A Baghdad DoubleTake and other matters

[ by Charles Cameron ]

Zen recently posted a video of a terrific hour-plus-long speech by Doug Hofstadter – one of the best videos I’ve ever taken the time to watch – in which Hofstadter, the guy who brought us Godel Escher Bach and much more, talked about analogy and suggested that it’s at the very core of human cognition.

I posted a poem and some comments in response — they got a bit mangled in terms of formatting, which may be fixed by the time you read this – and Zen then posed a question:

Charles – there’s a large portion of visual imagery in the passage you cite: do you think the incorporation of imagery (thus activating a powerful region of the brain) enhances or distorts the underlying conceptual connection in an analogical construction?

That’s what set me off this time…

*

I think of a poem as a braiding of three strands: a strand of sound or music, a strand of image, and a strand of meaning. For convenience, I’ll usually include a fourth – wit – but it’s actually more like a pearl that can be threaded on the strand of meaning.

From my POV, the poem is thus essentially a screenplay for the mind’s eye – and if a poem begins with strong music, at the very least I’d like it to end with strong music, if it starts with wit or wordplay, I’d like it to end with that too, and if it has imagery, I’d like the images to unspool in a way not unlike the images in a movie…

When I’m reading poems by others, and particularly if I’m teaching a poetry class, I’ll sometimes notice a sudden disjunction in one of the three strands. If it’s clearly for effect, all’s well and good – but if it’s unconscious, unintended, it will always reveal an aspect of the poem that hasn’t been worked through yet, and applying conscious attention to it will result in the emergence of new material from the unconscious store that enriches the final product. Sometimes, that kind of attention reaches something that was psychologically difficult, a disjunction in soul if you like – and the result of moving through it to the finished poem can be very much like a breakthrough insight in therapy.

But “poetry is not a hospital” – if Apollinaire didn’t say that, and I used to think he did, I shall.

*

From my POV, therefore, there are analogies of sound, analogies of meaning, and analogies of image. There’s an analogy of sound between tomb and womb – we call it rhyme. There’s certainly an analogy of meaning – whence we come at birth, whither we go at death. And if you like, there’s an analogy of image – when I think of the “twinning” of those two words, I see life itself as running across a brief stretch of grass between two caves…

When as here, the analogy runs across all three braids, you have a very powerful “conceit” or poetic device.

The graphic match, together with sonic rhyme, between the visuals of a hotel room fan and the rotors of a helicopter at the beginning of Apocalypse Now parallels the sense of explosive heat and frustrated inaction of Captain Willard trapped in Saigon with the sense of freedom and clarity he feels when sent on mission up-river – again, an analogy in three strands.

*

But analogy can also cut across the senses in a different way. Here’s Hermann Hesse‘s view of the Glass Bead Game:

Throughout its history the Game was closely allied with music, and usually proceeded according to musical or mathematical rules. One theme, two themes, or three themes were stated, elaborated, varied, and underwent a development quite similar to that of the theme in a Bach fugue or a concerto movement . A Game, for example, might start from a given astronomical configuration, or from the actual theme of a Bach fugue, or from a sentence out of Leibniz or the Upanishads, and from this theme, depending on the intentions and talents of the player, it could either further explore and elaborate the initial motif or else enrich its expressiveness by allusions to kindred concepts.

Beginners learned how to establish parallels, by means of the Game’s symbols, between a piece of classical music and the formula for some law of nature. Experts and Masters of the Game freely wove the initial theme into unlimited combination.

That’s analogy cutting across disciplines, and across sensory modalities too.

There was a period of about a dozen years when I almost completely stopped writing poetry, and concentrated on devising a variant on Hesse’s game that would be playable on a napkin in a café – conceiving of it as an art that would combine tight form (think: sonnet, sonata) with the entire spectrum or palette of human thought, visual, verbal, numerical, aural.

Hesse again:

The Glass Bead Game is thus a mode of playing with the total contents and values of our culture; it plays with them as, say, in the great age of the arts a painter might have played with the colors on his palette. All the insights, noble thoughts, and works of art that the human race has produced in its creative eras, all that subsequent periods of scholarly study have reduced to concepts and converted into intellectual values the Glass Bead Game player plays like the organist on an organ. And this organ has attained an almost unimaginable perfection; its manuals and pedals range over the entire intellectual cosmos; its stops are almost beyond number. Theoretically this instrument is capable of reproducing in the Game the entire intellectual content of the universe.

And that was written before the world wide web allowed us to mingle visual, verbal, numerical and aural elements so directly in a single presentation.

You can imagine how delighted I was, therefore, to stumble upon Sven Birkerts‘ writing:

There are tremendous opportunities, and we are probably on the brink of the birth of whole new genres of art which will work through electronic systems. These genres will likely be multi-media in ways we can’t imagine. Digitalization, the idea that the same string of digits can bring image, music, or text, is a huge revolution in and of itself. When artists begin to grasp the creative possibilities of works that are neither literary, visual, or musical, but exist using all three forms in a synthetic collage fashion, an enormous artistic boom will occur.

That’s what the HipBone Games were all about…

*

That’s what I was reaching for, back in the days before I even called my games the HipBone Games — when they were still TenStones Games played on a board whose geometry I borrowed from the Sephirotic Tree – when I played TS Eliot‘s poem, The dove descending, in juxtaposition to Vaughan Williams‘ piece for violin and orchestra, The lark ascending…

…matching music with poem, descent with ascent, dove with lark, and the natural world of the English countryside with the “wrought” world of Eliot’s London in the pentecostal Blitz.

I don’t think Stephen or I had web browsers at the time – we played that game using AOL’s early texting function, so the music was entirely in the mind…

And I still think of that game as one of the loveliest expressions of the “hipbone” art.

Hesse’s game really is, for me, the continuation of poetry by other means…

*

But then it turns out that analogy is an incredibly powerful aspect of human thought – and one that, IMO, we haven’t explored very deeply, perhaps precisely because it jumps silos and disciplinary boundaries, and creates fresh insight…

…which is pretty much as Doug Hofstadter was suggesting in that video Zen posted.

And so this fundamentally analogical frame of mind — which I had developed in a poetic and aesthetic context and applied to the symbolism so dear to the poets, cultural anthropologists, analytical psychologists, and comparative theologians and the like — turned out to be highly applicable and seen as highly creative when applied to real world issues, when I got a job for a couple of years at a small think-tank just outside DC.

Because if linear causality is the warp of the weave of the world, acausal patterning is its woof (or weft) – and frankly, our current techno-civilization is hopelessly warped in the direction of warp, and has very little understanding of woof, of weft, of pattern — of what can only be learned from analogy.

*

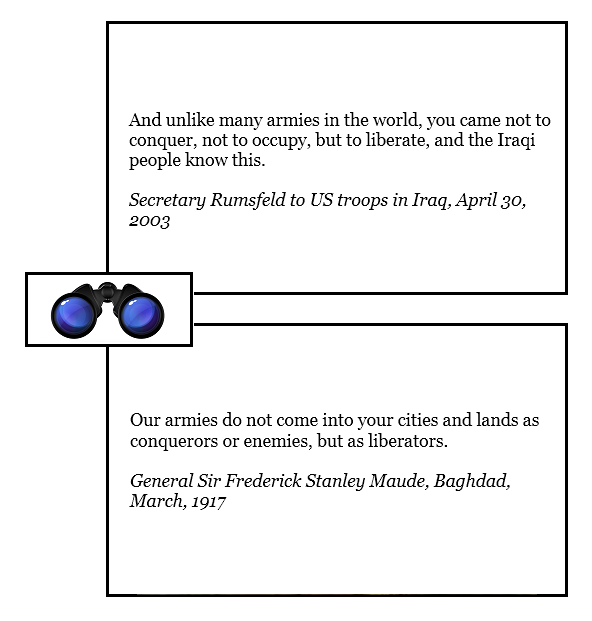

Not that there doesn’t have to be enormous care taken to avoid over-reading parallels. But consider the immediacy of the impact of this DoubleQuote, which I composed in 2003:

Eh, Zen?

Santayana echoes Marx refracts Hegel:

Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it

Seen from another angle: history has rhymes to match its reasons…