Archive for the ‘visualization’ Category

Simultaneity II: the pictorial eye

Wednesday, April 11th, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — when sequence becomes simultaneous, the pictorial eye, rethinking thinking, continuing from Simul I ]

.

What better day to begin writing this second post on simultaneity than the day on which Google celebrated the birthday of Eadweard Muybridge with a Google Doodle — not that I’ll get the post finished within those same 24 hours!

The film — sequence of frames? stills? which would you call it? — that Muybridge took of a horse, used in that Google Doodle [view it in motion, here], is celebrated as showing beyond a doubt that when galloping, all four of a horse’s hooves may be in the air at the same time.

But is it — Muybridge’s work product — sequential, ie a film, or simultaneous, ie the presentation of many moments at one time?

That question gets to the heart of an issue that all narrative faces, as we shall see. First, the pictorial side of things.

*

Hans Memling‘s Passion of Christ (above) tells the gospel narrative, from Christ’s entry into Jerusalem and the Last Supper through his crucifixion, entombment and resurrection to his appearances in Emmaus and by the sea of Galilee in one canvas, much as Bach’s Matthew Passion [link is to Harnoncourt video] tells major portions of the same narrative in three hours of unfolding musical drama.

*

David Hockney has recently been working on forms of what I can only call “asynchronous synchrony” — as exemplified here:

Stills from Woldgate 7 November 2010 11:30 AM (left) and Woldgate 26 November 2010 11 AM (right). Credit: ©David Hockney

This image comes from a fascinating article describing Hockney’s current work by Martin Gayford, titled The Mind’s Eye, which you can find in MIT’s Technology Review, Sept/Oct 2011:

We are watching 18 screens showing high-definition images captured by nine cameras. Each camera was set at a different angle, and many were set at different exposures. In some cases, the images were filmed a few seconds apart, so the viewer is looking, simultaneously, at two different points in time. The result is a moving collage, a sight that has never quite been seen before. But what the cameras are pointing at is so ordinary that most of us would drive past it with scarcely a glance.

As with the Muybridge video above, “the viewer is looking, simultaneously, at different points in time”. Here Hockney does this with video cameras — but he achieves something of the same effect of time-displacement with still photos, too, as you can see in his brilliant portrait of the sculptor Henry Moore, hosted on the British Council’s Venice Biennale site.

Here is Gayford’s concluding paragraph, tying Hockney’s work into the larger context of our need for multiple frames of reference:

“Don’t we need people who can see things from different points of view?” Hockney asks. “Lots of artists, and all kinds of artists. They look at life from another angle.” Certainly, that is precisely what David Hockney is doing, and has always done. And yes, we do need it.

*

Memling again — and here I have enlarged and “framed” four of the 23 scenes from the passion of Christ which he has incorporated in the one painting: the Last Supper, the Crowning with Thorns, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection — Thursday evening through Sunday, and from life to death and back again.

*

It was Holy Week for Christians just last week, so perhaps you will forgive my having been preoccupied with images of the passion during the season set aside for such meditations — but what I want to point out to you is timeless, and indeed brings the transcendent into the everyday. Let’s take a look at a Hitchcock film next, then, and see how a contemporary videographer Jeff Desom has remixed the already Hockney-like Rear Window [link to IMDb] to create his own time-lapse telling of the tale [link to Vimeo], from which I took this screen-grab:

*

Time-lapse — simultaneity? The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead once wrote:

The communion of saints is a great and inspiring assemblage, but it has only one possible hall of meeting, and that is the present; and the mere lapse of time through which any particular group of saints must travel to reach that meeting-place, makes very little difference.

And so it is with this other Memling painting — and many others like it, by artists old and new:

Here we see the Virgin Mary and Christ child with Saints Dominic and James — there’s an eleven centuries gap right there, St Dominic lived from 1170 – 1221, more than a millennium after Christ — and Memling has St Dominic presenting his patron, the spice trader Jacques Floreins with his family to Christ, circa 1490. With everyone dressed in late 15th-century fashions…

Whitehead — co-author with Bertie Russell of Principia Mathematica — see how amazing this is? — could have been thinking of Memling: “the mere lapse of time through which any particular group of saints must travel to reach that meeting-place, makes very little difference”.

*

Coming up next: how this affects our understanding of story.

____________________________________________________________________________

For an understanding of the setup David Hockney uses for his multiple-video takes, see here and specifically this and this. For the setup used by Jeff Desom in his Rear Window remix, see here and specifically this.

Simultaneity I: the palimpsest

Sunday, April 8th, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — simultaneity in art, life, theology, war and thought ]

.

We rip up the past to make room for the present, we staple the present onto the past, we lose much of the meaning our words and images once had in fragments, snatches and colors…

Even the staples eventually rust.

*

Still the past can at times be seen in the present, as earlier writing can still be seen in a palimpsest.

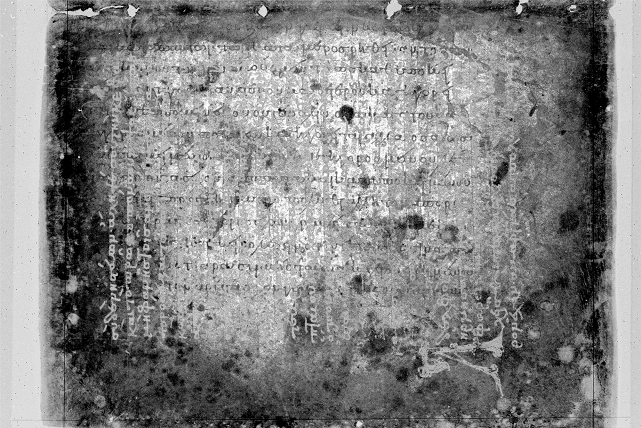

The Archimedes Palimpsest is [and I paraphrase] a Byzantine euchologion or prayer book manuscript, thought to have been completed by April 1229, and probably made in Jerusalem. Much of the parchment the scribes used in making the prayer book came from a earlier book of works by Archimedes, including his “On Floating Bodies” – a treatise of which no other copy survives. It seems the Archimedes manuscript dates back to tenth century Constantinople.

image credit: Archimedes Palimpsest Project

Erase Constantinople from your parchment, cut it and rotate it 90°, and you can build Jerusalem in its place. Peer deeply into prayer using multispectral imaging several hundred years later — and you may find combinatorial mathematics dating back more than two millennia…

What you are seeing in this image above is the workings of a mind two centuries BCE, transcribed in the tenth century CE, and made visible beneath and through other writing from the thirteenth, by twenty-first century tech.

So it is that Archimedes speaks to us today.

*

A palimpsest, then, is a layering of time on time, and the world we walk and talk in is itself a palimpsest.

The enduring, you might say, can be seen through the transient — the zebra crossing through the snow.

*

To see two times at once — to see history, accurately or otherwise, as a metaphor for today — is to see simultaneously.

As in Sergey Larenkov‘s celebrated photos, in which World War II and the present day coexist:

image credit: Larenkov, Wrecked tank “Tiger” in Tiergarten park

[ edited to add: Larenkov takes black and white photos from WW II, shoots the same scene in color from the same position today, and masterfully stitches them together digitally to create an image that allows the ghost of the past to seen in the present — brilliant! ]

Here again, as in the magically surreal sculptures of Nancy Fouts, we see the power of mapping one thing onto a kindred other of which Koestler wrote.

*

To tie all this back into the question of Which world is more vivid? This, or the next? — Stanley Hauerwas in his book, War and the American Difference: Theological Reflections on Violence and National Identity, suggests:

There is another world that is more real than a world determined by war: the world that has been redeemed by Christ.

He then clarifies his intent in saying:

The statement that there is a world without war in a war-determined world is an eschatological remark. Christians live in two ages in which, as Oliver O’Donovan puts it, “the passing age of the principalities and powers has overlapped with the coming age of God’s kingdom.” O’Donovan calls this the “doctrine of the Two” because it expresses the Christian conviction that Christ has triumphed over the rulers of this age by making the rule of God triumphantly present in the mission of the church. Accordingly the church is not at liberty to withdraw from the world but must undertake its mission in the confident hope of success.

*

Indeed, both Christianity and Zen would say that the greatest palimpsest is the palimpsest in which the transient circumstances of one’s life can all but obliterate the imperishable truth that underlies them — a palimpsest whose deepest layers may be read not with x-rays but by insight.

Christ lived in two times, or more accurately, time and eternity — to him the palimpsest was transparent, and thus he spoke (in John 8:58) what I suspect are the most profound five words in the Gospels:

Before Abraham was, I am.

Happy Easter!

Nancy Fouts and the heart of the matter

Thursday, March 22nd, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — Nancy Fouts, sculpture, juxtaposition, essence of creativity, pocket universes, Arthur Koestler, Mark Turner ]

.

Nancy Fouts is an American artist based in London. I ran across her work a while ago thanks to Michael Weaver on Google+, and was immediately struck by the intensity of her images, each one of which seemed like a landmark from a larger geography, more precisely focused and dense with meaning than our own world usually appears to be.

First impression:

.

The first image I saw was of a snail on the straight edge of a razor blade (above, left) — an image out of the script of Apocalypse Now to be sure, but presented by Fouts in sharp detail and unadorned by any other context, visually, direct from eye to mind and heart.

This may be the image many people first see of her work — very, very striking, exquisite, terrifying if you allow it to be so, and yet as clear and simple, almost, as a single drop of water on a leaf.

Singer and song:

.

But it was this next image that conquered me:

The juxtaposition is impeccable: sewing machine, record on turntable – and the overlap between the two, the link, the vesica piscis between them, is the needle.

The music of Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi — particularly on harpsichord — has been disparagingly called “sewing-machine music”. If that phrase gave rise to this marvelous image, perhaps the slight can be forgiven.

The sewing-machine? It’s a Singer. And in what must surely be an ironic, gender-influenced choice coming to us from an artist so assured and exacting — the music that the needle draws from the groove of the record is, as you can tell from the record label, the music of His Master’s Voice.

Philosophical aside:

.

I have pointed before to this diagram from Mark Turner‘s The artful mind: cognitive science and the riddle of human creativity, based on those in Arthur Koestler‘s The Act of Creation (eg those on pp 35 and 37):

It shows the essence of the creative act — the “release of cognitive tension” that occurs when some form of analogy, similitude, overlap allows the mind to join conceptual clusters from two fields in a “creative leap”.

Nancy Fouts’ work doesn’t merely make use of such twinned field overlaps, it makes twinned fields with overlap the defining quality of her works.

She is aiming right at the heart of the creative process. And it shows.

Moving further afield:

.

In that earlier post of mine, I talked about Ada, Countess of Lovelace, and noted that her analogy between Charles Babbage‘s Analytical Engine and Jacquard‘s mechanical loom, famously expressed by her thus:

The Analytical Engine … weaves algebraic patterns, just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and leaves.

was precisely the creative leap that led to the us of punched card systems in computation from Babbage to Watson…

I could give other examples. The Taniyama-Shimura conjecture which formed the basis of Andrew Wiles‘ proof of Fermat‘s Last Theorem, bridges two previously distinct branches of mathematics precisely by showing that for every elliptic curve, there is a related modular form…

And no, I don’t understand the mathematics. But I understand the concept of twinned fields, and the power of their overlap.

Some favorite tropes:

.

Back, then, to Nancy Fouts:

One thing that interests me about her work is that she has a few simple “essences” that she returns to time and again: in this case, bees, forms that resemble honeycombs, and by implication, honey.

In my own work, making similar connections between what we might paradoxically call “kindred ideas in unrelated fields” — I might set Nancy’s honeybees across from the verse from the Upanishads [Brihadaranyaka, fifth Brahmana, 14] which says:

This Self is the honey of all beings, and all beings are the honey of this Self.

Another of Nancy’s tropes connects nature and music…

The piercing:

.

And thimbles, those miniature emblems of armor and protection, are another recurring theme:

Let’s take a look at that last image, of the thimble transpierced by a needle.

I believe it has a history — again, accessible via an associative leap. Here are three images of the “wounded healer” motif, two of them specifically images of the Inuit shaman who has harpooned himself — a motif which the anthropologist and zen roshi Joan Halifax writes “captures the essence of the shaman’s submission to a higher order of knowing”:

Armor, the defenses we have in place to protect our selves, and vulnerability, the ability to to allow our selves to be wounded, so that the “self” which is “the honey of all beings” may shine through us. The paradox of Selflessness and Self.

Koan and sacrament:

.

Among wounded healers, we might count the crucified Christ, his side pierced by the spear of a Roman soldier — and here I might suggest that Fouts contrasts (image below, left) the self-sacrifice at the heart of Christianity with the pugilistic approaches of some proponents of his message:

And the image of Christ (right) balancing on a high wire?

Again I’m reminded of the language of shamanism. The anthropologist Barbara Myerhoff studied the religious beliefs and practices of the Huichol or Wixaritari of the Mexican Sierra Madre Occidental, with Ramon Medina Silva, a mara’akame or shaman of the tribe.

In her book, Peyote Hunt: The Sacred Journey of the Huichol Indians, she describes a feat of balance that Ramon performed, which appeared to serve a “sacramental” function for his people – providing them with what Cranmer‘s Book of Common Prayer calls “an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace”:

One afternoon Ramon led us to a steep barranca, cut by a rapid waterfall cascading perhaps a thousand feet over jagged, slippery rocks. At the edge of the fall Ramon removed his sandals and told us that this was a special place for shamans. We watched in astonishment as he proceeded to leap across the waterfall, from rock to rock, pausing frequently, his body bent forward, his arms spread out, his head thrown back, entirely birdlike, poised motionlessly on one foot. He disappeared, reemerged, leaped about, and finally achieved the other side. We outsiders were terrified and puzzled but none of the Huichols seemed at all worried. The wife of one of the older Huichol men indicated that her husband had started to become a mara’akame but had failed because he lacked balance.

It’s easy to read the description — but by no means as easy to keep one’s balance — something that Fouts’ image perhaps suggests more vividly than words easily can.

Richard de Mille describes the mara’akame‘s function in Huichol society as to “cross the great chasm separating the ordinary world from the otherworld beyond,” and suggests that Medina Silva’s feat of acrobatics on the barranca that day is to be understood as offering “a concrete demonstration in this world standing for spiritual balance in that world.”

Myerhoff herself was never entirely sure whether Medina Silva was “rehearsing his equilibrium,” or giving it “public ceremonial expression” that afternoon: it is clear, however, that for the Huichols, such feats of balance possess a resonance and meaning that extends beyond the “merely” physical.

Bringing the viewer into the picture

.

I may of course be projecting some of my own ideas onto Nancy Fouts’ work — and indeed, perhaps that’s the point.

She has some pretty fierce observations to make concerning matters religious — Christian, Buddhist and other — and I’ll leave those who are interested to make their own discoveries on her website. I don’t doubt there are places where her sympathies and my own overlap, and others where we differ.

Fouts speaks a direct and visceral language of images — and her juxtapositions, carefully chosen and choreographed as they are, provoke us to feel and think.

Thank you, Nancy.

No need to reach for the gun, fellas — but that’s art.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

credits for images of Harpooned Shaman: Charlie Ugyuk (left); David Ruben (right).

Countering Violent Extremism: variants on a theme

Saturday, March 17th, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — modeling / scoring CVE as a flow of ideas, with related matter from Hesse, Melville, Tufte, Rushdie and John Seely Brown ]

.

.

I am interested in thoughts: in the way thoughts connect to one another, differ from one another, lead to one another, parallel or echo one another, and oppose one another…

That’s my interest, that’s me.

1.

So when Will McCants of Jihadica posts the first two parts of his three-part series on Countering Violent Extremism (CVE), two points in particular strike me:

McCants proposes his own definition for CVE – “Reducing the number of terrorist group supporters through non-coercive means” – in part 1 of his presentation, indicating what in his view it should and shouldn’t involve, and in supporting this definition, he notes (recommendation #3):

The focus is not on reducing support for ideas, which is difficult to judge, but rather support for specific organizations that embody those ideas and seek their realization, which is easier to document and more closely related to criminal behavior.

In part 2, he mentions “thought police” twice, the second time saying:

But if counter terrorism is to involve more than just locking people up, it should not stray too far from stopping bomb throwers into social engineering and thought policing.

I’m definitely not into thought police either — but while I’d agree that ideas are by nature difficult to track or assess, that’s nonetheless where my own curiosity and creativity finds its level.

2.

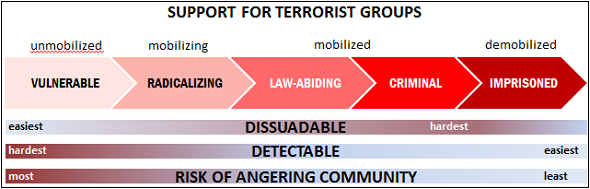

Just how CVE should operate in general is outside my scope — but since I do tend to focus in on ideas, I have the sense that paralleling McCant’s diagram of the approximate stages of support for terrorist groups:

or the version JM Berger reworked with McCants and posted on Intelwire, which I’ve placed at the top of this post — there could in theory be a diagram of the evolution of thought that accompanies those stages, and that such a diagram, intricate though it would undoubtedly be, might still be of some use.

3.

It seems to me that two main streams off thought – some might say “narrative” — would tend to flow together towards the eventual outcome of full radicalization and active jihad.

- One stream would begin with dissatisfaction and wend its way through a general sense of injustice in the world to the idea that Islamic nations and groups in particular are being targeted for military interventions by America and its allies, perhaps with a detour though the issues associated with “underdog” Palestinians, and thence towards a sympathy for jihadists, some level of identification with the Ummah, formal acceptance at some point of Islam (ie the taking of the Shahada), to an acceptance that jihad is an individual obligation for able Muslims under present circumstances…

- The other stream would arise from religious seeking and theological speculation, finding in Islam a simple and clear-cut answer to the seeker’s questions, via further discussion and the taking of Shahada — and then move along roughly the same trajectory that Daveed Gartenstein-Ross meticulously chronicled in his first, less widely known book, My Year Inside Radical Islam: A Memoir, with an emphasis on an increasingly “puritanical” salafi / wahhabi / deobandi interpretation of the religion, which can then lead in turn to a sense of potential political ramifications, again that the West is involved not merely in wars that happen to be in Muslim countries but in wars against the Ummah, and thence again to the acceptance of jihad as individual obligation.

That individual obligation (fard ‘ayn) being, I suspect, the likely “bottleneck” where any and all such streams would converge.

4.

For those interested in how this ties in with wider currents in contemporary thought, and with the bead game in particular:

I said above that I am interested in thoughts. I mean by this that my natural focus is more on thoughts than on people. Not that this is better or worse than some other focus…

In Hermann Hesse terms, I’m more interested in the great game of juxtaposed cultural contents played by the Castalians in his book Magister Ludi:

All the insights, noble thoughts, and works of art that the human race has produced in its creative eras, all that subsequent periods of scholarly study have reduced to concepts and converted into intellectual values the Glass Bead Game player plays like the organist on an organ. And this organ has attained an almost unimaginable perfection; its manuals and pedals range over the entire intellectual cosmos; its stops are almost beyond number.

than I am in the game that Hesse tells us he played in reverie while raking and burning leaves in his garden — visualizing the great men of all times walking and talking together across the centuries – a game which quite a few great minds seem to have stumbled upon, and which Hermann Melville describes in his novel, Mardi:

In me, many worthies recline, and converse. I list to St. Paul who argues the doubts of Montaigne; Julian the Apostate cross- questions Augustine: and Thomas-a-Kempis unrolls his old black letters for all to decipher. Zeno murmurs maxims beneath the hoarse shout of Democritus; and though Democritus laugh loud and long, and the sneer of Pyrrho be seen; yet, divine Plato, and Proclus, and Verulam are of my counsel; and Zoroaster whispered me before I was born… My memory is a life beyond birth; my memory, my library of the Vatican, its alcoves all endless perspectives, eve-tinted by cross-lights from Middle-Age oriels…

Both modes are valuable, I’d suggest, both are worth pursuing.

5.

Edward Tufte has the above diagram in Visual Explanations, one of his several beautiful and profound books. That diagram in turn is based on Salman Rushdie‘s description of the Indian epid Kathasaritsagara or Ocean of the Streams of Story in his book Haroun and the Sea of Stories:

…the Water Genie told Haroun about the Ocean of the Streams of Story, and even though he was full of a sense of hopelessness and failure the magic of the Ocean began to have an effect on Haroun. He looked into the water and saw that it was made up of a thousand thousand thousand and one different currents, each one a different color, weaving in and out of one another like a liquid tapestry of breathtaking complexity; and [the Water Genie] explained that these were the Streams of Story, that each colored strand represented and contained a single tale. Different parts of the Ocean contained different sorts of stories, and as all stories that had ever been told and many that were still in the process of being invented could be found here, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was in fact the biggest library in the universe. And because the stories were held here in fluid form, they retained the ability to change, to become new versions of themselves, to join up with other stories and so become yet other stories…

That diagram offers a quick approximation to the idea that I’d like to be able to model / diagram / score the ideas in play in CVE.

6.

If an idea is timely, it will find its kin — that’s one way to check that you’re not hopelessly out to lunch — and I certainly feel kinship with Tufte, Rushdie and Hesse here.

This, from John Seely Brown‘s opening keynote [video] at the 2012 Digital Media and Learning Conference, also strikes a kindred note for me:

How do you participate on the ever-moving flows of activities, knowledge and so on and so forth; how do you move from being like a steamship that sets course and keeps going for a long time to what you might call whitewater-kayaking, that you have to be in the flow, and you have to be able to pick things up on the moment, you gotta feel it with your body, you gotta be a part of that, you’ve gotta be in it, not just above it and learning about it. … In this new world of flows, participating in these knowledge flows is an active sport. And the whole catch is, how do you participate in these flows…?

7.

Ideas as flows, radicalization processes as flows — it’s mapping, modeling, and scoring them that really catches my own interest. It is still early days as yet…