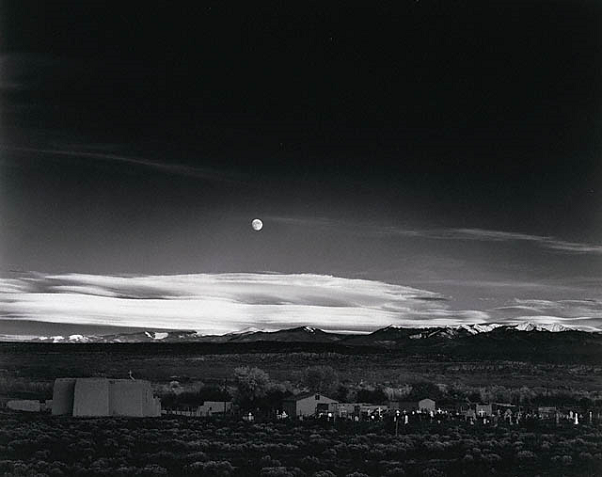

Nah, not really. As I said in an earlier post, Don’t you mess with my mother the moon, the great moon photo is Ansel Adams’ Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico<:

**

Yes, Adams’ photo captures “the right subject from the right vantage point at the right time” but it does so with a great eye — the eye, experience, vision of an Ansel Adams. The NASA photo of the moon transiting the earth, by contast, is brilliant, stunning, extraordinary — but offers sight, not insight. Once again, I think of Blake:

I question not my Corporeal or Vegetative eye any more than I would Question a window concerning a Sight. I look thro’ it & not with it.

That’s from his A Vision of the Last Judgment — apocalypticx, again — and famnously reads in context:

“What,” it will be Questioned, “When the Sun rises, do you not see a round Disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea?” O no no, I see an Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying “Holy Holy Holy is the Lord God Almighty.” I question not my Corporeal or Vegetative Eye any more than I would Question a Window concerning a Sight: I look thro it & not with it.

**

Ah, but how easy to quote the Ansel Adams imager — it has long been famous for being a great photograph.

And yet the greatness was in Adams, in the moment, not in popular opinion:

I had been photographing in the Chama Valley, north of Santa Fe. I made a few passable negatives that day and had several exasperating trials with subjects that would not bend to visualization. The most discouraging effort was a rather handsome cottonwood stump near the Chama River. I saw my desired image quite clearly, but due to unmanageable intrusions and mergers of forms in the subject my efforts finally foundered, and I decided it was time to return to Santa Fe. It is hard to accept defeat, especially when a possible fine image is concerned. But defeat comes occasionally to all photographers, as to all politicians, and there is no use moaning about it.

We were sailing southward along the highway not far from Espanola when I glanced to the left and saw an extraordinary situation – an inevitable photograph! I almost ditched the car and russed to set up my 8×10 camera. I was yelling to my companions to bring me things from the car as I struggled to change components on my Cooke Triple-Convertible lens. I had a clear visualization of the image I wanted, but when the Wratten No. 15 (G) filter and the film holder were in place, I could not find my Weston exposure meter! The situation was desperate: the low sun was trailing the edge of the clouds in the west, and shadow would soon dim the white crosses.

I was at a loss with the subject luminance values, and I confess I was thinking about bracketing several exposures, when I suddenly realized that I knew the luminance of the moon – 250 c/ft2. Using the Exposure Formula, I placed this luminance on Zone VII; 60 c/ft2 therefore fell on Zone V, and the exposure with the filter factor o 3x was about 1 second at f/32 with ASA 64 film. I had no idea what the value of the foreground was, but I hoped it barely fell within the exposure scale. Not wanting to take chances, I indicated a water-bath development for the negative.

Realizing as I released the shutter that I had an unusual photograph which deserved a duplicate negative, I swiftly reversed the film holder, but as I pulled the darkslide the sunlight passed from the white crosses; I was a few seconds too late

**

See: science.

Back in the day artists were alchemists — grinding their own colors from exotic shrubs (dragonsblood), insects (crimson lake), stones (lapis lazuli) and so forth — and remain so to this day, as in the case of Jan Valentin Saether:

Those shadows! The light..

**

Is Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, science, then — or art?

Is “art or science” even a real question?

And that “desired image” of a “cottonwood stump near the Chama River” — isn’t that in some way the negative of Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico? The drawn bow that propelled Adams’ arrow to its mark?