Striking Iran: game vs game

Saturday, November 19th, 2011[ by Charles Cameron — game and counter-game, FPS, Iranian nuclear attack ]

.

Following up on two earlier posts [i & ii] on gaming a strike on Iran — from the FPS leagues…

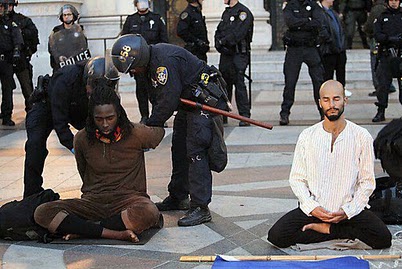

The upper image shows “the designer of the first Iranian made Nuclear Energy computer game”, according to the tag-line in the Sydney Morning Herald game review, Iranian game promotes sacrifice and martyrdom — the image credit is AP.

According to the review:

In “Rescue the Nuke Scientist,” U.S. troops capture a husband-and-wife team of nuclear engineers during a pilgrimage to Karbala, a holy site for Shiite Muslims, in central Iraq.

Game players take on the role of Iranian security forces carrying out a mission code-named “The Special Operation,” which involves penetrating fortified locations to free the nuclear scientists, who are moved from Iraq to Israel.

To complete the game successfully, players have to enter Israel to rescue the nuclear scientists, kill U.S. and Israeli troops and seize their laptops containing secret information.

But there’s more: the game itself is a “tit for tat” move in an overarching game of games:

The “Rescue the Nuke Scientist” video game, designed by the Union of Students Islamic Association, was described by its creators as a response to a U.S.-based company’s “Assault on Iran” game, which depicts an American attack on an Iranian nuclear facility.

That would be the US designed Kuma\War game, Mission 58: Assault on Iran, described in the lower of my two frames.

As a Special Forces soldier in this playable mission, you will infiltrate Iran’s nuclear facility at Natanz, located 150 miles south of Iran’s capital of Teheran. But breaching the security cordon around the hardened target won’t be easy. Your team’s mission: Infiltrate the base, secure evidence of illegal uranium enrichment, rescue your man on the inside, and destroy the centrifuges that promise to take Iran into the nuclear age. Never before has so much hung in the balance… millions of lives, and the very future of democracy could be at stake.

Seems like it’s hanging in the balance still — the Kuma\War game was released in 2005, the Iranian response in 2007.

one went to Obama and said, “Mr. President, what should we do?” Instead, ultimately, Obama was presented with a series of courses of action developed and proposed by his staff and various other agencies and departments, and the president was asked to select from a relatively constrained set of choices.

one went to Obama and said, “Mr. President, what should we do?” Instead, ultimately, Obama was presented with a series of courses of action developed and proposed by his staff and various other agencies and departments, and the president was asked to select from a relatively constrained set of choices.