[ by Charles Cameron — a tale of two films, two conflicts, two cities ]

.

Are these two positions — take one side, take both sides — reconcilable?

That’s the koan, the paradox that’s facing me, after seeing two terrific films by these two directors again, this time back-to-back. The two films their respective directors are discussing are Gillo Pontecorvo‘s Battle of Algiers and Anurag Kashyap‘s Black Friday.

Elie Weisel triggered this set of reflections for me when I saw his stark statement of the “one side” position:

We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.

Let’s turn to the films.

**

Pontecorvo’s Battle for Algiers is a rightly-celebrated classic, and it’s opening shot confirms the director’s claim to show compassion for both sides:

That’s an unexpected question from torturer to the victim he has just “broken”, and speaks volumes about the director’s intent — as does this quote from the french paratroop commander, Col. Mathieu, speaking of Larbi Ben M’Hidi, a leader of the National Liberation Front (FLN) whom he has captured and questioned — and who in “RL” was in fact murdered, though his death was reported at the time as a suicide:

Pour ma part, je peux seulement vous dire que j’ai eu la possibilité d’apprécier la force morale, le courage et la fidélité de Ben M’Hidi en ses propres idéaux. Pour cela, sans oublier l’immense danger qu’il représentait, je me sens le devoir de rendre hommage à sa mémoire.

For my own part, I can only tell you that I had the opportunity to appreciate Ben M’Hidi’s moral strength, his courage and his loyalty to his own ideas. On that account, and without overlooking the immense danger he represented, I feel obliged to salute his memory.

That reads to me as the respect of courage for courage.

The Pentagon, FWIW, held a screening of Battle for Algiers in September 2003, issuing a flyer indicating their reason to be interested in the film:

How to win a battle against terrorism and lose the war of ideas. Children shoot soldiers at point-blank range. Women plant bombs in cafes. Soon the entire Arab population builds to a mad fervor. Sound familiar? The French have a plan. It succeeds tactically, but fails strategically. To understand why, come to a rare showing of this film.

Yes indeed, it does sound a tad familiar.

**

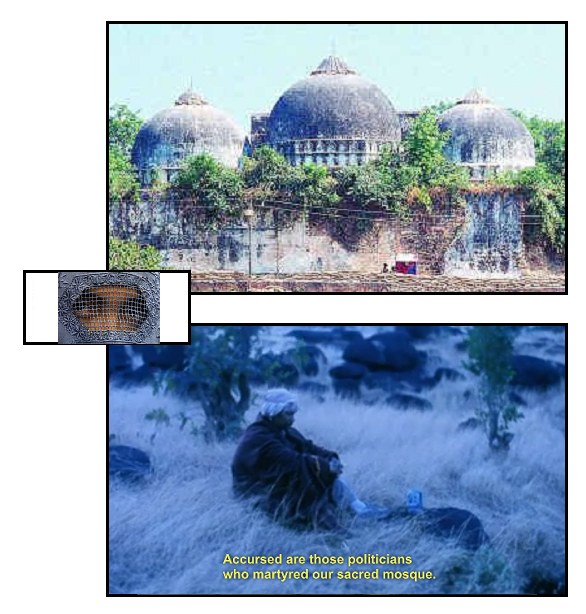

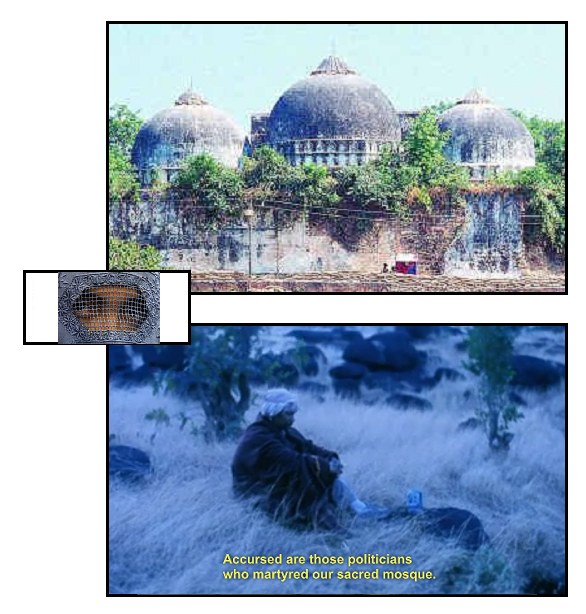

I’ll represent Kashyap’s Black Friday visually with a pair of images, the top one showing the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya / Oudh, which was leveled in December 1992 by an angry Hindu mob who claimed it had been built on the birthplace of Lord Rama, the avatar of Vishnu whose story is told in the Mahabharata —

while the lower one represents Muslim rage at that event, making use of voice-over and that remarkable phrase, “martyred our sacred mosque”, to good effect.

Kashyap, then, can understand the feelings behind the horrific series of terrorist bombings that shook Bombay — as well as those of the bombed and terrorized population of that city. As Oorvazi Irani explains in her commentary on the film, Kashyap’s own views are expressed in the voice of DCP Rakesh Maria in the “chapter” on the interrogation of Badshah Khan:

Badshah Khan very proudly takes credit for the bombings and says Muslims have taken the revenge for the atrocities done to their Muslim brothers. That’s when Kay Kay Menon who plays the cop says and speaks in the voice of the director “…Allah was not on your side, on your side was Tiger Memon. He saw your rage and manipulated you. He was gone before the first bomb was even planted. ..he fucked you over. you know why? Because you were begging for it. All in the name of religion. You are a fucking idiot. You are an idiot and so is every Hindu, who murders one of you. Everyone who has nothing better to do … but to fight in the name of religion is a fucking idiot.”

**

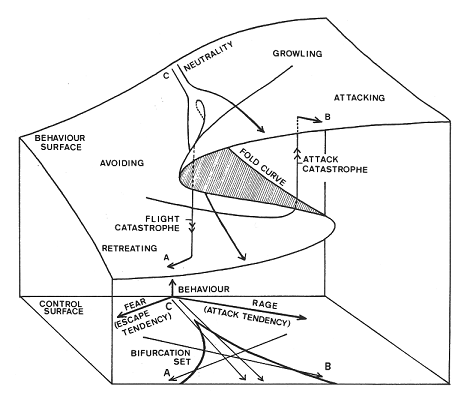

Can there be a right side and a wrong side in a game? There can certainly be a winning side and a losing side — but a right side and a wrong side?

I ask, because the connection between wars and games is an ancient one. Can there be a right side and a wrong side in war? Looking at World War II, which was almost certainly the war that Elie Weisel was thinking of, the answer is pretty obviously yes. But what about the reasons given for “our side” being the right side?

Is our cause just because God is on our side? Because might makes right, and the big battalions are on our side? Or simply because it is our side — my country, right or wrong?

And then there is civil war to consider — for all wars are civil wars, when seen within the context of that greater “nationality”, the human race.

Abraham Lincoln, from his Second Inaugural:

Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came. … Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. … The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes…

The whole issue of the just war — or of jihad, its Islamic approximate equivalent — revolves around the question of whether there can be a wrong side in war.

**

If there can be a wrong side, it may be shredded. As Mark Twain once prayed:

O Lord our Father, our young patriots, idols of our hearts, go forth to battle — be Thou near them! With them — in spirit — we also go forth from the sweet peace of our beloved firesides to smite the foe. O Lord our God, help us to tear their soldiers to bloody shreds with our shells; help us to cover their smiling fields with the pale forms of their patriot dead; help us to drown the thunder of the guns with the shrieks of their wounded, writhing in pain; help us to lay waste their humble homes with a hurricane of fire; help us to wring the hearts of their unoffending widows with unavailing grief; help us to turn them out roofless with little children to wander unfriended the wastes of their desolated land in rags and hunger and thirst, sports of the sun flames of summer and the icy winds of winter, broken in spirit, worn with travail, imploring Thee for the refuge of the grave and denied it — for our sakes who adore Thee, Lord, blast their hopes, blight their lives, protract their bitter pilgrimage, make heavy their steps, water their way with their tears, stain the white snow with the blood of their wounded feet! We ask it, in the spirit of love, of Him Who is the Source of Love, and Who is the ever-faithful refuge and friend of all that are sore beset and seek His aid with humble and contrite hearts. Amen.

**

There are things to be said for being on the winning side of a conflict: you get to write history. There may be things to be said for being on the losing side: you gain the sympathy that accrues to the underdog. There are things to be said for supporting neither side, for being on the sidelines to pick up the pieces.

Then again, as Buddha observed in the Dhammapada, there are disadvantages to being on either side —

Victory breeds hatred. The defeated live in pain. Happily the peaceful live giving up victory and defeat.

while Christ muddies the simplicity of the whole business with a further contrarian note:

love your enemies.

Peace is not a bad side to be on, but perhaps love is more nuanced.

**

To bring us full circle, here’s another statement of the Elie Weisel position, this time in the words of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the Lutheran pastor and theologian involved in the plot to assassinate Hitler and executed in one of the concentration camps — together with a response to the question I’ve been posing for myself here which may perhaps providinge some measure of reconciliation, this one from a contemporary Zen Buddhist, someone for whom the appreciation of koans is a way of life: