Heart Line — a response to Bill Benzon

Wednesday, October 12th, 2016[ by Charles Cameron — design fascination — including a Mimbres rabbit with a supernova at its feet ]

.

Bill Benzon has been blogging a remarkable series of posts on Jamie Bérubé‘s drawings as recorded in the online illustrations to Michael Bérubé‘s book, Life As Jamie Knows It: An Exceptional Child Grows Up.

**

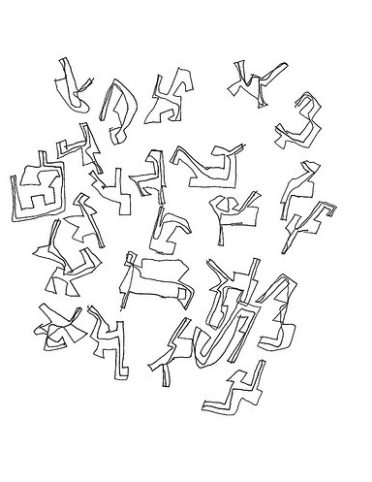

I wanted to respond to Bill’s latest, Jamie’s Investigations, Part 5: Biomorphs, Geometry and Topology, which included this illustration:

and these comments, which I’ve edited lightly for clarity and simplicity:

I emailed Mark Changizi, a theoretical neuroscientist who has done work on letterforms. He has been making a general argument that culture re-purposes, harnesses (his term), perceptual capacities our ancestors developed for living in the natural world. One of his arguments is that the forms used in writing systems, whether Latinate or Chinese (for example), are those that happened to be useful in perceiving creatures in the natural world, such as plant and animal forms. I told him that Jamie’s forms looked like “tree branches and such.” He replied that they looked like people. His wife, an artist, thought so as well, and also: “This is like early human art.”

You’ll see why that-all interests me — letters and life forms — below.

And then:

Yes, each is a convex polygon; each has several ‘limbs’. And each has a single interior line that goes from one side, through the interior space, to another side. The line never goes outside the polygon .. Why those lines? I don’t know what’s on Jamie’s mind as he draws those lines, but I’m guessing that he’s interested in the fact that, given the relative complexity of these figures and the variety among them, in every case he can draw such a line.

**

Two thoughts cross my mind.

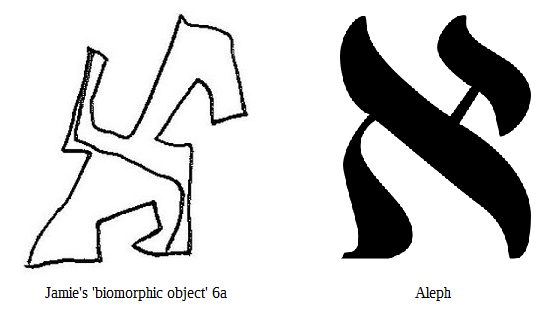

The first is that one of these forms, Benzon’s Biomorphic Objects 6a, bears a striking resemblance to the letter aleph, with which the Hebrew alphabet — or better, alephbeth — begins:

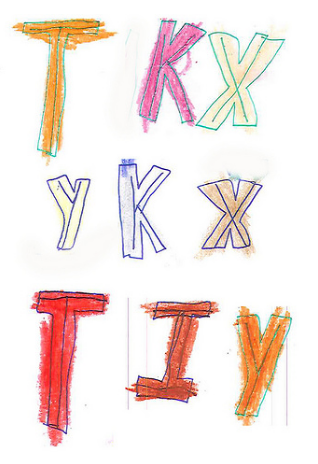

There may be some connection there, I’m not sure — though Jamie also has a keen interest in alphabetic forms, as illustrated here:

**

But it’s my second point that interests me more.

These “biomorphic objects” with “single interior line that goes from one side, through the interior space, to another side” remind me of nothing so much as the Native American style of representing animals with a “heart line” — best illustrated, perhaps, by this Acoma Pueblo Polychrome Olla with Heartline Deer:

The image comment notes:

One generally associates the use of heartline deer with pottery from Zuni Pueblo and that is most likely the origin. The fact that it appears on Acoma Pueblo pottery has been explained in a number of fashions by a number of contemporary Acoma potters. Deer designs have been documented on Acoma pottery as early as 1880, but those deer do not feature heartline elements. Some potters at Acoma have indicated that Lucy Lewis was the first Acoma potter to produce heartline deer on Acoma pottery. She did this around 1950 at the encouragement of Gallup, New Mexico Indian art dealer Katie Noe. Lewis did not use it until gaining permission from Zuni to do so. Other potters at Acoma have stated that the heartline deer is a traditional Acoma design; however, there is no documented example to prove this. Even if the heartline deer motif is not of Acoma origin, potters at Acoma have expressed that it does have meaning for them. It is said to represent life and it has a spiritual connection to deer and going hunting for deer.

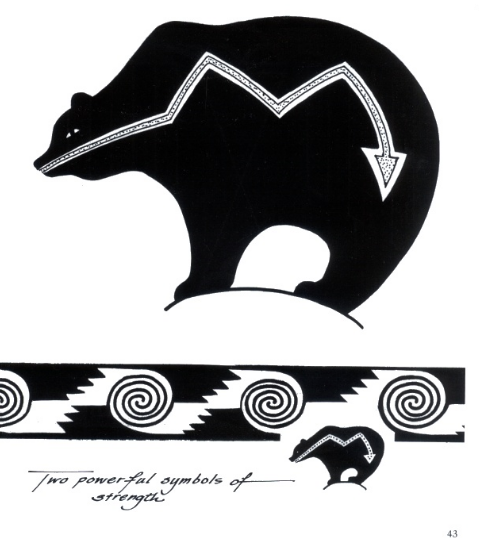

Here’s a “heartline bear” from David and Jean Villasenor‘s book, Indian Designs:

And here’s an equivalent Mimbres design for a rabbit with heartline, in which the line passes completely through the body from one side to the other, as in Jamie’s biomorphs:

Again, the comment is interesting — it cites a 1990 New York Times article, Star Explosion of 1054 Is Seen in Indian Bowl:

When the prehistoric Mimbres Indians of New Mexico looked at the moon, they saw in its surface shading not the “man in the moon” but a “rabbit in the moon.” For them, as for other early Meso-American people, the rabbit came to symbolize the moon in their religion and art.

On the morning of July 5, 1054, the Mimbres Indians arose to find a bright new object shining in the Eastern sky, close to the crescent moon. The object remained visible in daylight for many days. One observer recorded the strange apparition with a black and white painting of a rabbit curled into a crescent shape with a small sunburst at the tip of one foot.

And so the Indians of the Southwestern United States left what archeologists and astronomers call the most unambiguous evidence ever found that people in the Western Hemisphere observed with awe and some sophistication the exploding star, or supernova, that created the Crab nebula.

That would be the sunburst right at the rabbit’s feet!

**

Posts in Bill’s series thus far:

Jamie’s Investigations, Part 1: Emergence Jamie’s Investigations, Part 2: On Discovering Jamie’s Principle Jamie’s Investigations, Part 3: Towers of Color Jamie’s Investigations, Part 4: Concentrics, Letters, and the Problem of Composition Jamie’s Investigations, Part 5: Biomorphs, Geometry and Topology

My previous comment on #1 in the series:

On the felicities of graph-based game-board design: nine