The Sounds of Silence and Your Own Mind

Tuesday, November 27th, 2012

Scott Shipman had an excellent book review post An Unknown Future and a Doubtful Present: Writing the Victory Plan of 1941 — a review-lite and a few questions in which he discussed the intellectual seriousness and evolution of war planner Major Albert C. Wedemeyer as a military officer and strategist:

….Wedemeyer was an honor graduate of the Command and General Staff College, and his performance earned him the opportunity to attended the Kriegsakademie, the German staff college. However, coupled with impressive academic preparations, Kirkpatrick writes that Wedemeyer’s curiosity exposed him to a “kaleidoscope” of ideas and methods. Kirkpatrick summed-up Wedemeyer: “Competence as a planner thus emerged as much from conscientious professional study as from formal military education…” Going on to say:

In common with many of his peers, much of Wedemeyer’s professional and intellectual education was less the product of military schooling than of personal initiative and experience in the interwar Army.

Wedemeyer’s intellectual development was purposeful and paid off. In Wedemeyer’s deep study of his profession he used the prescribed paths, but also explored on his own. How common is that today?

As often happens, the discussion can take an unexpected turn in the comments section. Lexington Green weighed in with this:

Think about George Marshall in China, traveling around on horseback. No cell phone, no email. The man could actually think. Or Eisenhower meeting with Fox Connor to talk about the books Connor had him read. Telephone calls were not even common. The military might do well to have two days once a quarter of silent retreats, only emergency communication permitted, with literally no unnecessary conversation, for groups of officers and non-coms, with some assigned reading and some self-selected on the same theme, then an open discussion after dinner. It would cost virtually nothing and would be an intellectual and mental oasis, and some good ideas might come out of it. Religious silent retreats which last a couple of days and are truly life-restoring. This would probably be useful as well.

That in turn provoked this response from Marshall:

My sense is that many of us live, work, and fraternize in a culture of crisis. Everything is urgent. One response is to just shut off the moment we get some downtime. TV, drinking, schlock fiction, immersion in pop culture, video games, blog reading are some of the ways I’ve coped. I grew out of those as timewasters as I realized that I no longer had time to shut off if I wanted to do something.

But I still live in a culture of crisis. Almost everybody around me “has no time”. It doesn’t really matter what is being proposed, the sense of urgency kills all ambition toward progress. Defending myself and my space form this is a daily challenge – and some days I lose.

I’m visiting family this week on a long-scheduled “vacation” that has been interrupted by my office several times already, but always with the promise, “just this thing, Marshall, we don’t want to take you away from your family”. And these are the people I choose as my allies!

The culture of crisis doesn’t believe in people’s choices. It says that time will only be wasted, so we have to keep our people busy. After all, see how they spend their “free” time? Dissolute wastrels the lot of them. And then the culture of crisis tells us that we need to recharge by shutting off our minds. You need to vege out, man, you’re stressed; turn on the TV and have a beer, mate. Or else fire up your e-mail and write six more. And, hey, sorry about your insomnia, but it lets you get a jump on the day, amirite? [….]

The discussion moved on, but I have been mulling upon this exchange ever since.

The first thing that came to mind is that what we mean by “silence” really isn’t silent, what is really meant is that there is an absence of human voice pulling at our limited capacity for attention. Cognitive load is probably a real, if variable, limit on human cognition and the nature of hyperconnected information society is that all too frequently we are -and feel – “overloaded”.

When human voices are absent the “background” environmental noise comes “forward” , natural (wind through trees, animals etc) or mechanical (various humms and clicks) that we unconsciously tune out as a matter of routine focusing on conversation or distracting hearsay, broadcasts and so on. The processing in the brain is significantly different depending on what kinds of sounds you are listening to, for example:

1. Listening to Music

2. Listening to Language

3. Listening to unpleasant sounds (nails on chalkboard etc.)

So eliminating human speech from your environment but not hearing (earplugs) itself allows other regions of your brain to become more active than usual, depending on whatever else you may be doing at the time (walking, chopping wood, smelling a flower, scanning the horizon and so on). Your brain’s performance and how it varies when thinking under conditions of different combinations and levels of sensory stimuli – “crossmodal processing” – is not yet well understood as research is in early stages of investigation.

I will speculate here that what is important for enriching your thinking is that taking your brain out a linguistic-saturated environment (let’s include the “soundless noise” of intruding textual symbols as well from smartphones, iPads, laptops) gives it an opportunity to operate differently for a time and establish new neuronal network patterns of activity. Various forms of meditation – which involves both silence and an intentional modulation of attention – also alters normal brain activity.

I will now go further out on a data-free analytical limb and hypothesize that making a practice of “silence” and/or meditation might improve your thinking by making moments of creative insight more likely. Studies on insight tend to show that as a cognitive event, insight comes about as a kind of a “pulse” of activity and relaxation in the brain:

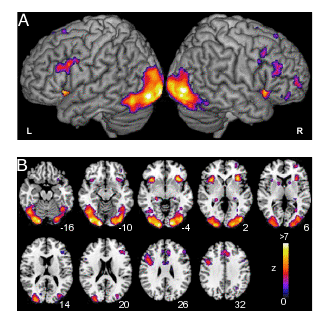

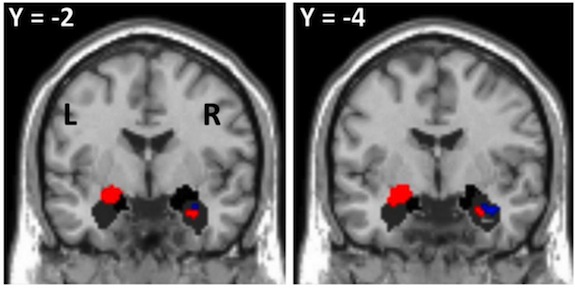

….Mark Jung-Beeman, a cognitive neuroscientist at Northwestern University, has spent the past fifteen years trying to figure out what happens inside the brain when people have an insight. Jung-Beeman became interested in the nature of insight in the early nineteen-nineties, while researching the right hemisphere of the brain. Mentions Jonathan Schooler. Jung-Beeman decided to compare word puzzles—or Compound Remote Associate Problems (C.R.A. Problems)—solved. He teamed up with John Kounios, a psychologist at Drexler University, and they combined fMRI and EEG (electroencephalography) testing to scan people’s brains while they solved the puzzles. The resulting studies, published in 2004 and 2006, found that people who solved puzzles with insight activated a specific subset of cortical areas. Although the answer seemed to appear out of nowhere, the mind was carefully preparing itself for the breakthrough. The suddenness of the insight is preceded by a burst of brain activity. A small fold of tissue on the surface of the right hemisphere, the anterior superior temporal gyrus (aSTG), becomes unusually active in the second before the insight. Once the brain is sufficiently focused on the problem, the cortex needs to relax, to seek out the more remote association in the right hemisphere that will provide the insight. As Kounios sees it, the insight process is an act of cognitive deliberation transformed by accidental, serendipitous connections. Mentions Joy Bhattacharya and Henri Poincaré. The brain area responsible for recognizing insight is the prefrontal cortex. Earl Miller, a neuroscientist at M.I.T., spent years studying the prefrontal cortex. He was eventually able to show that it wasn’t simply an aggregator of information, but rather it was more like a conductor, waving its baton and directing the players. In 2001, Miller and Princeton neuroscientist Jonathan Cohen published an influential paper laying out their theory of how the prefrontal cortex controls the rest of the brain. It remains unclear how simple cells recognize what the conscious mind cannot. An insight is just a fleeting glimpse of the brain’s huge store of unknown knowledge.

Another interesting data point to consider re: “silence” and insight is that the mental illness of schizophrenia, where delusions and other mental “noise” exists is significantly negatively correlated with insight. Researchers are currently investigating if meditation can ease the symptoms of schizophrenia and other mental illnesses.

For myself, I find my best ideas come via insight when I am doing something primarily physical requiring steady but not all of my concentration and I am alone – working out, walking the dog, a household chore and so on. Relatively useful ideas can happen when I am reading or writing or debating (i.e. interacting with a text or a person), but they tend to be analytic and derivative, sort of an intellectual “tweaking” or “tinkering” but not ones that are fundamentally creative or synthesizing.

Lexington Green may be right – Silence is golden.