[ by Charles Cameron — Farrall and McCants, debate and discourse]

.

.

There’s a whole lot to be learned about jihad, counter-terrorism, scholarship, civil discourse, online discourse, and social media, and I mean each and every one of those, in a debate that took place recently, primarily between Leah Farrall and Will McCants.

Indeed, Leah still has a final comment to make — and when she makes it, that may be just the end of round one, if I may borrow a metaphor from a tweet I’ll quote later.

.

1.

Briefly, the biographies of the two main agonists (they can’t both be protagonists, now, can they? I believe agonist is the right word):

Dr. Leah Farrall (left, above) is a Research Associate at the University of Sydney’s United States Studies Centre (USSC). She was formerly a senior Counter Terrorism Intelligence Analyst with the Australian Federal Police (AFP), and the AFP’s al Qaeda subject matter specialist. She was also senior Intelligence Analyst in the AFP’s Jakarta Regional Cooperation Team (JRCT) in Indonesia and at the AFP’s Forward Operating Post in response to the second Bali bombings. Leah has provided national & international counter terrorism training & curriculum development. She recently changed the name of her respected blog. Her work has been published in Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy, The Atlantic, and elsewhere.

Dr. William McCants, (right) is a research analyst at the Center for Strategic Studies at CNA, and adjunct faculty at Johns Hopkins University. He has served as Senior Adviser for Countering Violent Extremism at the U.S. Department of State, program manager of the Minerva Initiative at the Department of Defense, and fellow at West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center. He edited the Militant Ideology Atlas, co-authored Stealing Al Qa’ida’s Playbook, and translated Abu Bakr Naji‘s Management of Savagery. Will has designed curricula on jihadi-inspired terrorism for the FBI. He is the founder and co-editor of the noted blog, Jihadica. He too has been published in Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy, The Atlantic and elsewhere.

.

2.

Gregory Johnsen, the Yemen expert whose tweets I follow, noted:

Watching @will_mccants and @allthingsct go at it, is like watching heavyweights spar for the title about 17 hours

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross commented on the civility of the exchanges:

it was an excellent model of argument within this sphere. Competitive analysis is important, and it is generally best when conducted in the open, as this has been. Further, the exchange has been respectful and collegial, something that is atypical for today’s debates.

Between those two comments, you have the gist of why this debate is significant — both in terms of topic and of online conduct.

.

3.

The debate started with a blog post by Leah, went to Twitter where the back and forth continued for several days, was collated on Storify, received further exploration on several blogs, turned sour at the edges when an article on Long War Journal discussing Leah’s original blog post draw some less than civil and less than informed drive-by remarks in its comments section, and continues…

And to repeat myself: all in all, the debate is informative not only about its topics — issues to do with terrorism and targeting — but also in terms of what is and isn’t possible in online dialog and civil discourse on the web.

.

4.

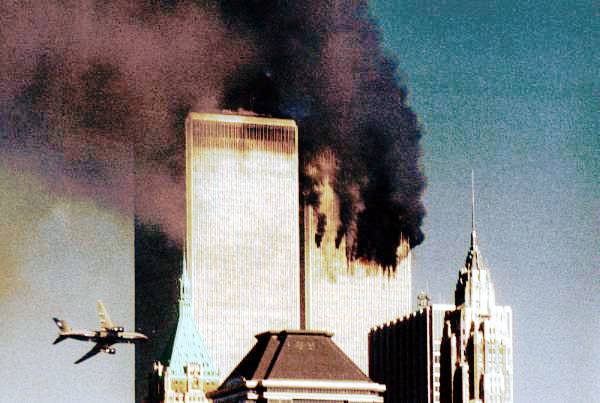

Leah Farrall’s Some quick thoughts on reports Abu Yahya al-Libi has been killed was the counter-intuitive (but perhaps highly intuitive) blog post which began the debate, and perhaps her key paras were these:

And if he has in fact been killed, I wonder if those who think this is a victory (and those supporting the strategy of extrajudicial killings more generally) have given ample thought to the fact that he along with others who have been assassinated were actually a moderating force within a far more virulent current that has taken hold in the milieu. And yes, given his teachings I do note a certain irony in this, but sadly, it’s true.

What is coming next is a generation whose ideological positions are more virulent and who owing to the removal of older figures with clout, are less likely to be amenable to restraining their actions. And contrary to popular belief, actions have been restrained. Attacks have thus far been used strategically rather than indiscriminately. Just take a look at AQ’s history and its documents and this is blatantly clear.

I say, “counter-intuitive” because, as Leah herself notes, this is not the received opinion — “Right now you’re probably scoffing at this” she writes. And I say intuitive because Leah may be the one here who whose insight comes from herself not the crowd, who sees things from a fresh angle because she has a more wide angle of vision, who is in fact intuiting a fresh and revealing narrative…

Not that she’s necessarily right in this, and not that it would be the whole picture if she was — but that she’s challenging our orthodoxies, giving us food for thought — and then, having read her, we need to see how clearly thought out the response is, how strongly her challenge withstands its own challenges… how the debate unfolds.

.

5.

I am not going to summarize the debate here, I am going to give you the pointers that will allow you to follow it for yourselves.

It is very helpful indeed for those who are interested in this unfolding debate, that Khanserai has twice Storified the initial bout of tweets between Farrall and McCants.

Khanserai’s second Storify is the one to read first, as it offers the whole sweep of several days of tweeting. That’s the full braid. Khanserai’s earlier Storify is worth reading next. It concerned itself solely with Leah’s significant definitional distinctions regarding discriminate vs indiscriminate targeting and targets vs victims.

There’s a lot to read and even more to mull right there, but the persevering dissertation writer for whom this is the ideal topic will then want to read a number of significant posts triggered by the debate:

Jarret Brachman was among the first to comment on al-Libi’s reported demise, in a post titled In a Nutshell: Abu Yahya’s Death. I don’t know if his post appeared before or after Leah’s, but his comment is congruent with hers:

The cats that Abu Yahya and Atiyah had been herding for so long will begin to wander. They will make mistakes. They will see what they can get away with. Al-Qaida’s global movement cannot endure without an iron-fisted traffic cop.

I look forward to Brachman’s comments on al-Libi’s “other important role: that of Theological-Defender-in-Chief for al-Qaida”. Another day…

McCants’ On Elephants and Al-Qaeda’s Moderation posted on Jihadica first paraphrases Farall:

Leah argues that the US policy of killing senior al-Qaeda Central leaders is wrongheaded because those leaders are “a moderating force within a far more virulent current that has taken hold in the milieu.” Leah compares these strikes to the practice of killing older elephants to thin a herd, which leaves younger elephants without any respectable elder to turn to for guidance as to how to behave. By analogy, killing senior al-Qaeda Central leaders means there will be no one with enough clout to rein in the younger generation of jihadis when they go astray.

He then argues that while there “might be good reasons not to kill al-Qaeda Central’s senior leaders with drones but their potential moderating influence is not one of them” — and proceeds to enumerate and detail them. His conclusion:

It is hard to imagine a more virulent current in the jihadi movement than that of al-Qaeda Central’s senior leaders. Anyone with a desire or capability of moderating that organization was pushed out long ago. AQ Central may have moderated in how it conducts itself in Muslim-majority countries, but it certainly hasn’t moderated toward the United States, which is what has to be uppermost in the minds of US government counter-terrorism policymakers.

Other responses worth your attention — and I know we’re all busy, but maybe this is an opportunity to dig deeper something that shouldn’t only concern those in search of a dissertation topic — would include:

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross’s The Strategy of Targeting al Qaeda’s Senior Leadership posted at Gunpowder and Lead contains the most thoughtful counterpoint to Leah’s point that I have found:

contrary to Farrall’s argument, a strategic opponent actually seems far more dangerous than an indiscriminate opponent

Clint Watts should be read and pondered, too. His post, It’s OK to Kill Senior al Qaeda Members in Pakistan, tackles Leah’s position from several angles, one of which focuses on her “law enforcement” perspective on terror:

I am with Leah that in an ideal world, it would be great to capture, convict and imprison terrorists. This approach only works when there are effective criminal justice methods for implementing it.

I wonder how he views military vs law enforcement attempts to corner Joseph Kony, but that’s off topic. To return..

Bernard Finel, too, posted a thoughtful piece on The Unsatisfying Nature of Terrorism Analysis, and wrapped up his post with the words:

In short, I’ll keep reading Farrall, McCants, and GR because they are smart, talented folks. They know a lot more than I do. But I can’t help by feel that there just isn’t enough there to make their arguments convincing on a lot of scores.

Those are the heavyweights weighing in, as far as I can see — feel free to add others in the comments section. But then…

.

6.

But then there’s Andrew Sullivan in The Daily Beast, asking Are Drones Defensible? in what I found to be a lightweight contribution. As I read it, Sullivan’s key question is:

if you’d asked me – or anyone – in 2001 whether it would be better to invade and occupy Afghanistan and Iraq to defeat al Qaeda, or to use the most advanced technology to take out the worst Jihadists with zero US casualties, would anyone have dissented?

as if such a hypothetical — asking about popular opinion rather than ground realities, which are a whole lot more complicated either way — was the right question to be asking. And his conclusion, interesting but unsubtle: “drones kill fewer innocents”.

.

7.

Oh, lightweight is more or less okay in my book, as is the strong affirmation of a strong position.

The editors at Long War Journal clearly feel strongly about Leah’s suggestion, and make no bones about it in a post titled US killing moderate al Qaeda leaders, like Abu Yahya, says CT analyst — which I don’t think is quite what Leah was saying — and opens with the sentence “This is one of the more bizarre theories we’ve heard in a while.”

That, you’ll notice, is a pretty bluntly phrased attack on Leah’s ideas, not her person. But what follows is interesting.

In the comments section at LWJ we see comments like “I assume this young lady is paid for her thoughts. If so by whom? Is she the ACLU lawyer? If so when was her last interview with Abu Yahya al Libi” and “Leah Farrall is one of these many Peter Panners who form a loosely knit confederation of self identified intellectuals with little or no understanding of violence & of those presently arrayed against ‘us'”…

You don’t see comments like those on the other sites I’ve mentioned, and to my mind they show surface ignorance of the deep knowledge that informs the main participants on both sides — and perhaps as a corrollary, the absence of the civility that characterizes the debate as a whole.

.

8.

My own interest in terrorism / counterterrorism is explicitly limited to the ways in which theological drivers manifest, and while I read a fair amount about the broader issues into which theology enters, I’m no expert, humble and (inside joke) for the moment at least, more or less clean-shaven.

I am waiting for Leah Farrall’s response to the debate thus far, but have no expectation of being the best proponent of any of the positions or nuances involved: I leave that to the experts, and am glad they are on the case, every one of them.

Two broad context pieces that have caught my attention:

Francine Prose, Getting Them Dead in the NY Review of Books

Patrick B. Johnston, Does Decapitation Work?

For myself, then, the main point here is to acknowledge the knowledge and insights of those who know what I can only guess, or perhaps catch out of the corner of my eye. The second lesson: that there’s much to be found in Joseba Zulaika‘s book, Terror and Taboo: The Follies, Fables, and Faces of Terrorism.

Even a brief glimpse of the book when Leah mentioned it has convinced me once again that Zulaika’s is a voice worth attending to.

.

9.

But wait, I am a Howard Rheingold friend, I’m concerned with dialog and deliberation and decency in discourse, not just terrorism and CT — and here I have no need for disclaimers.

What I learn here is that attentive listening to all (the folks in the comments section included) brings knowledge, that incivility frequently accompanies ignorance, and — I hope you will forgive me going all aphoristic here — that nuance is an excellent measure of insight..

This is a debate to admire and follow.