Iran: The Debate We Should Be Having

Friday, July 24th, 2015By T. Greer

|

| Major religions in the Middle East Image Source: Columbia University’s Gulf 2000 Project |

——–

I am not a specialist in arms control or nuclear technology. I must rely on the judgement of others with relevant expertise to assess the viability of the new agreement with Iran. This makes things difficult, for the opinions of experts I trust are divided. Lawrence Freedman, Cheryl Rofer, Aaron Stein, and the other folks at Arms Control Wonk all support the deal. Most do so with great enthusiasm. Thomas Moore and Matthew Kroenig, on the other hand, oppose it with uncharacteristic harshness. Over at the excellent blog Zionists and Ottomans, Michael Koplow sticks to the middle ground. He accepts that the provisions of the JCPOA will successfully deter Iran from developing nuclear weapons, but worries that this focus on Iran’s nuclear program misses the forest for the trees. As he writes:

It is difficult to see how this deal advances conventional peace and stability in the Middle East over the next decade even as it pushes a nuclear Iran farther away. Contra the president’s assumptions, Iran is almost certainly going to use the money in sanctions relief to continue fighting proxy wars in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen, and continuing its general covert war with the Sunni world, not to mention its sponsorship of terrorism against Israeli and Western targets. By all means celebrate a temporary victory on the nuclear front, but the idea that this will bring peace in our time or stability to the Middle East is ridiculous. The impetus for the deal from the administration’s perspective has clearly been a conviction that Iran is changing socially and politically and that the regime cannot go on forever, and that a nuclear deal will empower moderates, create pressure from below for change, etc. This view is hubristic; I know of nobody who can accurately predict with any type of certainty or accuracy whether and when regimes will collapse, or how social trends will impact a deeply authoritarian state’s political trajectory (and yes, Iran is a deeply authoritarian state, liberalizing society and elected parliament or not). Certainly providing the regime with an influx of cash, cooperation on regional issues, and better access to arms is not going to hasten the end of the mullahs’ rule, so much as I find it hard to condemn the deal entirely because of some clear positives on the nuclear issue, I find it just as hard to celebrate this as some clear and celebratory foreign policy victory. [1]

Koplow is not the only person to express such concerns. In a thoughtful write up for the Brookings Institute, Tamara Coffman Wittes warns that this deal “will not stabilize a messy Middle East.” Kenneth Pollack’s recent testimony to the House of Representatives explores these themes in even greater detail, and should be required reading for anyone who wants to contribute to these discussions. (And of course, throw-away lines about Iranian plans to destabilize the region have found their way into almost every speech given by those who oppose the deal). [2]

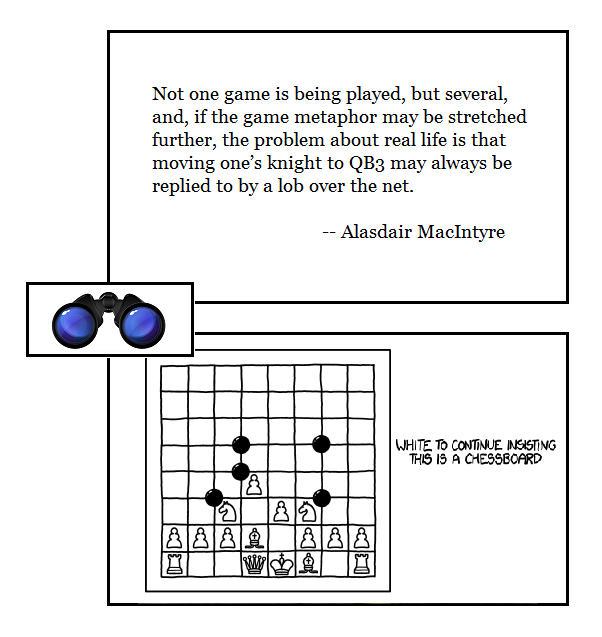

This is an important turn in the debate. For many the finer points of technical issue like uranium enrichment centrifuges or IAEA enforcement policies have been eclipsed by broad questions about Iran’s role in the regional order. These questions will only became more prevalent as the newness of this deal wears away with time.

This is not a conversation Americans are prepared to have. The mental model most American observers–and if their statements are to be taken at face value, American officials–use to make sense of Iran, America’s allies in the region, and America’s role in upholding the regional order are faulty and simplistic. You can see this quite clearly in comments like these:

Iran’s nuclear program—for obvious reasons—has been the most important issue in that country’s relations with the West, but it is very far from the only issue. Iran remains one of the most prolific state-sponsors of terrorism in the world. It has and will certainly continue to seek hegemony in the Middle East, to deliberately destabilize its neighbors and other states in the region, and to promote ballistic missile proliferation and human-rights abuses throughout the Near and Middle East and beyond.

Only a comprehensive strategy, led by the United States and supported by our major allies, can neutralize Iran’s malign activities, and this will take time. In particular, that program must take into account the views and interests of U.S. allies in the region, including Israel and those Arab States that understand and fear Iran’s ambitions and capabilities.[3]

The role played both by Iran and “U.S. allies in the region” is far more complicated than this. Each plays a part in the instability now wrecking the Near East. Like America, Iran’s relationship with other actors in the region is convoluted and sometimes contradictory. By simplifying the region’s geopolitics into a narrow contest of good and evil we do ourselves a great disservice. A more accurate narrative would recognize that there are two separate conflicts threaten the stability of the Near East. These conflicts are related but distinct. The failure to distinguish between them is the root problem behind much of America’s flawed commentary and confused policy.

The first of the two contests is the strategic rivalry between Iran and her regional enemies, Israel and the Saudi led Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). As with the great geopolitical contests of the last century, this rivalry has a hard ideological edge that makes compromise difficult. However, the ambitions of its central players fall squarely within the realm of traditional power politics. The roles each claim are as old as Thucydides, with today’s Persians playing the part of rising challenger to the existing order, and their opponents acting as its main defenders. This is a war of the shadows, waged through sabotage, assassination, espionage, terrorism, and the occasional full blown insurgency. The instability caused by American intervention in Iraq and the Arab Spring has raised the stakes of this competition. Now Tehran and Riyadh both desperately scour the region, ever seeking some new opportunity to tilt the balance of power in their favor. It is the civilians of the smaller powers caught in the middle that suffer most. That is where the proxy campaigns are fought. For the most part it is also where they end. But just below the surface remains the constant fear that these endless maneuvers in the shadows might lead to open war in the light.

It is to prevent such a war that analysts like Mr. Pollack—whose testimony to congress I urged you to read above—favor a strong U.S. presence in the region. This has been the traditional role of the United States since the ‘80s, with America acting as a guarantor of sorts of the existing order. Under such conditions Iran and the United States are natural enemies. When upstart dictators like Saddam Hussein don’t call attention to themselves, “maintain the regional order” is short hand for holding back the tide of Persian hegemony. It is important to realize, however, that no matter how hostile Iran and its proxies may be towards America, their power to harm American citizens and servicemen will always be proportional to how invested America is in the region. This was Ronald Reagan’s central insight when he ordered the withdrawal of American troops from Lebanon in 1984. Americans are only a target in the shadow war if they decide to participate in it.

This does not hold true for the second conflict that roils the Near East. (more…)