Simultaneity I: the palimpsest

Sunday, April 8th, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — simultaneity in art, life, theology, war and thought ]

.

We rip up the past to make room for the present, we staple the present onto the past, we lose much of the meaning our words and images once had in fragments, snatches and colors…

Even the staples eventually rust.

*

Still the past can at times be seen in the present, as earlier writing can still be seen in a palimpsest.

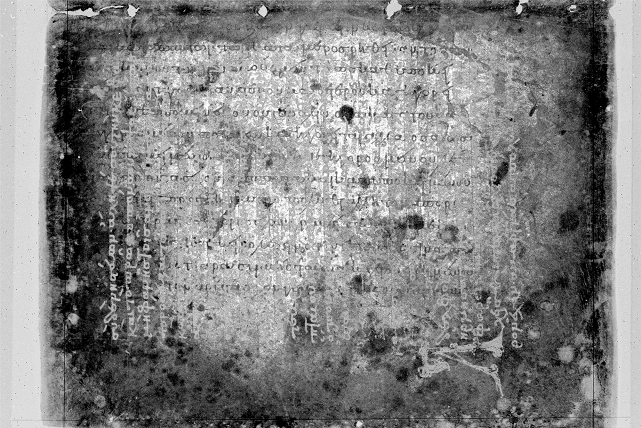

The Archimedes Palimpsest is [and I paraphrase] a Byzantine euchologion or prayer book manuscript, thought to have been completed by April 1229, and probably made in Jerusalem. Much of the parchment the scribes used in making the prayer book came from a earlier book of works by Archimedes, including his “On Floating Bodies” – a treatise of which no other copy survives. It seems the Archimedes manuscript dates back to tenth century Constantinople.

image credit: Archimedes Palimpsest Project

Erase Constantinople from your parchment, cut it and rotate it 90°, and you can build Jerusalem in its place. Peer deeply into prayer using multispectral imaging several hundred years later — and you may find combinatorial mathematics dating back more than two millennia…

What you are seeing in this image above is the workings of a mind two centuries BCE, transcribed in the tenth century CE, and made visible beneath and through other writing from the thirteenth, by twenty-first century tech.

So it is that Archimedes speaks to us today.

*

A palimpsest, then, is a layering of time on time, and the world we walk and talk in is itself a palimpsest.

The enduring, you might say, can be seen through the transient — the zebra crossing through the snow.

*

To see two times at once — to see history, accurately or otherwise, as a metaphor for today — is to see simultaneously.

As in Sergey Larenkov‘s celebrated photos, in which World War II and the present day coexist:

image credit: Larenkov, Wrecked tank “Tiger” in Tiergarten park

[ edited to add: Larenkov takes black and white photos from WW II, shoots the same scene in color from the same position today, and masterfully stitches them together digitally to create an image that allows the ghost of the past to seen in the present — brilliant! ]

Here again, as in the magically surreal sculptures of Nancy Fouts, we see the power of mapping one thing onto a kindred other of which Koestler wrote.

*

To tie all this back into the question of Which world is more vivid? This, or the next? — Stanley Hauerwas in his book, War and the American Difference: Theological Reflections on Violence and National Identity, suggests:

There is another world that is more real than a world determined by war: the world that has been redeemed by Christ.

He then clarifies his intent in saying:

The statement that there is a world without war in a war-determined world is an eschatological remark. Christians live in two ages in which, as Oliver O’Donovan puts it, “the passing age of the principalities and powers has overlapped with the coming age of God’s kingdom.” O’Donovan calls this the “doctrine of the Two” because it expresses the Christian conviction that Christ has triumphed over the rulers of this age by making the rule of God triumphantly present in the mission of the church. Accordingly the church is not at liberty to withdraw from the world but must undertake its mission in the confident hope of success.

*

Indeed, both Christianity and Zen would say that the greatest palimpsest is the palimpsest in which the transient circumstances of one’s life can all but obliterate the imperishable truth that underlies them — a palimpsest whose deepest layers may be read not with x-rays but by insight.

Christ lived in two times, or more accurately, time and eternity — to him the palimpsest was transparent, and thus he spoke (in John 8:58) what I suspect are the most profound five words in the Gospels:

Before Abraham was, I am.

Happy Easter!