[ brief intro by Charles Cameron, then shorter version of Dr. Cath Styles‘ presentation of Sembl at the National Digital Forum in New Zealand, 20 November 2012 ]

.

Charles writes:

I’ve been working for almost twenty years on the development of a playable variant on Hermann Hesse‘s concept of the Glass Bead Game.

It’s an astonishing idea, the GBG — that one could build an architecture of the greatest human ideas across all disciplinary boundaries and media — music, religion, mathematics, the sciences, anthropology, art, psychology, film, theater, literature, history all included — and it has engaged thinkers as subtle as Christopher Alexander, the author of A Pattern Language [See here, p. 74]. Manfred Eigen, Nobel laureate in Chemistry and author of Laws of the Game [see here], and John Holland, the father of genetic algorithms [see here].

Here’s Hesse’s own description of the game as a virtual music of ideas:

All the insights, noble thoughts, and works of art that the human race has produced in its creative eras, all that subsequent periods of scholarly study have reduced to concepts and converted into intellectual values the Glass Bead Game player plays like the organist on an organ. And this organ has attained an almost unimaginable perfection; its manuals and pedals range over the entire intellectual cosmos; its stops are almost beyond number.

My own HipBone Games were an attempt to make a variant of the game that would be simple enough that you could play it on a napkin in a cafe, and has in fact been played online — and more recently, my friend Cath Styles has adapted it for museum play, and introduced the basic concept and our future hopes in a presentation at the National Digital Forum 2012, New Zealand — which you can see very nicely recorded in Mediasite format.

Do take a look — Cath makes a first-rate presentation, and I love the Mediasite tech used to capture it.

Since the slides are shown in a small window concurrently with Cath’s presentation, I’ve edited her presentation for Zenpundit readers, and reproduced many of her slides full-size with some of her commentary below.

**

Cath speaking:

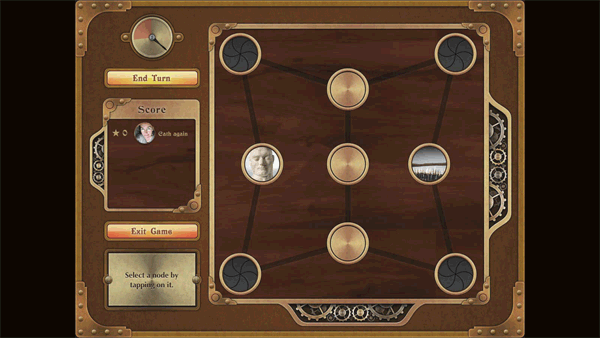

In its first form, Sembl is an iPad game, called The Museum Game, at the National Museum of Australia. We’ve just released it in beta as a program for visiting groups.

Cath then talks about feedback from children and adults about their experience of playing the game. Some kids homed in on the principle of resemblance, others emphasised the social side of the game. She talks, too, about their teacher, and her observations about the ways the game engaged her kids.

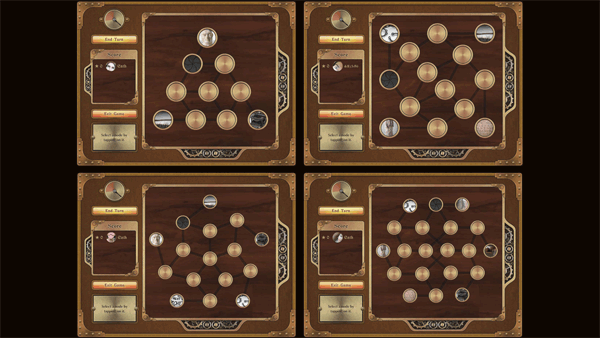

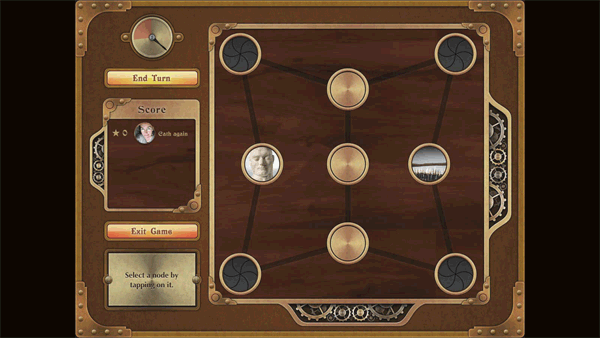

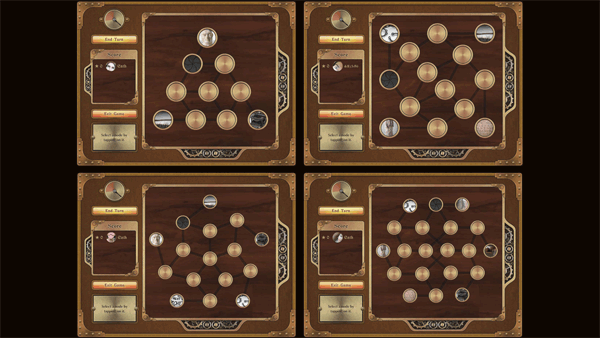

She then shows us various Sembl gameboards for iPad:

Cath speaks:

But The Museum Game is just one form of Sembl. The Museum Game is played in real time, on site, and players take photos of physical objects to create nodes on the board.

The next step is to make a web-based form, that you could play at your own pace, and from your own place. Then, Sembl becomes a game-based social learning network, which amplifies the personal value of the game – it becomes social networking with cognitive benefits.

But it’s the bigger picture – of humans as a community – that I most want to explore: Sembl as an engine of networked ideas, or linked data.

Charles notes: I’m skipping the educational part — and the bit about my own role in the game’s development, to get to the core of her presentation as I see it: the cognitive facilitation it provides

Cath again:

Another way of saying this is that the Game provides a structure and impetus for dialogue, between the museum and visitors, between visitors and things, among visitors and between things. And this is not dialogue in the sense of an everyday conversation. It’s deeper than that. It’s a mutual experience of looking both ways, simultaneously.

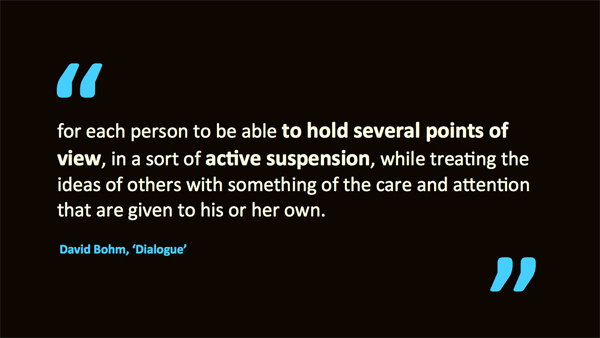

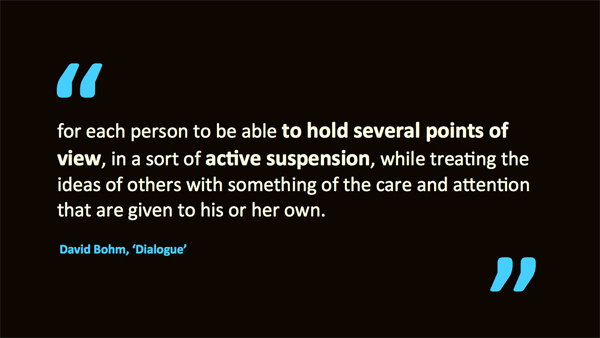

Cath next quotes David Bohm, the eminent quantum physicist:

Cath speaks:

For Bohm, dialogue means holding several points of view in active suspension. He regarded this kind of dialogue as critical in order to investigate the crises facing society. He saw it as a way to liberate creativity to find solutions.

Cath then drops in an important topic header:

Toward a game-based social learning network

Cath:

The concept of Sembl, in its deepest sense, is social learning – game-based social learning. In its first instantiation, it is game-based social learning in a museum and – if things turn out as I hope they will – from next year it will be playable at any other exhibiting venue that has the infrastructure and the will to host games – galleries, libraries, botanic gardens, zoos and so on.

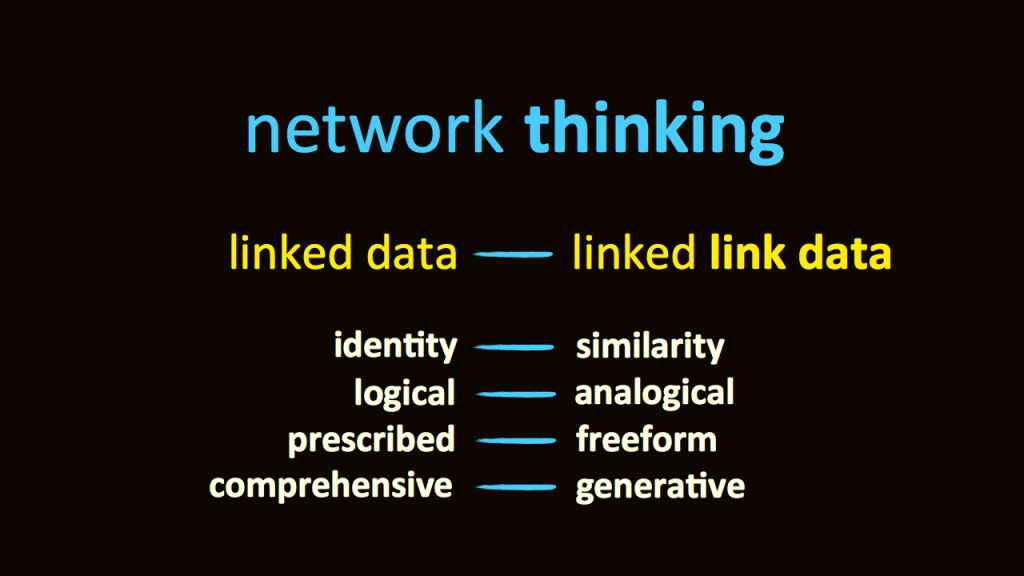

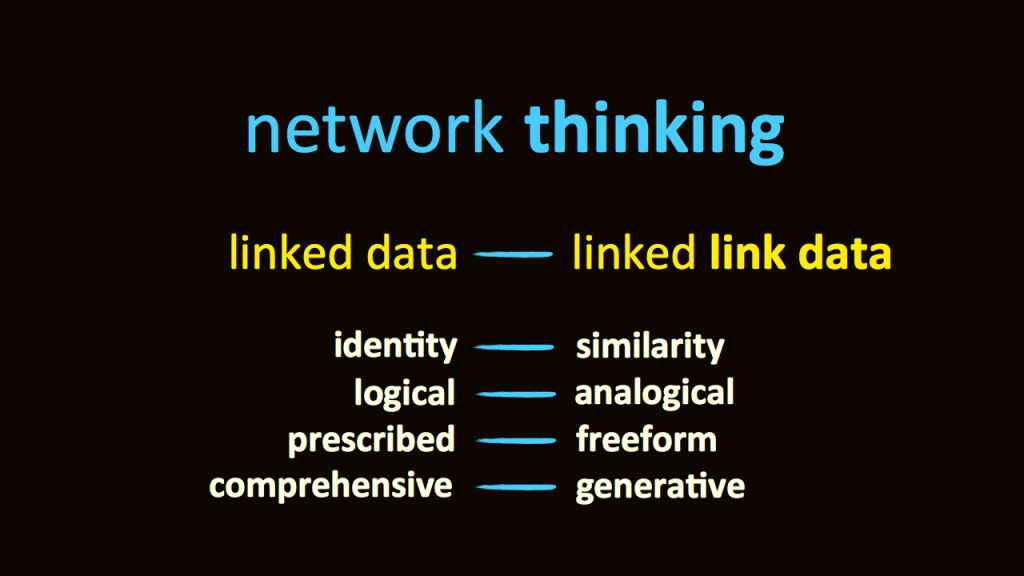

A web-based form of Sembl can generate linked data with a difference. It’s linked link data, and quite different to normal linked data.

- Instead of connections based on what a thing is – sculpture, or wooden, or red – Sembl generates connections based on a mutual resemblance between two things. Which, amazingly enough, is a great way of gaining a sense of what each thing is. And if your interest is to enable joyful journeying through cultural ideas, or serendipitous discovery, this approach just wins…

- Instead of compiling logical links, Sembl cultivates the analogical.

- Instead of building and deploying a structured, consistent set of relationships, Sembl revels in personal, imprecise, one-of-a-kind, free association, however crazy.

- Instead of attempting to create a comprehensive and stable map of language and culture, Sembl links are perpetually generative, celebrating the organic, dynamic quirks of cognitive and natural processes.

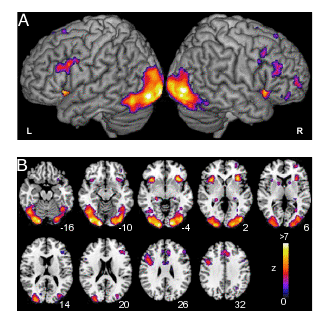

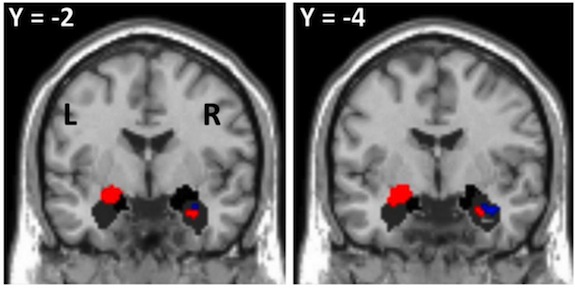

But the most important way that Sembl is distinct from other systems of network links is that those who generate the links learn network thinking. Which is a critical faculty in this complex time between times, as many smart people will tell you.

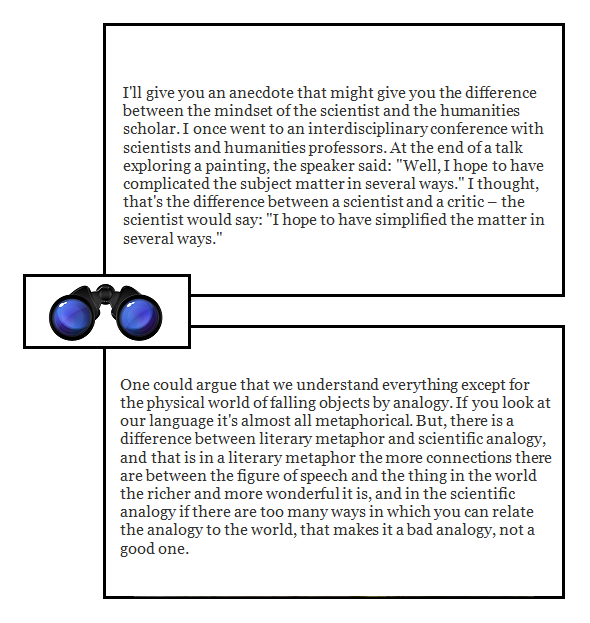

Poets have always known the virtues of analogy as a path to the truth.

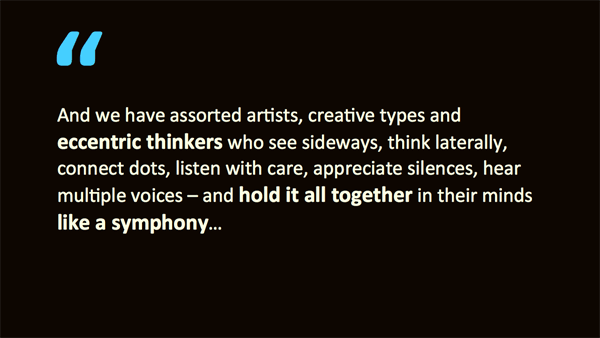

Sembl promotes dialogic, non-linear thinking, and new forms of coherence.

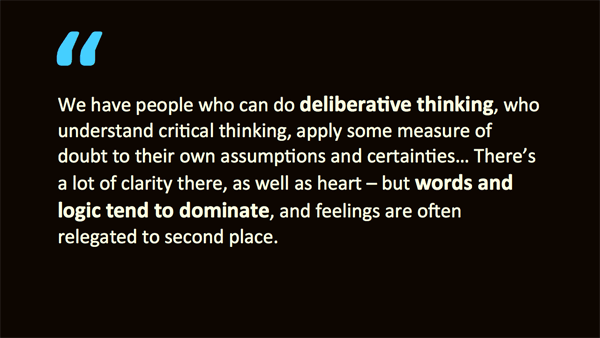

It’s distinct from deliberative thinking, which is rational and causal and logical and linear.

It’s another kind of thinking, which might be informed by rational thought, but its purpose is not singular.

You might say its purpose is to create – and cohabit – a state of grace, from which ideas simply emerge.

If playing Sembl gives us practice in polyphonic thinking, if it helps cultivate connectivity and our capacity to find solutions to local and global problems, it is good value. As Charles says, every move is a creative leap.

Cath concludes:

If you’re interested in working with us to supply content, develop strategy or raise capital, we’re keen to talk.

And I can’t tell you how much I’m anticipating being able to invite everyone to play.

**

Cath can be reached via Twitter at @cathstyles, and I’m at @hipbonegamer. The Sembl site is at Sembl.net.

Next up: what Sembl has to offer the IC.