[ by Charles Cameron — on the necessary simultaneity of temporal and eternal perspectives ]

.

**

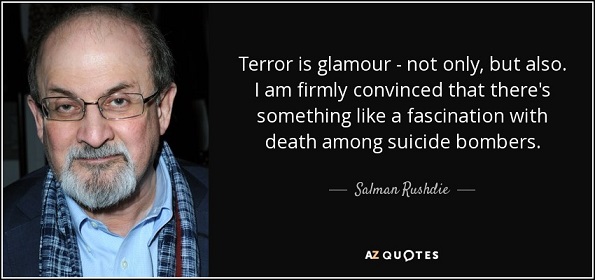

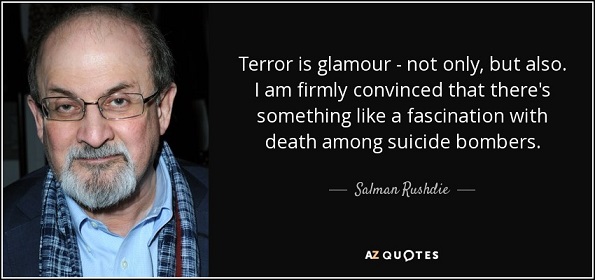

First as to glamour -– it may help to reflect that glamour, our word, comes not from Vogue but from the same origins as grammar (referring to languages) and grimoire (a book of spells, spelling also being a matter of language), and means something along the lines of “luminous illusion”. If we say terror is glamour, then, we mean that it “casts a spell” — and thus creates an appealing, indeed compelling, mirage. It lies, then, in the realm of magic, image, imagination, so ably delineated by Ioan Couliano in his great book, Eros and Magic in the Renaissance.

The best of contemporary advertising draws on precisely the same Renaissance principles of persuasion — principles of extraordinary power which we nowadays tend to dismiss as “magical thinking”.

**

Thus Virginia Postrel, in Terror Is Glamour:

Glamour can sell religious devotion or military glory as surely as it can pitch lipstick or island vacations. All promise a way to transcend our everyday circumstances, to experience more and become better than ordinary life allows. All invite us to imagine escape and transformation.

Postrel continues:

From Achilles and Alexander to “national greatness,” the glamour of battle is remarkably persistent. So is the glamour of martyrdom, as any trip through a Western museum or perusal of a Lives of the Saints (or its Protestant equivalent) will demonstrate. Nor is martyrdom’s appeal to Christians merely historical, as Eliza Griswold reported in this 2007 TNR piece.

Glamour appeals to our desires, whatever they may be, and Jihadi glamour offers something for everyone: from historical importance to union with God, not to mention riches and beautiful women.

Postrel then quotes Egyptian cleric Hazem Sallah Abu Isma’il, indicating that the “beautiful women” in question are “black-eyed virgins” from a world conceptually above our own:

If one of these virgins were to descend to this world, her light would extinguish the light of the sun and the moon. That’s how beautiful she is.

Yet as Postrel comments, “glamour proves perishable”:

As Rushdie suggests, of course, glamour always leaves something out, in this case the literally gory details of the act .. Either aspirations change, entropy and boredom set in, or the audience learns too much, destroying the mystery and grace on which glamour’s beautiful illusion depends.

She concludes with a significant question and preliminary response:

How do we puncture the glamour of Jihadi terrorism? The first step is recognizing that such glamour exists.

That may seem like CVE 101, but the deeper our understanding of magic, imagination, image — and hence the power of glamour — the deeper our understanding of the deep problem that CVE presents will become.

**

Next we turn to Richard Fernandez, writing in A Bellyful of War, picking up the themes of war’s attraction, and the carnage its glamour omits from mention, and tying both to the notions of war as game and war as brutal reality:

William Tecumseh Sherman understood what many modern theorists have forgotten: war can be attractive to young men for as long as long as it remains a game. War in small doses is supremely thrilling, even glamorous. It is peace which can be routine and boring.

And so it goes until war stops being a game and the going gets really rough. “Its glory is all moonshine,” said Sherman. “It is only those who have never heard a shot, never heard the shriek and groans of the wounded and lacerated … that cry aloud for more blood, more vengeance, more desolation.” To Sherman a “bellyful of war” was ironically the psychological foundation of generational peace.

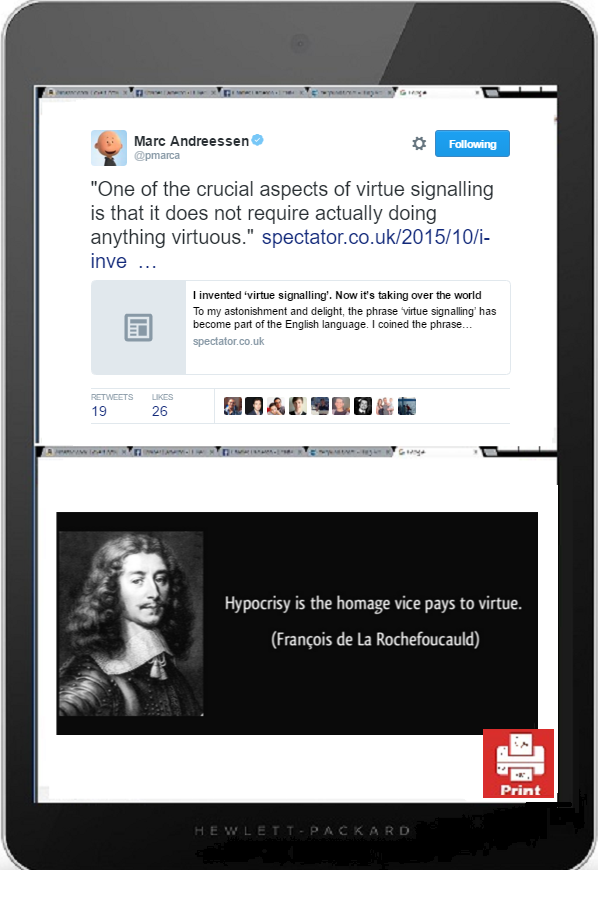

Not only is that last sentence a profound statement worthy of the contemplation of all who love peace – it is also far more subtly convincing than the old Strategic Air Command motto, Peace is Our Profession, which sounds more like one of Rochefoucauld’s tributes that vice pays to virtue than anything, and yet is presumably intended to convey the same insight.

**

Finally we have Plotinus, for whom – in a manner richly echoed by Shakespeare — life itself is a dream, a play, a sport, a game:

Murders, death in all its guises, the reduction and sacking of cities, all must be to us just such a spectacle as the changing scenes of a play; all is but the varied incident of a plot, costume on and off, acted grief and lament. For on earth, in all the succession of life, it is not the Soul within but the Shadow outside of the authentic man, that grieves and complains and acts out the plot on this world stage which men have dotted with stages of their own constructing. All this is the doing of man knowing no more than to live the lower and outer life, and never perceiving that, in his weeping and in his graver doings alike, he is but at play; to handle austere matters austerely is reserved for the thoughtful: the other kind of man is himself a futility. Those incapable of thinking gravely read gravity into frivolities which correspond to their own frivolous Nature. Anyone that joins in their trifling and so comes to look on life with their eyes must understand that by lending himself to such idleness he has laid aside his own character. If Socrates himself takes part in the trifling, he trifles in the outer Socrates.

Plotinus is correct, I would suggest, sub specie aeternitatis, just as is Sherman sub specie incarnationis — and it is the role of the artist to hold both visions, trivial and eternal, as Koestler suggests.

**

I am again grateful to David Foster for his ChicagoBoyz post The Romance of Terrorism and War which triggered this exploration and the one on Getting Deeper into Koestler which preceded it.