[ by Charles Cameron — two performances of Cage’s 4’33” in the New York and London Times: an interlude in my review of Where the Heart Beats, with a brief meditation on contrapuntal listening ]

.

I began to review Kay Larson‘s Where the Heart Beats in a post here last week, and am not done yet.

**

London:

photo credit: Chris Harris for the London Times

In John Cage’s sound of silence… at Liverpool Street station [London Times, subscription required], Igor Toronyi-Lalic describes performing John Cage‘s silent work 4’33” in what Cage himself — but few others — would have recognized as a concert venue, London’s Liverpool Street Station:

My rendition isn’t going down well. “This is doing my head in!” groans a drunken West Ham supporter as he watches me at the piano outside Liverpool Street station. I hear shuffling. “I can’t dance to this,” someone shouts. The restlessness is in danger of turning to anger. And I probably should have guessed it would. Presenting a performance of one of the most controversial works of music yet written in a rowdy Central London station forecourt on a Friday night on a public piano (one of several that made up the City of London Festival’s Play Me, I’m Yours artwork) was always going to be ambitious.

The work itself is hardly over before it begins — again, a paradox Cage would have enjoyed:

At my Liverpool Street Station performance, there was a symphony of rush-hour noise: commuter patter, train announcements, drunken heckling and the screeching of taxis stopping to pick up fares. Not everyone appreciated the music in this.

“When’s he going to start?” asked one lady as I finished the final movement. Others felt like they’d been had. “I thought you were going to play,” they shouted.

There’s more, and if you can get past the pay-wall you should read it all. I’ll just quote one more snippet here, though, because it leads directly into one strand of the book that I’ll be discussing in Part III of my review of Larson’s book:

“Classical musicians don’t know about Cage. They don’t perform it. We aren’t taught it in schools,” Volkov says.

But, for visual artists, Cage is a revered figure, a key part of the 1950s and 60s New York arts scene and godfather to conceptual and sound art, a connection cemented by Cage’s 40-year creative relationship with his lifelong partner, the late choreographer Merce Cunningham. “Cage worked with Rauschenberg and Cunningham and, at Black Mountain College, he mainly taught music to artists,” observes Volkov, “So, today, in art schools, they teach Cage properly. They teach his ideas.”

**

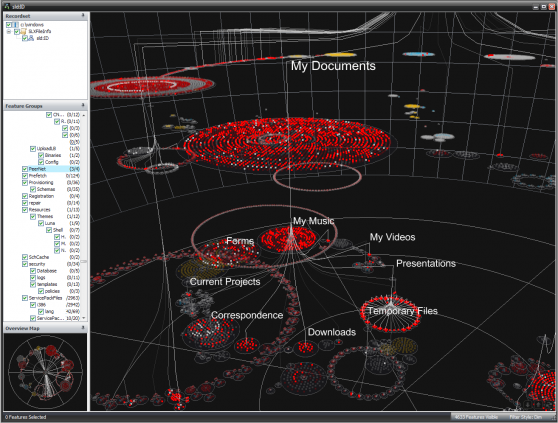

New York:

photo credit: Christian Hansen for the New York Times

From London’s Liverpool Street Station we pass to New York City’s subway system. I don’t know what it is about trains, but there you are and there you go. Or perhaps the transit is from Times to Times?

Allan Kozinn‘s John Cage Recital? Take the A Train [New York Times] starts by defining “Cage moments”:

You know about Cage moments, don’t you? We all have them, whether we think of them that way or not. They occur when happenstance kicks in, and surprising musical experiences take form, seemingly out of nowhere. They can happen anywhere at any time.

Listening. Listening as though all life is music.

Kozinn is a listener, a listener to music — but he doesn’t always listen for the music in his daily life. This time, as it happens, he did:

On the A train I wasn’t thinking about Cage at all. I had just heard an exquisitely turned, energetic performance of Schubert’s String Quintet in C at a church in Greenwich Village, and Cage could not have been further from my thoughts. Nor did the crowded subway car bring him to mind at first. But I noticed that it was unusually noisy.

**

Then something shifted:

Typically, most of the noise you hear comes from the subway itself: its din drowns out conversations, and people tend to stare at their feet, or at whatever they are reading, and listen to their portable music players. But this Tuesday evening just about all the people were talking, and working hard to drown out both the subway and the chats taking place around them.

I would normally have tuned all this out, but instead I sat back, closed my eyes and did what Cage so often recommended: I listened. I made no effort to separate the strands of conversation or to focus on what people were saying. I was simply grabbed by the sheer mass of sound, human and mechanical. It sounded intensely musical to me, noisy as it was, and once I began hearing it that way, I couldn’t stop.

Okay, this is where it get’s interesting. You remember that I pointed to the pianist Glenn Gould in my Said Symphony posts, and quoted this passage from David Rothenberg‘s Sudden Music:

Gould set himself up to hear the world in a new way. In diners he ate his lunch alone, eaves dropping closely on the voices around him. He learned to hear conversation as music, the lilting lines, the rhythms everywhere up, down, and around, what Bach does to our sense of talk. There are two part inventions in words, themes and variations in the quarrels of couples and the tales told by friends. Gould met the world on his own terms, and he was fascinated by this way of listening to human voices as if they were a musical interplay, not participating in a conversation but taking it all in, as an audience.

What Gould sets out to do — and records for Canadian Broadcasting — Kozinn finds himself doing:

Strand upon strand of the chatter was animated and midrange: there were neither basso profundos nor soaring sopranos in this choir, but after a moment the pitch levels began to sort themselves out as a kind of orchestration. Argumentative voices created driving, punchy rhythms that sailed over more smoothly floating narrative tones.

At least three languages were being spoken, each with its own melodic lilt and rhythmic character. To my left, a woman’s laughter momentarily changed the coloration of this vast choral tapestry and offset the argument to my right.

Within it all, squeaking metal yielded a high-pitched ostinato, and the ever-so-slightly-clattery rumble of the train was the high-tech equivalent of a Baroque basso continuo. As the train pulled into each station, the muted squeal of the brakes, the opening and closing of the doors and the slight shift in the balance of voices as some people left and others entered, already talking, suggested shifts between connected movements.

Again, I recommend reading the entire piece, but will close with just one more short clip:

I have heard “4’33” ” performed by pianists, percussion ensembles, oboists, cellists and orchestras, but none of those versions were as exciting as what I now think of as “4’33”: The Extended Subway Remix” by the A Train Yakkers, an ensemble so conceptual that its members had no idea they were in it.

Cage would have understood.

**

And wherever:

Listening — and listening to the world around us as music — can happen anywhere and everywhere. But as usual, I’d like to take this a step further.

As I never tire of repeating, Edward Said — pianist and music critic as much as writer on Israeli-Palestinian issues — carries the idea of listening to multiple voices a step further, when he suggests:

When you think about it, when you think about Jew and Palestinian not separately, but as part of a symphony, there is something magnificently imposing about it. A very rich, also very tragic, also in many ways desperate history of extremes — opposites in the Hegelian sense — that is yet to receive its due. So what you are faced with is a kind of sublime grandeur of a series of tragedies, of losses, of sacrifices, of pain that would take the brain of a Bach to figure out.

Said’s proposed manner of listening to the many voices of life in counterpoint involves listening to the words, their meanings, their stories, their histories, and thus to a simultaneous listening across time itself — not just to a harmonious blur, “Strand upon strand of the chatter .. a kind of orchestration .. driving, punchy rhythms that sailed over more smoothly floating narrative tones.”

It goes way deeper: my life and concerns, and yours, and yours, heard together — separate and interwoven — in polyphony, in a many-voiced music — in counterpoint.

In conflict, and in hope of resolution.