Of images and likenesses

Thursday, May 30th, 2013[ by Charles Cameron — a storm in a tea-kettle, various resemblances to Hitler, how Pudovkin perceived and practiced montage, what happened when the talkies came along, and four faces of Christ ]

.

It begins with something as innocent ad a tea kettle:

Does this otherwise innocuous tea kettle resemble Hitler? Does it look enough like Hitler to merit JC Penney withdrawing it from sale?

**

Let’s take a look at a couple of other “resemblances to Hitler”:

Who most resembles Hitler — Chaplin, or Stalin?

On the face of it, that’s an easy question. If I were to just ask you the question “who is most like Hitler” in words, you might very well say Stalin, or Pol Pot perhaps — or, I suppose, if you were very focused on World War II and the Axis leaders, Mussolini.

And if I asked you “who looks most like Hitler?” you might well say Charlie Chaplin — but you’d be “thinking visually” in terms of appearances, rather than “verbally” in terms of meanings.

So there are at least two different ways someone can resemble Hitler — in terms of appearance, and in terms of behavior.

**

We don’t notice our own noses most of the time, even though they’re within our field of vision — and it’s a bit like that with likeness. We don’t have a grammar of resemblance, and that’s part of what I want to explore here, in drawing your attention to these two ways (at least) in which we can think of someone resembling Hitler.

Placing two pictures side by side — Charlie Chaplin and Hitler, Hitler and Joseph Stalin — gets us to think a bit about the parallelisms and oppositions. And that’s a large part of what my DoubleQuotes format is good for. I am interested in what the mind does with juxtapositions, and I’m interested in getting us able to hold two contrasting thoughts in mind at the same time. As F Scott Fitzgerald said:

The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.

I’m in two minds as to whether he’s right, of course.

**

So montage. So the beginnings of Russian cinema, and the great directors of the silent era in film, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Sergei Eisenstein.

Pudovkin wrote quite a bit about montage, about what he called relational editing, telling us:

editing is not merely a method of the junction of separate scenes or pieces, but is a method that controls the “psychological guidance” of the spectator.

He talked about five modes of editing, getting close to the foundations of a grammar of resemblance of the kind I mentioned above — contrast, paralleliem, symbolism, simultaneity and leit-motif. He said, for instance:

Suppose it be our task to tell of the miserable situation of a starving man; the story will impress the more vividly if associated with mention of the senseless gluttony of a well-to-do man.

and went on:

it is possible not only to relate the starving sequence to the gluttony sequence, but also to relate separate scenes and even separate shots of the scenes to one another, thus, as it were, forcing the spectator to compare the two actions all the time, one strengthening the other.

Under the heading of Symbolism, he noted:

In the final scenes of the film Strike the shooting down of workmen is punctuated by shots of the slaughter of a bull in a stockyard. The scenarist, as it were, desires to say: just as a butcher fells a bull with the swing of a pole-axe, so, cruelly and in cold blood, were shot down the workers.

I don’t suppose I’m alone in thinking here of the ending of Coppola‘s Apocalypse Now — and I doubt Coppola would have been unaware of the tribute he was paying to one of the early masters of cinematography, either. And what doe Pudovkin say about the symbolic editing together of the shooting of workmen punctuated by the slaughter of a bull?

This method is especially interesting because, by means of editing, it introduces an abstract concept into the consciousness of the spectator without use of a title.

**

All this, of course, during the silent era. And when the talkies begin…

After the advent of the talking pictures, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Alexandrov and Vertov issue a statement, attempting to salvage the emotional impact of montage which is in danger of being capsized by the oh so new and glittery charm of verbals — of people talking:

Only a contrapuntal use of sound in relation to the visual montage piece will afford a new potentiality of montage development and perfection.

The first experimental work with sound must be directed along the line of its distinct nonsynchronization with the visual images. And only such an attack will give the necessary palpability which will later lead to the creation- of an orchestral counterpoint of visual and aural images

You see what’s going on here? Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Vertov want the mind to be working on two tracks of ideation at once — a visual track, full of emotional impact, and a verbal track, in counterpoint to the visual.

They want us to be able “to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time” — not in synchrony but in counterpoint.

So this business of juxtaposition, of contrapuntal thinking, goes quite deep, and it’s my contention that it’s a skill we need both to develop and to understand — hence my interest in building a grammar of resemblance, of rhyme, of fugue, of graphic match, of equation.

**

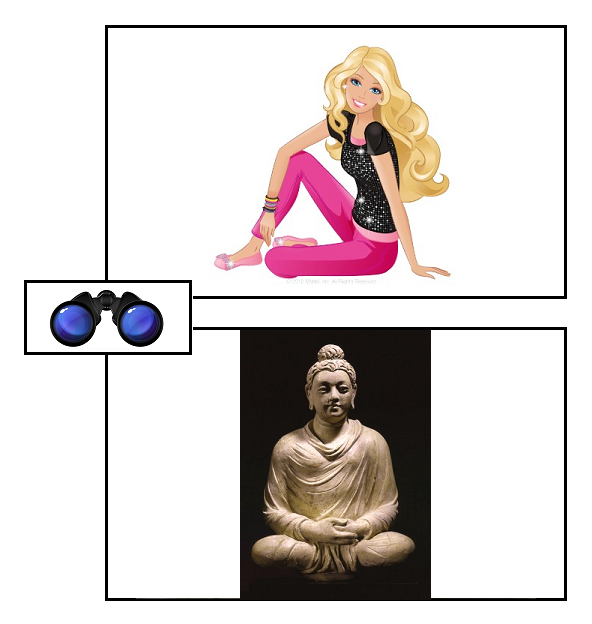

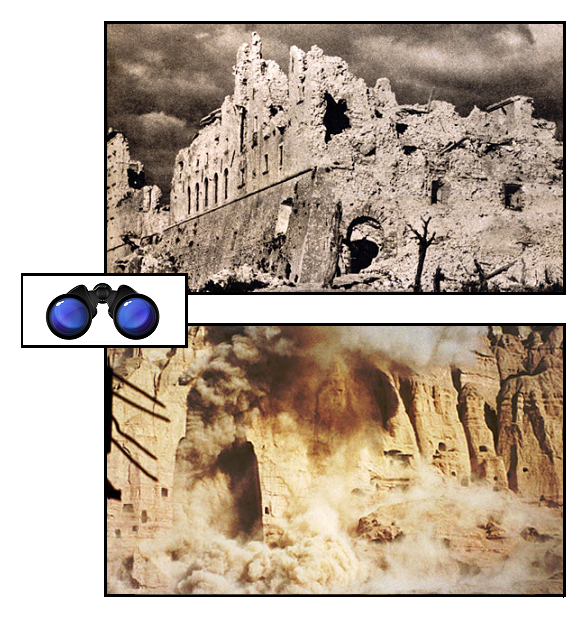

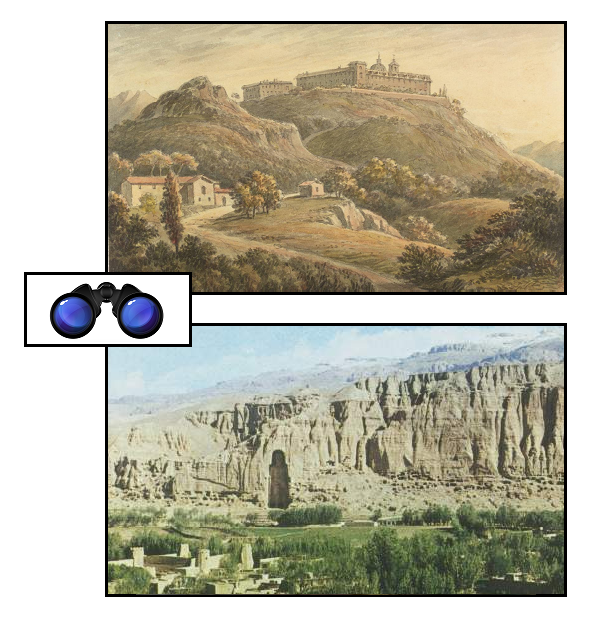

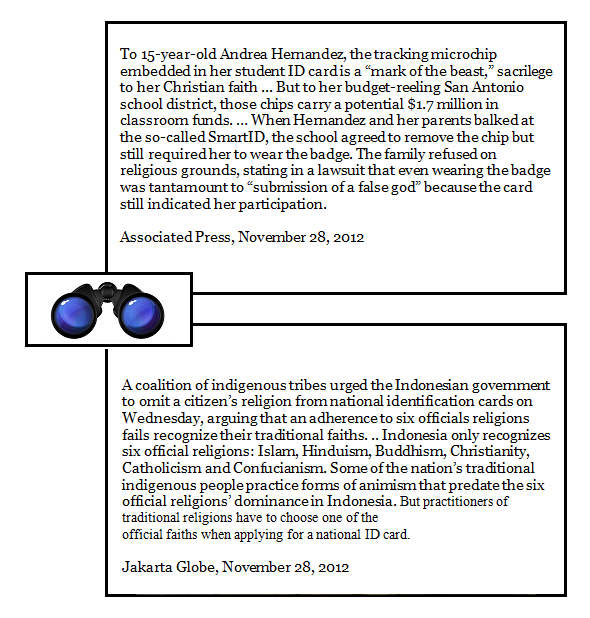

One final example. If the “likeness of Hitler” example confronted us with the “nature of likeness” as between facial resemblance and similarities of behavior, this next instance will deal more with “evidence of likeness”:

Here’s the question: are these “real” likenesses?

**

The two likenesses above are both of interest as possible “likenesses of Christ” — the top one taken from the Shroud of Turin, the lower one allegedly photographed in the snow, perhaps in China. The image on the Shroud might be a sort of “photographic negative” of the actual face of man a crucified two thousand years ago — and scientific techniques may or may not offer us evidence as to that likelihood. The other image — supposedly of the face of the same Christ, this time seen and recognized by a photographer in shadows on snow — how does one check the provenance of an image like that?

We don’t have a photographic record of what Christ looked like to compare our own images with — unless the Shroud turns out to offer us just that — so it’s likely we’re back at the distinction first drawn by theologians over a century ago, between “the Jesus of History” and “the Christ of Faith”.

Consider the two images below, neither one perhaps what a camera might have seen if a photographer could time-travel back two thousand years, but each suited to the people for whom it was produced — in China, in Africa:

The Christs these two images evoke come from a different mode of seeing to the images captured in biometric scans and on ID cards — yet they are well-suited for devotion and inspiration…