[ by Charles Cameron — what hipbone thinking / gaming could and should bring to the natsec table ]

.

I have just been browsing the Institute for the Study of War‘s report on its ISIS wargame, and thought I’d wargame ISIS a bit myself, using my DoubleQuotes game.

**

The ISW report, in its 32 pages, barely mentions religious drivers, features one use of the word “apocalyptic” in a pretty non-specific sentence that implies nothing about what that word implies in terms of religious instensity — “ISIS intends to expand its Caliphate and eventually incite a global apocalyptic war” — and generally focuses on everything but “knowing” the enemy..

If they’d invited me and added a round or three of DoubleQuotes during a coffee break, I’d have been grateful for the coffee and the visit to DC, and very quickly played these two double-moves:

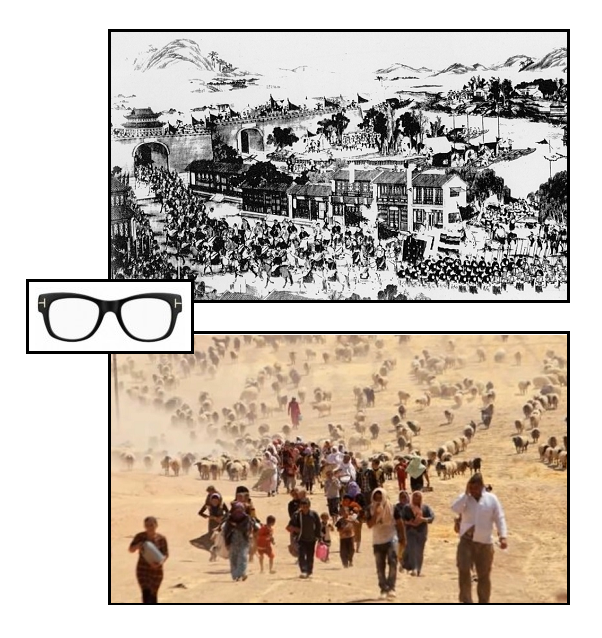

For wide context:

Upper panel: the Taiping Rebellion, an apocalyptic (in the true sense) movement in China, 1850 to 1864, with between 20 million and 30 million dead — as a reminder that apocalyptic movements can have, ahem, far-reaching consequences.

Lower panel: Refugees fleeing the Islamic State, a movement whose apocalyptic (in the true sense) strategy includes a focus on great end-times battle to be fought at Dabiq in Syria, Dabiq being the name of their English lnaguage magazine.

Read into the record in support of these two visuals:

Jonathan Spence, God’s Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan

William McCants, The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State

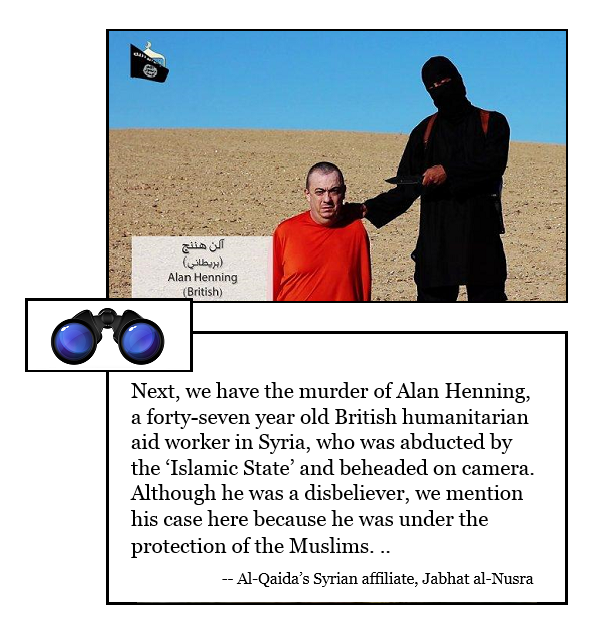

And with narrower focus:

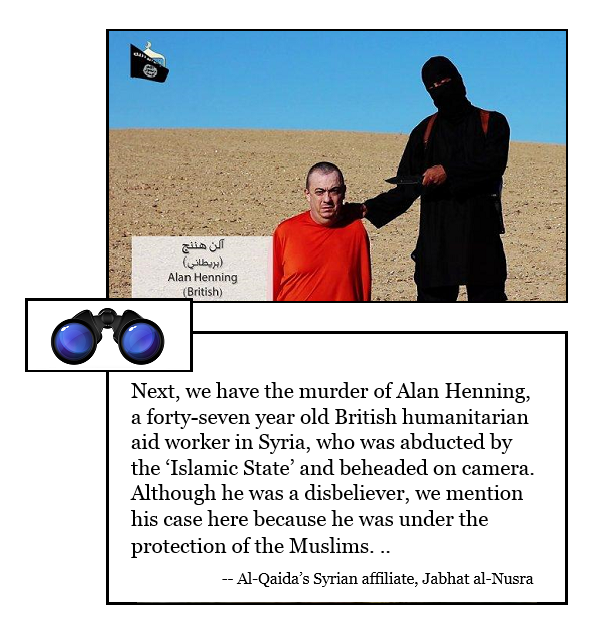

here, on the brutality levels permitted in two rival jihadist groups in Syria:

Upper panel: the Islamic State brutally executes British aid worker Alan Hemming

Lower panel: AQ affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra points out that he was under an offer of protection binding on all Muslims.

There would be background reading to explore and expand that DoubleQuote too. But the main point is: the contest of ideas, not simply that of troop movements and materiel, would have been part of the picture.

**

The Atlantic Council has also held two wargaming sessions on IS [1, 2], but again the insights to be gained into the Islamic State’s end-times motivations and their implications are almost nonexistent:

ISIS carries the seeds of its own destruction primarily because it has an extremely small constituency within Islamist populations around the world, an apocalyptic vision, an unsustainable strategy of us-against-theworld, and a failed governance project.

And that’s about it.

**

McCants’ presentation at the Boston conference, and his forthcoming book (above), both make it clear that the apocalyptic stress of today’s “caliphate” has morphed significantly from the more immediate apocaypticism in IS’ Zarqawi-era predecessor, Al Qaeda in Iraq.

And for a nuanced understanding of time-urgency in apocalyptic rhetoric, Stephen O’Leary‘s Arguing the Apocalypse: A Theory of Millennial Rhetoric is the definitive work.

So when do we start introducing ideational war (and/or peace) games alongside our games of brute force?

And how do you factor esprit, morale, and “angels, rank on rank” (Quran 8.9, 89.22) into troop movements and so forth?

Hint: they’re force-multipliers.