Chet on TEMPO….Rao on OODA

Tuesday, July 26th, 2011

At Fabius Maximus, Dr. Chet Richards reviews TEMPO by Dr. Venkat Rao, enjoying the book as much as I did, if not more. Chet has some particularly incisive comments, positive and critical, in his review, which I suggest you read in full:

…Rao draws on Boyd in several places, as well on sources ranging from the topical, such as Gladwell and Taleb, to the foundational (e.g., Camus and Clausewitz), to the downright obscure – know anything about The Archeology of Garbage? Do the words wabi and sabi ring a bell?

The result is a synthesis, what Boyd called a “snowmobile,” that combines concepts from across a variety of disciplines to produce a cornucopia of new ideas, insights and speculations. You may be confused, challenged, outraged, and puzzled (some of the language can be academic), but you’ll rarely be bored because every chapter, often every page, has something you can add to the parts bin for building your own snowmobiles.

Let me highlight just a couple, of special interest to folks familiar with Boyd’s concepts. Near the end of the book, Rao introduces an expanded version of “legibility”:

A piece of physical reality is legible if it is obviously the product of coherent human agency, a deliberate externalization of a mental model. When human and natural sources of order are harder to tease apart, you get greater illegibility (p. 133 – and I warned you about the academic language).

Then a couple of paragraphs later, he claims that:

Used with adversarial intentions, Boyd’s OODA can be understood as a deliberate use of illegibility to cause failure.

At first, this seems silly. Boyd only considers conflict between groups of human beings (Patterns of Conflict, 10), so all uses of his strategic concepts would seem to be prima facia examples of legible phenomena. On the other hand, and this is an example of what makes Rao’s little book so valuable, some commentators, such as Stalk and Hout in 1990’s Competing Against Time, point out that victims of a Boyd-style attack can rarely identify the cause of their problems – often blaming bad luck or incompetent, self-serving and treacherous idiots in their own organizations. Boyd made this clear in his own work, such as in Patterns of Conflict, 132, when he suggested that his victims would exhibit a variety of traumatic symptoms including confusion, disorder, panic, chaos, paralysis and collapse – indicating unrelenting attack by forces outside the scope of their own mental models…

Chet concludes with a suggestion for Venkat (with which I concur):

…As for where to go from here, Rao might write more about tempo. This will seem strange to him, I’m sure, but pages go by with hardly a mention of the concept. This means that we need another book from him. I’d suggest expanding on some of the concepts that he raises but doesn’t find space to develop. Here are three ideas: […]

But you will have to go over to Fabius Maximus to read the rest. Venkat, in turn responded to Chet over at his blog, Ribbonfarm:

Chet Richards’ Review of Tempo on Fabius Maximus

….Overall, Chet comes to the conclusion that Tempo resonates with the Boydian spirit of decision-making. I don’t entirely get out of jail free though:

Perhaps his unfamiliarity with the original briefings, however, led him to make one characterization that is incorrect, although widely believed:

The central idea in OODA is a generalization of Butterfly-Bee: to simply operate at a higher tempo than your opponent. (118)

Guilty as charged. I didn’t spend enough time exploring how OODA gets beyond merely “faster tempo” to “inside the adversary’s tempo.” That’s something I hope to explore in a more nuanced way in a future edition. Over the last 6-8 months, I think I’ve come to understand the subtleties a lot better, and the challenge is to now spend more time thinking through clear definitions and examples….

I think everyone who has explored the OODA Loop concept, including John Boyd himself, initially gravitated to the aspect of cycling “faster” than one’s oponent because it is a natural assumption that resonates with our own experiences. We have all seen competitions where one player or athlete was “quicker” in reading situations and arriving at the right intuitive decision – usually most of us have been both the faster as well as the slower and more hesitant person. It’s the first scenario that springs to mind and being “faster” gives an obvious comparative advantages. Obvious does not mean “only” though.

What made the “faster” interpretation of OODA Loop really stick in the culture though, IMHO, was this unfortunate but easily understood graphic:

NOT THE REAL OODA LOOP

As a result, we get critical arguments that the OODA Loop is really something germane only to binary situations similar to the high pressure aerial combat that Boyd experienced in the Korean War or as a tactical fighter pilot instructor (or Musashi’s sword fighting) and not something generally useful in military strategy. An odd argument, given that Clausewitz liked to use binary metaphors to describe the nature of war.

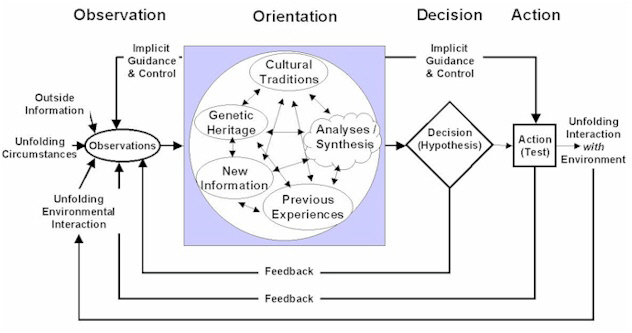

The next graphic, which better illustrates the simultanaeity and dynamic nature of the OODA Loop, with other potential avenues of exploitation than just going “faster” (which will swiftly hit diminishing returns in any event) does not lend itself as easily to nearly instant comprehension:

THE ‘OFFICIAL” OODA LOOP:

With these cognitive relationships operating continuously, mostly subconsciously with automaticity and in an iterative fashion, a different set of meanings to the phrase “inside your oponent’s OODA Loop” than just going “faster”, like a formula one race car zooming around a track.