Formats for civil online debate II — inspired by Hesse’s Bead Game

[ by Charles Cameron — hypertext, rhetoric, glass bead games, civility ]

.

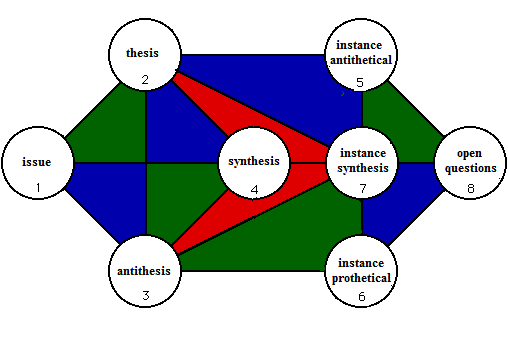

My second attempt at a format for online debate is, as I said, a variant on the “Dart Board” sometimes used for playing my HipBone Games (see, for instance, my solo game War is Sexy, says Dawn).

*

The idea here would be to format a blog post and series of 7 comments by a Querent (the one with the Question) who may also be the Umpire — both roles would be issue-neutral — a Proponent who would propose and support a thesis, and an Antagonist who would oppose it.And I should add, right at the outset, that this is a formal process for the named participants — as a white tie debate at the Oxford Union is a formal process — no matter how raucus the kibitzers may get, and accordingly requires a day or two between moves to allow for consideration, research and preparation.

The Querent makes the first move in the first position on the board, giving it short move title (short enough to be typed on the board graphic in the space currently occupied by the word “issue‘) and a paragraph or so of move content setting forth concisely the issue to be discussed — ideally via an issue neutral anecdote or quote. After each move, the Querent (or a graphically inclined observer) would ideally update and post the game board after inserting the relevant move title.

[ Those who are not among the named participants may of course kibitz at any time… ]

The Proponent next carefully chooses a pithy quote or anecdote, gives it a move title (as above), and posts the move title, the chosen move content (the anecdote or quote selected), the link claimed (setting forth concisely the nature of his or her argument as it relates to the move content of the Querent‘s issue), and if she or he so chooses, a comment (the comments in a HipBone Game are intended for meta-conversations among the various players).

The Antagonist then similarly chooses an anecdote or quote, and posts move title, move content, links claimed — in this case, showing the links with both the issue as stated at position 1 in the Querent’s move, and the thesis as stated in position 2 in the Proponent’s move — and a comment if so desired.

Okay, that’s thesis and antithesis, the Umpire then posts a move title, some move content and links claimed to all three positions in play, with a comment if so desired, in the fourth position (labeled synthesis).

The Antagonist plays next in position 5 — playing move title, move content, links claimed, comment — providing an instance with which to dispute the thesis, and linking as per the rule just stated to the thesis proposed at position 2 — only!

Since position 5 is only connected to position 2 of those positions in play, no other links should be claimed.

Similarly, the protagonist then plays in position 6, a move which I’ve called the “prothetical” instance without a clue as to whether prothetical is a real word — tho’ I like it — linking only to the antithesis in position 2, which it seeks to refute.

Move 7 is by far the trickiest of the game, and is made by the Umpire, who now has to provide move content that synthesizes the game thus far, explaining links claimed to positions 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 (ie to the original thesis, antithesis and synthesis, but moving the synthesis to encompass also the two instances)…

But the Umpire can take consolation in the fact that in the final move 8, the Querent gets to raise afresh those questions which remain — now that both sides have had their say, and the Umpire has attempted reconcile them.

*

Three quotes, the first one on debate:

Harmony among conflicting viewpoints, not the victory of one of them, should be the ultimate goal…

— from Bizell & Herzberg, The Rhetorical Tradition, as quoted here

The second moving from debate to dialog:

One way of helping to free these serious blocks in communication would be to carry out discussions in a spirit of free dialogue. Key features of such a dialogue is for each person to be able to hold several points of view, in a sort of active suspension, while treating the ideas of others with something of the care and attention that are given to his or her own. Each participant is not called on to accept or reject particular points of view; rather he or she should attempt to come to understanding of what they mean.

— David Bohm, Science Order and Creativity, p 86

And the third, from Buddhist Madhyamika philosophy, moving into the contemplative realm where all answers are seen as the stepping off points for open questions:

I wanted to use one word in Tibetan that I’ve found very useful for myself… and this is the word zöpa.. this translates usually as patience or endurance or tolerance, but there’s this very subtle translation of zöpa, which is the ability to tolerate emptiness basically, which is another ways of saying the ability to tolerate that things don’t exist in one way, that things are so full and infinite and leave you so speechless, and so undefinably grand – and these are just descriptive words, but you have to use some words to communicate, I guess — the ability bear that, that fullness, like we’ve been talking about, not turning away, not turning away.

— Elizabeth Mattis-Namgyel, in (if I recall) a Shambhala-sponsored retreat video

*

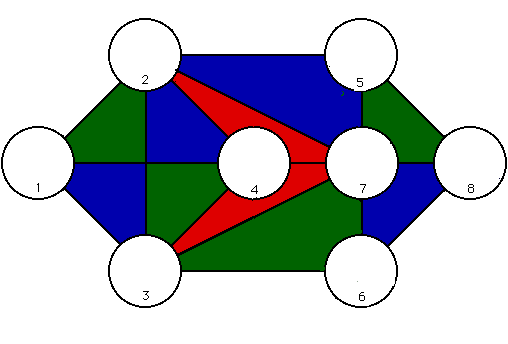

A blank Dart board, downloadable for your convenience:

August 16th, 2011 at 1:24 am

Charles,

What’s your opinion of IBIS (created by Horst Wessel, original conceptualizer of the "wicked problem") or argument mapping as potential constrained forms for more constructive online discussions?:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Issue-Based_Information_System

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argument_map

August 16th, 2011 at 4:47 am

Horst Wessel may have been a wicked problem for some, citoyen, but the originator of the "wicked problem" and IBIS notation was Horst Rittel <g>.

.

I think IBIS is brilliant — I know it via Jeff Conklin — and if I was running a conference with a brainstorming session, I’d certainly like to have a facilitation team-member whose task was to keep an IBIS mapping of the conversation. The best part, I think, is that it allows you to come back later to all the parts of a discussion that trailed off and got lost when something more interesting, or someone more interruptive, came along.

.

The most interesting other argumentation mapping I’ve seen is Robert Horn‘s work on mapping aspects of intellectual history at Stanford.

.

But both of these are free-form — they add nodes as required, like Tony Buzan’s mind-mapping and Gabrielle Rico’s clustering.

.

I’m after something else. I’m after analogies — not in these "debate" formats but in my games in general — because I think the quality of ideation that results from sustained emphasis on analogy rather than causality is extraordinary — and I’m after tight form, ie the use of pre-set (rather than free-form) graphs, for the same reason that poets often like to write under pre-set constraints (as exemplified by Robert Frost‘s remark that writing "free verse" was like playing tennis without a net): like the threat of execution, creative constraint tends to concentrate the creative mind.

.

You might be interested in a writeup of various sorts of graphical thinking I posted at Scribd.

August 16th, 2011 at 12:57 pm

The Glass Bead Game had a fundamental model in music. You have been presenting forms, in the sense of searching for structure; a frame at the developmental level of Bach.

.

But the clarity of the notes is what makes this difficult. For example, a recent conversation with someone about ‘financial institutions’ had to go through a clarification between the word ‘institution’ between a financial interpretation (‘corporation’) and a sociological one (‘set of norms’).

.

Musical notes, set in chords, and in point and counterpoint, don’t have the same ambiguity as words. Overtones of instruments (timbre) provide individual voices, but there is no ambiguity in the fundamental note, it is a mathematical specific, a frequency.

.

Focusing on the frame, I’ll say, leads to cacophany. For example, ‘there is one God’ creates a huge number of nodes without resolution. Observations without orientation.

.

Two orientations to consider. One is ecology; evolution, succession, that can be defined materially (number of organisms, biomass) and without so much ambiguity. Material resource flows. Perhaps updated to ‘follow the money’.

.

Another is mediation, rather than debate. Debates tend to be zero-sum in nature, a winner over a loser. This is also the courtroom frame. Mediation substitutes concerns for positions, and since the parties often have different concerns, both can give on areas of less concern and gain on areas of particular concern. This is akin to subsidiary themes resolving in a classical piece of music.

.

I’ll stop now. I want what you’re doing to succeed. It’s both beautiful and important.

August 16th, 2011 at 1:21 pm

In reviewing my post, I have two clarifications.

.

One is the difficulty of understanding without the structure being apparent. This to be resolved by the use of periods for paragraph spacing.

.

The other is that what I’m saying seems overly materialistic. I’ll let a quote speak for me:

.

Narrative rationality is the ability to think, make decisions, and act in ways that make sense with respect to the most compelling and elegant story you can improvise about a developing enactment. – Venkatesh Rao, TEMPO

August 16th, 2011 at 4:47 pm

Gesundheit!

Some recent pop science articles have postulated that human reasoning arose not from a need to find greater "truth" or "reality" but as a mechanism to discover and stockpile better mental constructs for winning arguments with other humans:

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/intersection/2011/04/25/is-reasoning-built-for-winning-arguments-rather-than-finding-truth/

For this tactical and forensic purpose, debate representations that implicitly draw on the idea of thesis/antithesis, perhaps to get to synthesis, are perfectly appropriate. But the search for truth, inasmuch as mere mortals can find the truth, may require a dialectical representation that randomly links a thesis with "now for something completely different", a "black swan", or a lolcat.

There’s a substrate within the works of Carl von Clausewitz and Col. John Boyd that hints that learning, often an overt plan for stockpiling ammunition for debates, and explicitly vomiting that learning out on unwary debate partners is not the road to greater awareness of the world around. What Boyd calls "orientation" and Clausewitz calls "coup d’oeil" seem to be sudden flashes of intuitive understanding that draw on multiple threads found amidst the cultural detritus the mind accumulated through out life.

The more explicit iteration of thought represented by some argumentation representations has its place. However Clausewitz and Boyd seemed to be aiming at education that would lay the seeds for producing individuals who could make implicit leaps towards truth rather than pound their opponents bloody in the trench warfare of ideational battle. That may be why they’re so hard to understand for some and their educational goals have been so hard to realize in others.

Human minds, when taken as an aggregate, have a strong tactical bias. People want a checklist. Producing a mind that has the right fuel and alignment to orient towards reality is a far harder educational task. Both Clausewitz’s and Boyd’s students were more dogmatic than their masters. For many of Clausewitz’s disciples it led to an obsession with decisive battle that contributed towards the bloody stalemate of WWI and for many of Boyd’s disciples it let to a fixation on wars of clever magic bullets that ignored the reality that strategy is a process of attrition.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder produces a somewhat analogous experience. The victim of a severe OCD attack faces the special horror of being mad (disconnected from reality) while being fully aware of their own madness (connected to reality). It’s like being trapped in the same head as stupid but you can’t escape. You’re condemned to watch your mental state deteriorate while you look on with full awareness. Other forms of mental illness can swallow you in an immersive blanket of delusion during an attack but the OCD sufferer lacks even that dubious mercy. My most severe OCD convinced me that, while there is a "reality" in the brain that is a pure construct of perception, there is also an outside reality that the brain is capturing and reflecting, however imperfectly.

Your mapping formats are optimized for a more positive manifestation of this effect, geared to produce serendipity through the chance meeting of disparate strands that give birth to that flash of understanding. Herr

Wessel’sRittel’s IBIS is an interesting tool for creating a more thorough shared understanding but I don’t know if it adequately includes that "now for something completely different" aspect of the search for a better gauge for the real. It and other "argumentive mapping" techniques have a place for producing sharper tactical performance but there’s a need for other formats that may lead to moments of "orientation"/"coup d’oeil" for those happy few who strive to get past the tactical mindset.I look forward to seeing more of your work here. It’s better than a bout of OCD.

August 16th, 2011 at 6:43 pm

Steve —

.

In light of your second comment, I edited your first comment to add paragraph breaks.

August 16th, 2011 at 7:53 pm

Steve:

Let me take this in parts.

Your point about the GBG and music is a keen one, and tempts me to the idea that a tone is not to its overtones as the denotative meaning of a word is to its connotative meanings. That’s not exactly what you’re saying, I know, but I like the tone : overtones :/: denotation : connotations formalism.

Notes in music, as you point out, have a specific frequency, and words are a lot less precise in that kind of way. That’s part of the reason I work in anecdotes and quotes, which I think of as analogous to melodic lines, or harmonic progressions like the folia or a twelve bar blues progression. In general, I’d say that quotes and anecdotes would carry a more precise sense than their constituent words taken individually.

You give the instance of "there is one God" as an example of possible confusion. A move in one of my games might juxtapose the Shema of Judaism (and specifically its claim about God) — "The Lord our God, the Lord is One" – with the Shahada of Islam (and specifically its equivalent claim) – "There is no God but God".

Contextually, each is the heart of the central profession of faith of the respective religions. Conceptually, each makes the claim of strict monotheism. But is the God of Abraham in Judaism the God of Abraham in Islam? That’s a question that hangs in the air, and perhaps we’d need to turn to Meister Eckhart’s distinction between God and Godhead, human concept and transhuman reality, to begin to explore it in detail.

My point is that juxtaposition is not assertion, it is inquiry, and my games are designed as much to elicit an understanding of differences as of parallelisms – indeed, the exploration of how a given analogy is inexact may prove to be the most revealing part of the exploration.

August 16th, 2011 at 8:14 pm

Steve:

Regarding your two orientations to consider. Jay Forrester‘s "stocks and flows" modeling does a great job of graphing the dynamics of quantifiable stock-and-flow systems, giving us access to the impact of feedback loops that the mind would not otherwise easily see.

My own wish is not to capture dynamics of what’s quantifiable, but the intellectual and emotional impact of what’s humanly expressible. So I’m interested in causality, but also, and more deeply, in associative play, memory, likeness, analogy and the like.

As regards your second orientation, "mediation, rather than debate" — I prefer collaboration to either one myself, and the principle use of my family of games has been as a collaborative art form, with solo meditation and group brainstorming in second and third place.

Mediation is certainly my preferred means of conflict resolution, but debate has its uses — and besides, it’s how a great deal of discourse has shaped itself. So from my POV, formats such as the two I’ve presented, that allow debate a somewhat even-handed means of presentation, have their uses…

And judging by your comment that "both can give on areas of less concern and gain on areas of particular concern" I’d say we have very similar approaches in that respect. Thank you for your kind words.

August 16th, 2011 at 8:29 pm

M. Fouche:

As usual, you have said more than I can adequately respond to, but your comment:

hits the nail on the head. The IBIS map catches what thoughts are articulated in a meeting, while my games are designed to elicit thoughts that might not otherwise occur to their players.

There are plenty of free form ways of mapping ideas, but it’s my sense that they need an additional stage — formal constraint.

Here’s why:

That’s Stanley Ulam, in Adventures of a Mathematician. And then, from a poet, we have this:

That one is T.S. Eliot, quoted in Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style and The Principles of Screenwriting, p. 133.

When I came up with the HipBone Games, what I wanted to do was to devise a tight form — analogous to sonnet or sonata — for the free play of associative and analogical thought, viable across the digital spectrum in accordance with a comment Sven Birkerts once made:

August 17th, 2011 at 12:33 pm

.)

August 17th, 2011 at 4:08 pm

Charles,

.

Thank you for these beautiful posts, they explain very clearly how the game works. Also, very interesting series of comments. I have these very disperse thoughts about your work and GBG that I wanted to share here, FWIW.

.

First: Quotations are a big part of the way you use the game. This brings to my mind Walter Benjamin and his carefully arranged massive collection of quotations. He was convinced that he had discovered/created a new way of expressing meaning. I believe that your GBG is the first practical realization of that way of linking (apparently) unrelated thoughts, images, quotations and other materials.

.

Second: Deleuze idea of a rhizome, as opposed to a tree, resembles a lot the way you connect thoughts in GBG.

.

Third: Deleuze’s concept of “territorialization” can be useful in understanding how constraints

imposed on the concatenation of thoughts can serve a purpose. If thought develops in an unpredictable pattern, pushed here and there by other thoughts, in an ever expanding and drifting way, structuring a conversation through GBG would be a way of “reterritorializing” it, enough to allow it to build into a coherent whole and not enough to crystallize and kill it.

.

Fourth: Being a student of Talmud, I can relate in a deep sense to what you wrote about the layout of its the pages. This, of course, was the result and not the cause of the way the rabbis discussed. But from today’s perspective, the distinction between these two views fades and we do in fact have a “rhizomatic” text, an "infinite sea" of thoughts and words.

.

Sorry if I am not very coherent. Maybe I need to play a game that would connect Talmud and Benjamin (via his all time friend Gershom Scholem) with Deleuze, hypertext (object of meditation of Deleuze’s friend Guattari) and the rhizome? Would have to include Borges, a very “judaic” writer (his own words) and the Aleph, that point of the universe where everything is connected and Leibniz, most admired by Deleuze and Borges and…well, you get the idea.

August 19th, 2011 at 6:26 pm

I just want to thank you for this, Guillermo –I haven’t found the time or clarity to respond to you as you deserve, but I want you to know that I am deeply appreciative.