The imagery of religion and war

Friday, September 9th, 2011[ by Charles Cameron — graphical analysis, selling bibles to teenage boys, tge Mass in time of war ]

.

Following on from my post on the work of Al Farrow, and leading towards a series of posts on ritual and ceremonial, I’d like to show you two very different images at the overlap of war and religion.

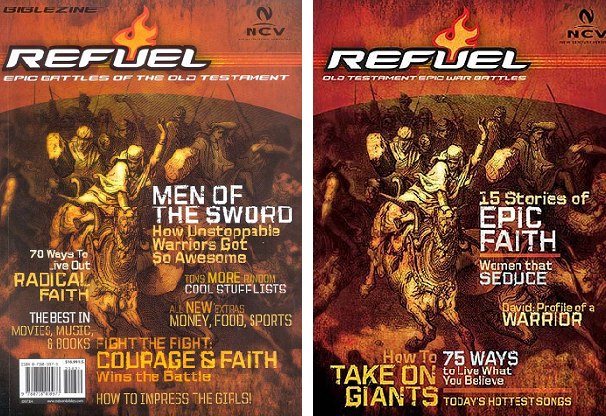

The first shows two different covers of the books of Joshua, Judges, Ruth, I & II Samuel, I & II Kings, Ezra and Nehemiah, as featured in a “biblezine” edition of the New Century Version of the Bible pitched at teenage testosterone.

Each of will have our own sense of whether that’s fun, stupid, Biblical, unBiblical, enticing, disgusting or simply uninteresting — but whatever your aesthetic and/or belief-based response, there’s a powerful lesson there in the choice of subtitles:

how unstoppable warriors got so awesome…

courage and faith wins the battle…

how to impress the girls!

how to take on giants!

women that seduce…

tons more random cool stuff lists…

I’m not a fan of this kind of thing myself, but I picked up a copy when I saw one at the thrift the other day — the one with Men of the Sword on the cover — and as someone who has done a fair amount of copy-editing in my day, was surprised to see “courage and faith wins the battle” (sic) had slipped past the editorial eyes at Nelson Books…

The New Testament in the same series is a bit better — the cover still features “dynamic stories of daring men” –but the, ahem, romantic element has been toned down a bit, with the catch phrase “class act: how to attract godly girls” replacing the Old Testament’s “how to impress the girls”.

* * *

Okay, I’m not as young as I once was, and maybe I’ve been mean enough at the expense of these people who want to market the Bible as though it was an invitation to warfare washed down with sex.

The other image I found recently comes a great deal closer to my own taste, and will serve as an excellent introduction to the idea of religious ceremonial as an oasis of peace in time of war:

Again, I suppose there may be some who will find the idea of religious ritual boring and irrelevant rather than beautiful — but it is its capacity to move us at a deep level — even (and perhaps particularly) when high tides of circumstance and emotion are breaking over us — that I wish to focus on and, to the extent that it is possible, explore and explain in some upcoming posts.

In my view, it was this kind of beauty, verging on the austere and the timeless, rather than the snazzy and faddish “impress the girls — draw in the kids” kind, that Pope Benedict XVI had in mind when he said:

Like the rest of Christian Revelation, the liturgy is inherently linked to beauty: it is veritatis splendor. The liturgy is a radiant expression of the paschal mystery, in which Christ draws us to himself and calls us to communion. As Saint Bonaventure would say, in Jesus we contemplate beauty and splendor at their source.

* * *

I am not a Catholic, though my sympathies run in that direction, and my examples of ceremonial will not be drawn only from Catholic or Christian sources — part of what i want to explore is the universal quality of ritual as a powerful source of motivation and inspiration, while another aspect has to do with the interweaving of military, religious and state symbols, but the point I would most like to make in each case is the profound impact that such symbols and rituals can have on the receptive heart.

I hope to touch on a wide range of ritual expressions, from the Requiem for a departed princely Habsburg to the Lakota sweat lodge, and from to the fire-walking ceremonial of the Mt Takei monks of Japan to the Spanish bull-fight, with a close look at the ritual surrounding coronation in my own British tradition.

For those who would like to peer deeper into these matters, I would suggest these four books:

Victor Turner, The Ritual Process

Geoffrey Wainwright, Eucharist and Eschatology

William Cavanaugh, Torture and Eucharist

Josepha Zulaika, Basque Violence: Metaphor and sacrament

The first explains “how ritual works” from an anthropological point of view, the second deals with the purposeful interweaving, accomplished within ritual, of time with the timeless, the third with the way in which sacramental transcendence is the very antithesis of torture, and the fourth with the impact of a sacramental sensibility within terrorism.

Each one is a masterpiece of intelligence and profound feeling.