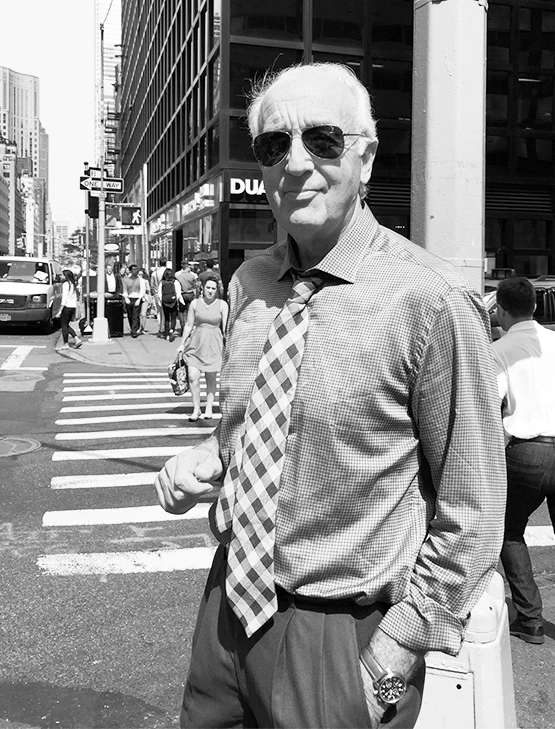

Review – The Artist’s Journey by Steven Pressfield

August 13th, 2018[mark safranski / “zen“]

The Artist’s Journey: The Wake of the Hero’s Journey and the Lifelong Pursuit of Meaning by Steven Pressfield

“Our aim is to make ourselves masters, not just of our craft but also of ourselves”

Novelist Steven Pressfield, having achieved critical success as author of bestseller fiction with such titles as Gates of Fire, The Legend of Bagger Vance, Killing Rommel and The Profession has long been keen on sharing the secrets of his success with aspiring writers. This led in turn to Pressfield’s emergence as a writer of non-fiction beginning with his highly recommended The War of Art and continuing with Do the Work, Turning Pro, The Authentic Swing and Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t. The specific emphasis in these books varied but the overarching goal was for Pressfield to help his readers become writers, real professional writers who could wrestle with their inner enemy of creativity, “Resistance” and emerge victorious.

While The Artist’s Journey continues in that vein, in it we see Pressfield’s evolution not just as a writer but as a thinker and teacher. Where previous books had examples were almost entirely granular and biographical The Artist’s Journey has a more meta feel, going more toward the roots of human creativity that undergird novelists, poets, musicians, painters and even scientists. It seemed, at least to me, in reading The Artist’s Journey that some of the introspection present in The Knowledge and the panoramic epic conflict in The Lion’s Gate, his novelized history of the Six Day War, have impacted Pressfield’s ideas about the importance of theme and imagination in human understanding.

Organized into staccato chapters reminiscent of a Stoic’s handbook, The Artist’s Journey borrows from the concept “the hero’s journey” and the monomyth theories of seminal literary scholar Joseph Campbell. To Pressfield, the artist is the returned hero. Having conquered, returning home bearing gifts for the people, the adventure has only just begun. The trials of the hero’s journey were the necessary rehearsal for becoming an artist.

An artist has a subject, a voice, a medium, a point of view and a style in touch with their generation or zeitgeist but Pressfield argues that the artist’s journey is to get in touch with or access their “muse” – their unconscious (“superconscious”) awareness which will be a more certain guide and open the doors of imagination. It’s an iterative relationship with the conscious mind:

“Monet like every artist was working simultaneously on both planes.

On the Dionysian he could see in his mind’s eye exactly how sunlight bounced off the curvilinear perimeter of a lily pad. On the Apollonian he was thinking “if I apply double thick blob of gentian violet with a medium pallet knife and twist it left handed so that the weightiest section of the blob accretes on the right side, then studio daylight reflecting off that in juxtaposition to the 40/60 mixture of puce and fuscia of the adjacent blob, should create the exact illusion I’m seeking”

I found this duality of mind concept interesting because Pressfield has distilled down and solidified an idea he’s been thinking about for some time. Back in 2009, Steve wrote to me here about his beliefs on creative thinking:

In my experience, the writing process bounces back and forth between two poles. One is the let-‘er-rip mode, which could be called “flow,” or “Dionysian.” That’s the one when the Muse possesses a writer and he just goes with it. But yes, as you suggest, it can lead you astray. It’s the like the great ideas you have at three in the morning after two too many tequilas. This mode has to be balanced by a saner-head mode, which sometimes to me almost feels like a different person–an editor, a reviser. That’s really when you put yourself in imagination in the place of the reader and ask yourself, as you’re reading the stuff that this “other guy” wrote: “Does this make any sense? Is this any good? Have I got it in the right place, in the right form? Should I cut it, expand it, modify it, dump it entirely.” Then you become cold-blooded and professional. You get ruthless with your own work. This is the time, I think, when “formula” wisdom can help, when you can ask yourself questions like, “What is my inciting incident?” or “What is my Act Two mid-point.” Not when you’re in the flow, or you’ll censor yourself and second-guess yourself. But now, when you’re rationally evaluating what you produced when you were in flow. This back-and-forthing, I imagine, would be true in any artistic or entrepreneurial venture. It’s great to let it rip and really get down some wild, skatting jazz riffs. But then we have to come back and ask ourselves, “Is this working for the audience? Is this working for the work itself?”

Pressfield devotes a great deal of space to the mediation between the rational and the intuitive, the conscious and unconscious, the material and the “higher realm” in imaginative creativity and it’s connection to the artist’s “voice” or self. By my rough estimate, 45 pages are spent on this topic alone and Pressfield, like Campbell, draws upon the ideas of the great psychoanalyst Carl Jung as well as tenets from Jewish mysticism, Zen Buddhism, William Blake and Aldous Huxley to elucidate this critical relationship. Pressfield writes:

Have you ever observed your mind as you write or paint or compose?

I have watched mine. Here’s what I see:

I see my awareness shuttle back and forth, like the subway between Times Square and Grand Central Terminal, from my conscious mind to my unconscious, my superconscious.

….The process is to me one of those everyday miracles, simultaneously mind bending in its implications and as common as dirt. Like the act of giving birth, it is at the same time miraculous and everyday.

This paradoxical explanation resonates with the views of experts on the functioning of the creative mind. Kyna Leski visualized and theorized the creative process as being akin to a thunderstorm. Sir Ken Robinson describes creativity as accessing “alternative ways of seeing, thinking and doing” while being “essentially human”. E. Paul Torrance, the researcher who did more than any other figure to investigate and measure the characteristics of creative thinking as a scientific process admitted “Much of it is unseen, nonverbal and unconscious. Therefore, even if we had a precise concept of creativity, I am certain we would have difficulty putting it into words.” In finding comfort for the artist in the ambiguity and contradictions of creativity, Steven Pressfield finds himself in good company.

The Artist’s Journey is not the same kind of book for aspiring writers as some of Pressfield’s previous works. For those struggling with the question of “Can I?” or the skills and practicalities of earning a living as a writer would be better served turning to The War of Art and Turning Pro. But for those who are on the way in a creative field and struggle with their footing with artistic vision or finding confidence in the integrity of their voice, The Artist’s Journey is both a guidepost and hymnal.