[by Mark Safranski, a.k.a. “zen“]

A Facebook friend with an astute comment pointed me toward this Wall Street Journal article by Joe Rago on the mission of General John Allen, USMC as “Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Counter ISIL”. What is a “Special Presidential Envoy” ?

In diplomatic parlance, a special envoy is an official with full powers (a “plenipotentiary”) to conduct negotiations and conclude agreements, but without the protocol rank of ambassador and the ceremonial duties and customary courtesies. A special envoy could get right down to business without wasting time and were often technical experts or seasoned diplomatic “old hands” whom the foreign interlocuter could trust, or at least respect. These were once common appointments but today less so. A “Special Presidential Envoy” is typically something grander – in theory, a trusted fixer or VIP to act as superambassador , a deal-maker or reader of riot acts on behalf of the POTUS. Think FDR sending Harry Hopkins to Stalin or Nixon sending Kissinger secretly to Mao; more recent and less dramatic examples would be General Anthony Zinni, USMC and former Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell.

In practice, a presidential special envoy could also be much less, the foreign policy equivalent of a national commission in domestic politics; a place to park thorny, no-win, political headaches the POTUS wants to ignore by creating the illusion of action and get them off the front pages. The position is really whatever the President wishes to make of it and how much power and autonomy he cares to delegate and what, if anything, he wishes the Special Envoy to achieve. Finally, these appointments are also a sign the President does not have much confidence or trust in the bureaucracy of the State Department or DoD, or their respective Secretaries, to carry out the administration’s policy. I wager that this is one of the reasons for General Allen’s appointment.

This means that General Allen is more or less stuck with whatever brief he was given, to color within the lines and make the best uses of any carrots or sticks he was allotted ( in this micromanaging administration, probably very little of either). Why was he chosen? Most likely because the United States sending a warfighting Marine general like Allen ( or a high CIA official) will always concentrate the minds of foreigners, particularly in a region where the US has launched three major wars in a quarter century. If not Allen, it would have been someone similar with similar results because the policy and civilian officials to whom they would report would remain the same.

So if things with ISIS and Iraq/Syria are going poorly – and my take from the article is that they are – the onus is on a pay grade much higher than General Allen’s.

I will comment on a few sections of the interview, but I suggest reading the article in full:

Inside the War Against Islamic State

Those calamities were interrupted, and now the first beginnings of a comeback may be emerging against the disorder. Among the architects of the progress so far is John Allen, a four-star Marine Corps general who came out of retirement to lead the global campaign against what he calls “one of the darkest forces that any country has ever had to deal with.”

ISIS are definitely an bunch of evil bastards, and letting them take root unmolested is probably a bad idea. That said, they are not ten feet tall. Does anyone imagine ISIS can beat in a stand-up fight, say, the Iranian Army or the Egyptian Army, much less the IDF or (if we dropped the goofy ROE and micromanaging of company and battalion commanders) the USMC? I don’t. And if we really want Allen as an “architect” , make Allen Combatant Commander of CENTCOM.

Gen. Allen is President Obama ’s “special envoy” to the more than 60 nations and groups that have joined a coalition to defeat Islamic State, and there is now reason for optimism, even if not “wild-eyed optimism,” he said in an interview this month in his austere offices somewhere in the corridors of the State Department

Well, in DC where proximity to power is power, sticking General Allen in some broom closet at State instead of, say, in the White House, in the EOB or at least an office near the Secretary of State is how State Department mandarins and the White House staff signal to foreign partners that the Presidential Special Envoy should not be taken too seriously. It’s an intentional slight to General Allen. Not a good sign.

At the Brussels conference, the 60 international partners dedicated themselves to the defeat of Islamic State—also known as ISIS or ISIL, though Gen. Allen prefers the loose Arabic vernacular, Daesh. They formalized a strategy around five common purposes—the military campaign, disrupting the flow of foreign fighters, counterfinance, humanitarian relief and ideological delegitimization.

The fact that there are sixty (!) “partners” (whatever the hell that means) and ISIS is still running slave markets and beheading children denotes an incredible lack of seriousness here when you consider we beat Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan and Fascist Italy into utter submission in the largest war in the history of the world with barely a third that number. The best that can be said here is that Allen, in trying to be a herder of cats, got them to graciously agree on letting the US set a reasonable list of open-ended operations and policy priorities.

Gen. Allen cautions that there is hard fighting ahead and victory is difficult to define….

I think my head is going to explode. I’m sure General Allen’s head is too because this means that President Obama and his chief advisers are refusing to define victory by setting a coherent policy and consequently, few of our sixty partners are anxious to do much fighting against ISIS. When you don’t know what victory is and won’t fight, then victory is not hard to define, its impossible to achieve.

At least we are not sending large numbers of troops to fight without defining victory. That would be worse.

Gen. Allen’s assignment is diplomatic; “I just happen to be a general,” he says. He acts as strategist, broker, mediator, fixer and deal-maker across the large and often fractious coalition, managing relationships and organizing the multi-front campaign. “As you can imagine,” he says, “it’s like three-dimensional chess sometimes.”

Or its a sign that our civilian leaders and the bureaucracies they manage are dysfunctional, cynical and incompetent at foreign policy and strategy. But perhaps General Allen will pull off a miracle without armies, authorities or resources.

Unlike its antecedent al Qaeda in Iraq, Islamic State is something new, “a truly unparalleled threat to the region that we have not seen before.” Al Qaeda in Iraq “did not have the organizational depth, they didn’t have the cohesion that Daesh has exhibited in so many places.” The group has seized territory, dominated population centers and become self-financing—“they’re even talking about generating their own currency.”

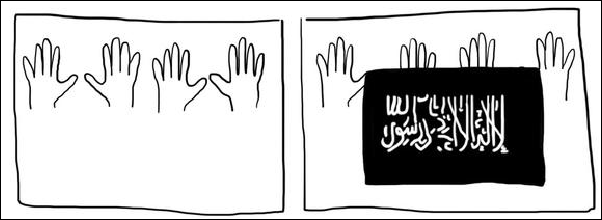

But the major difference is that “we’re not just fighting a force, you know, we’re fighting an idea,” Gen. Allen says. Islamic State has created an “image that it is not just an extremist organization, not just a violent terrorist organization, but an image that it is an Islamic proto-state, in essence, the Islamic caliphate.” It is an “image of invincibility and image of an advocate on behalf of the faith of Islam.”

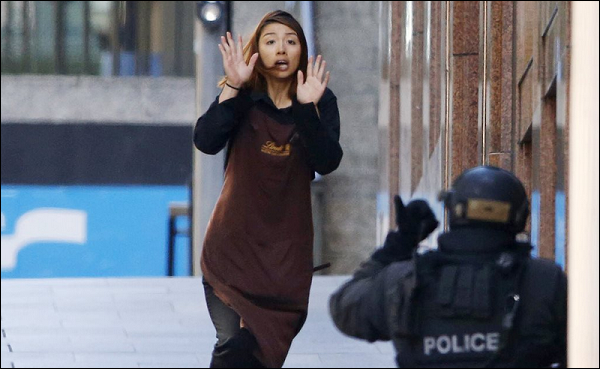

This ideology has proved to be a powerful recruiting engine, especially internationally. About 18,000 foreign nationals have traveled to fight in Iraq or the Syria war, some of them Uighurs or Chechens but many from Western countries like the U.K., Belgium, Australia and the U.S. About 10,000 have joined Islamic State, Gen. Allen says.

“Often these guys have got no military qualifications whatsoever,” he continues. “They just came to the battlefield to be part of something that they found attractive or interesting. So they’re most often the suicide bombers. They are the ones who have undertaken the most horrendous depredations against the local populations. They don’t come out of the Arab world. . . . They don’t have an association with a local population. So doing what people have done to those populations is easier for a foreign fighter.”

Except for the “never seen before” part – we have in fact seen this phenomena in the Islamic world many times before, starting with the Khawarijites, of whom ISIS are just the most recent iteration – this is all largely true.

ISIS, for all its foul brigandage, religious mummery and crypto-Mahdist nonsense is a competent adversary that understands how to connect in strategy its military operations on the ground with symbolic actions at the moral level of war. Fighting at the moral level of war does not always imply (though it often does) that your side is morally good. Sadly, terror and atrocities under some circumstances can be morally compelling to onlookers and not merely repellent. In a twisted way, there’s a “burning the boats” effect in openly and gleefully committing horrific crimes that will unify and reinforce your own side while daunting your enemies and impressing onlookers with your strength and ruthlessness. Men flocked to Spain to fight for Fascism and Communism. A remarkable 60% of the Nazi Waffen-SS were foreigners, most of whom were volunteers. Ample numbers of Western left-wing intellectuals were abject apologists not only for Stalin and Mao but the Khmer Rouge during the height of its genocide. ISIS atrocities and horror are likewise political crack for certain kinds of minds.

The problem is that none of this should be a surprise to American leaders, if they took their responsibilities seriously.

William Lind and Martin van Creveld were writing about state decline and fourth generation warfare twenty five years ago. We have debated 4Gw, hybrid war, complex war, LIC, terrorism, insurgency, failed states, criminal insurgency and terms more obscure in earnest for over a decade and have wrestled with irregular warfare since John F. Kennedy was president. Yet the USG is no closer to effective policy solutions for irregular threats in 2014 than we were in 1964.

A more hopeful sign is that the new Iraqi government is more stable and multiconfessional after the autocratic sectarian rule of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. His replacement, Haider al-Abadi, has been “very clear that the future of Iraq is for all Iraqis,” Sunni, Shiite and Kurd. He has restored relations with Middle Eastern neighbors and believes in the “devolution of power” across Iraq’s regions, Gen. Allen says. “Maliki believed in the centralization of power.”

So did we. Maliki and Hamid Karzai were originally our creatures. There was at least a bad tradition of centralization in Iraq, but we imposed it in Afghanistan ex nihilo because it suited our bureaucratic convenience and, to be frank, the big government technocratic political beliefs of the kinds of people who become foreign service officers, national security wonks, military officers and NGO workers. Unfortunately, centralization didn’t much suit the Afghans.

Critics of the Obama administration’s Islamic State response argue that the campaign has been too slow and improvisational. In particular, they argue that there is one Iraqi-Syrian theater and thus that Islamic State cannot be contained or defeated in Iraq alone. Without a coherent answer to the Bashar Assad regime, the contagion from this terror haven will continue to spill over.

Gen. Allen argues that the rebels cannot remove Assad from power, and coalition members are “broadly in agreement that Syria cannot be solved by military means. . . . The only rational way to do this is a political outcome, the process of which should be developed through a political-diplomatic track. And at the end of that process, as far as the U.S. is concerned, there is no Bashar al-Assad, he is gone.”

Except without brute force or a willingness to make any significant concessions to the states that back the Assad regime this will never happen. What possible incentive would Assad have to cooperate in his own political (followed by physical) demise? Our Washington insiders believe that you can refuse to both bargain or fight but still get your way because most of them are originally lawyers and MBAs who are used to prevailing at home by manipulation, deception, secret back room deals and rigged procedures. That works less well in the wider world which rests, under a thin veneer of international law, on the dynamic of Hobbesian political violence.

As ISIS has demonstrated, I might add.

The war against Islamic State will go on long after he returns to private life, Gen. Allen predicts. “We can attack Daesh kinetically, we can constrain it financially, we can solve the human suffering associated with the refugees, but as long as the idea of Daesh remains intact, they have yet to be defeated,” he says. The “conflict-termination aspect of the strategy,” as he puts it, is to “delegitimize Daesh, expose it for what it really is.”

This specific campaign, against this specific enemy, he continues, belongs to a larger intellectual, religious and political movement, what he describes as “the rescue of Islam.” He explains that “I understand the challenges that the Arabs face now in trying to deal with Daesh as an entity, as a clear threat to their states and to their people, but also the threat that Daesh is to their faith.”

While Iraqi and Iranian Shia have ample existentiall motive to fight ISIS. Sunni Muslims find ISIS brutality pretty tolerable, so long as it is far away from them personally and furthermore ISIS religious-theological lunacy is not terribly far removed from the extreme Salafi-Wahhabi version preached and globally proselytized by our good friends, the House of Saud – or exported violently by our other good friends, the Pakistani Army. Or at least Sunni Muslims are not bothered enough yet by ISIS to pick up arms and fight.

General Allen is doing his best at a herculean task, but American statecraft is broken and seduced by a political culture vested in magical thinking.