Having previously tackled Bassford’s interpretation of the “fascinating” trinity and his argument for it’s dynamic nature, the time has come to observe how he explains a concept almost as important for understanding On War, what Clausewitz meant by “Politik“. We have all heard the often quoted maxim that Clausewitz said that “War was the continuation of politics by other means”, but what that sentence actually meant has been subject to both misunderstanding and debate. Here is Bassford:

….That leaves us with the problem of Politik. This is a huge subject, for it encompasses the entire issue of the relationship between it and war; perhaps 90% of debates about Clausewitz turn on it. Let us pause for a (long) moment and consider the meaning of those problematic words, Politik, politics, and policy.

Clausewitz seldom overtly defines Politik in any detail, and when he does so the definition is shaped to fit the immediate context. In translating Politik and related words, English-speakers feel compelled to choose between “politics” and “policy.” Some even prefer the much more specialized term “diplomacy,” which limits the discussion to relations among organized states—that is how Jomini’s Politique was usually rendered into English. Our choices can seriously distort Clausewitz’s argument. Clausewitz himself would probably have been very comfortable with the word “statecraft,” the broad zone of concerns and activities within which “statesmen” operate. But that term avails us no greater clarity and might even lock him exclusively into the state, where so many modern writers want to (uselessly) maroon him. We are interested in what Clausewitz meant by Politik, of course, but our focus here is even more on the question of what we mean by policy and politics. The latter two terms are related but far from equivalent. Each captures a part of the meaning of Politik, but even used together they do not cover quite the same ground.

…..1. Politics and policy are both concerned with power. Power comes in many forms. It may be material in nature: the economic power of money or other resources, for example, or possession of the physical means for coercion (weapons and troops or police). Power is just as often psychological in nature: legal, religious, or scientific authority; intellectual or social prestige; a charismatic personality’s ability to excite or persuade; a reputation, accurate or illusory, for diplomatic or military strength. Power provides the means to attack, but it also provides the means to resist attack. Power in itself is therefore neither good nor evil. By its nature, however, power must be distributed unevenly, to an extent that varies greatly from one society to another and within the same society over time.*25

2. “Politics” is the highly variable process by which power is distributed in any society:the family, the office, a religious order, a tribe, the state, an empire, a region, an alliance, the international community. The process of distributing power may be fairly orderly—through consensus, inheritance, election, some time-honored tradition. Or it may be chaotic—through intrigue, assassination, revolution, and warfare. Whatever process may be in place at any given time, politics is inherently dynamic and the process is always under pressures for change. Knowing that war is an expression of politics is of no use in grasping any particular situation unless we understand the political structures, processes, issues, and dynamics of that specific context…..

….The key characteristics of politics, however, are that it is multilateral and interactive—always involving give and take, interaction, competition, struggle. Political events and their outcomes are the product of conflicting, contradictory, sometimes cooperating or compromising, but often antagonistic forces, always modulated by chance…..

….War—like politics—is inherently multilateral, of course, though Clausewitz often uses the term sloppily in the sense of a unilateral resort to organized violence…..

….3. “Policy,” in contrast to politics, is unilateral and rational. Please do not confuse rationality with wisdom, however. As you may already suspect, there is no shortage of unwise policy out there. Policy (like strategy) represents a conscious effort by one entity in the political arena to bend its own power to the accomplishment of some purpose—some positive objective, perhaps, or merely the continuation of its own power or existence. Policy, is the rational and one-sided subcomponent of politics, the reasoned purposes and actions of each of the various individual actors in the political struggle.

….The key distinction between politics and policy lies in interactivity. That is, politics is a multilateral phenomenon, whereas policy is the unilateral subcomponent thereof.

….This makes policy and politics very different things—even though each side’s policy is produced via internal political processes (reflecting the nested, fractal *27 nature of human political organization).*28 This is not of merely semantic importance. The distinction is crucial, and there is a high price for confusion.

….In general, H/P’s word-choice reflects this logic, despite its strong bias towards “policy.” Whenever the context can be construed as unilateral, as in the Trinity discussion, we see “policy.” In Clausewitz’s final and most forcefully articulated version of the concept, however, the context is unarguably multilateral, with so strong an emphasis on intercourse and interactivity that, ultimately, even H/P is forced to use “politics” and “political”:

We maintain, on the contrary, that war is simply a continuation of political intercourse, with the addition of other means. We deliberately use the phrase “with the addition of other means” because we also want to make it clear that war in itself does not suspend political intercourse or change it into something entirely different. In essentials that intercourse continues, irrespective of the means it employs. The main lines along which military events progress, and to which they are restricted, are political lines that continue throughout the war into the subsequent peace. How could it be otherwise? Do political relations between peoples and between their governments stop when diplomatic notes are no longer exchanged?*30

….The clash of two or more rational, opposing, unilateral policies brings us into the realm of multilateral politics. Thus there really is no reason to avoid translating the Trinity’s politischen Werkzeuges literally, i.e., as “political instrument.”

That brings us to the problem of instrumentality. Force or violence is, of course, an instrument, in the sense of a hand-tool or weapon, of unilateral policy. War, however, must be bi- or multilateral in order to exist. Thus, while military force is indeed an instrument of unilateral policy, we should see war as an instrument of politics only in a very different, multilateral sense, as the market is an instrument of trade or the courtroom an instrument of litigation (“which,” as Clausewitz says, “so closely resembles war”)

….Clausewitz seems simply to assume that his readers will distinguish, on the fly, whether he is speaking in the unilateral or the multilateral sense. After all, he has stressed time and again the interactive nature of war, and, of course, his own language’s term Politik encompasses both our multilateral politics and our unilateral policy. But this casual stance results in constant confusion for the translator and the reader.

….We sometimes forget, of course, that Clausewitz’s magnum opus is not about policy or politics, nor about human nature or the nature of reality. It is merely a mark of the book’s profundity that these matters arise immediately in any serious discussion of it. In fact, Clausewitz himself dismisses the political complexities of policy in order to focus on his true subject, the conduct of military operations in war

….On the other hand, he’s offering some good advice here, not necessarily a prediction. It seems rather superfluous to suggest that perhaps Clausewitz actually grasped the facts that there is such a thing as bad policy, that bad policy has military consequences, and that this in turn may have consequences for both the political leadership and the community whose interests it is supposed to represent.

Clausewitz’s analogy to markets and litigation are interesting, partly because they are strained. Still useful, but strained.

In the case of the former, the relationship is actually the reverse: trading is an instrumentality of economic relationships and economic laws which continue to operate even if their “natural” manifestations are suppressed by political power wielded by the state (i.e. the Soviet Union or North Korea could fix prices or set quotas but then had shortages, surplus goods and black markets instead). However, in CvC’s defense, he was still correct that there was a degree of parallel between economic competition and war and economics was then still in it’s infancy. Some of the classical economists had yet to become regarded as such by wrestling with their own conception of iterative, friction-generating, relationships. Furthermore, in Clausewitz’s day, the heavy hand of the state in economic life was traditional in continental Europe while “liberalism” (allowing freer markets) seemed like a radical innovation rather than an underlying mechanism behind an existing system of distortions.

The same might be said that litigation is the instrument of the courtroom or justice, but I am less sure here. Continental legal traditions and assumptions are sometimes very different from the Anglo-American legal systems based more upon common law and the evolution of judicial independence from the executive. And unfortunately, early 19th century Prussian royal courts are a subject beyond my competence. In any event, the adversarial and zero sum nature of litigation carries through in Clausewitz’s analogy.

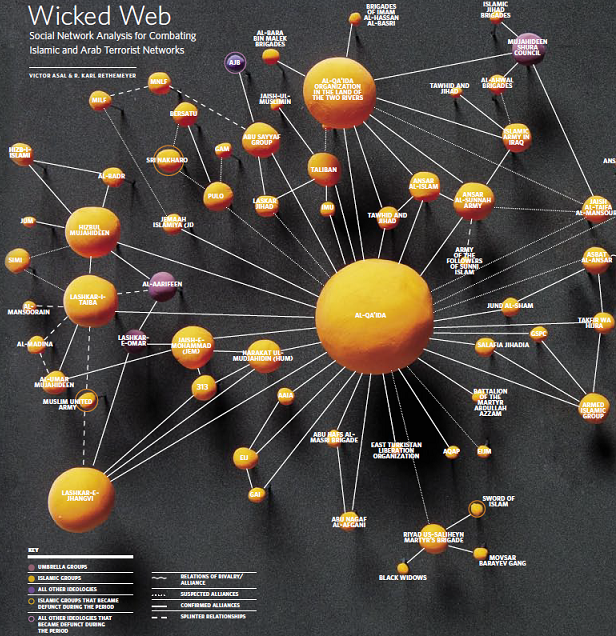

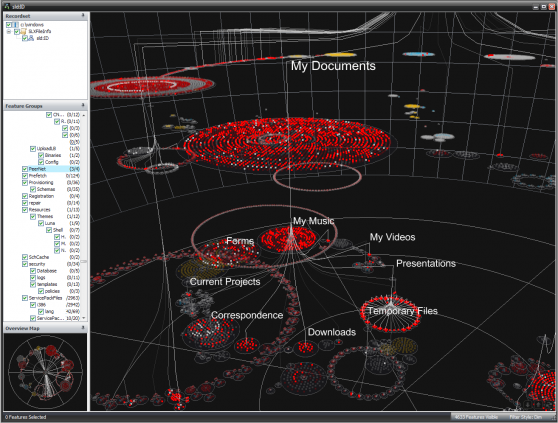

I am also intrigued by Bassford’s diagram. The representation of internal political dynamics is very useful but I am curious how he would weave a visual representation of strategy flowing from policy or (more accurately, policies) and strategy’s relationship with politics, beyond being subsumed. Many a potential strategy is stillborn in the tumult of bureaucratic-military politics, never mind the larger societal kind.