A Clausewitzian on “Cohesion”

Thursday, December 30th, 2010Long time ZP readers are probably familiar with seydlitz89, a dedicated Clausewitzian and retired former military officer who comments here occasionally and blogs at Milpub regularly. I first read seydlitz89 at Dr. Chet Richards’ late, great, DNI site and seydlitz89 went on to participate in two extensive events at Chicago Boyz, the Clausewitz Roundtable and the Xenophon Roundtable and also had some of his more extensive writings featured on Clausewitz.com.

I would like to draw attention to one of those articles and seydlitz89’s focus on Clausewtz’s concept of “cohesion” and an implicit “theory of political development”. I am going to excerpt for my own purposes, but suggest that you read seydlitz89’s argument in full:

The Clausewitzian Concept of Cohesion as a Theory of Political Development

….The concept of cohesion comes up in various forms in On War and to lesser extent in Clausewitz’s other writings. These forms of the overall concept include:

- Cohesion as the moral (think tribalism, nationalism) and material (think constitution, institutions, shared views of how to define “civilization”) elements that make up the communal/social organizations of political communities, as exemplified in the three ideal types discussed below. Moral cohesion can be seen as the traditional communal values of a political community, what values and motivations guide people in their actions with family, friends and neighbours, whereas material cohesion are the modern cosmopolitan values associated with society or those social actions associated with institutions of various types. The two types exist is a certain state of constant stress and tension with modern values actually being destructive to the retention of traditional values (following Weber). Cohesion here is Clausewitz’s theory of politics which also includes the abstract concept of money. (Book VIII, Chapter 3B & the essay titled “Agitation”)

- Cohesion provides the process behind which the center of gravities of both participants in a conventional war are formed. Lack of a center of gravity would indicate the inability to win decisively, which would include the target of conventional militaries committed to unconventional/guerrilla warfare. (Book VI, Chapter 27, Book VIII, Chapter 4)

- Cohesion is the target of strategy in that tactical success is extended by strategic pursuit in order to expand the sphere of victory and bring about the disintegration of the enemy. Cohesion links the whole sequence of decisions (contingency) that allows the political purpose to be achieved through the means of the attained military goal, that is cohesion provides the chain of decisions/outcomes that unite political purpose with strategy and strategy with tactics, or vice versa. (Books II, IV, & Book VI Chapter 8)

- Cohesion acts within the balance of power among various states – especially in terms of interests – with an aggressor having to contend with all the other states having an interest in maintaining the status quo. This would include the tendency for Clausewitz of a potential hegemon to fail in its attempt to dominate other peer states. (Book VI Chapter 6)

- Cohesion can also be seen has having an influence in the varying states of balance, tension and movement through which all conflicts proceed. The cohesion (moral and material forces, willingness to take risks, soundness of the military aim in connection with the political purpose, etc) of each side being relatively equal while in balance, but increasing on one side during tension until a release of the tension (attack) and decreasing again during movement until balance is once again achieved or the conflict ends. (Book III, Chapter 18)

- At the most abstract level the concept of cohesion could be seen as providing the unifying concept which maintains the various elements (the remarkable trinity and the operating principles) of Clausewitz’s general theory as part of a whole, the fields of attraction and tension that provide the general theory with its dynamic quality. (Book I Chapter 1)

Thus cohesion can be seen as a very broad concept, but for my purpose I am using only the first point listed above.

and later:

….The third type of theory I wish to mention is what I refer to as Clausewitz’s theory of politics, or maybe more accurately, a theory of political development, which I see as inseparable from his concept of cohesion as I described in point one above in discussing the various forms of cohesion.

For our purposes here we are interested in Clausewitz’s concept of cohesion as it pertains to this first point, the physical and moral cohesive elements of political communities, how cohesion acts in effect as a sliding scale of ever increasing (or deceasing) concentration, integration and organization of a political community.

This is a very useful elucidation by seydlitz89, regardless if one favors Clausewitz or Sun Tzu or is altogether indifferent to military-strategic concerns and are more interested in broad questions of political philosophy and social policy.

Furthermore, I think Clausewitz’s speculations on cohesion were, like many of his systemic perceptions in On War, remarkably farsighted and intuitively rooted in a scientific reality that was unknown and untestable in his day. The conservative and eponymous scholar, Paul Johnson noted in his book Birth of the Modern that the 1820’s represented a time of great intellectual ferment when the arts, humanities and sciences were not yet compartmentalized, professionalized and estranged from one another. To paraphrase Johnson, it was still an era when a scientist like Faraday and an artist ( probably Harriet Jane Moore) could and did have a productive conversation about the properties of light in complete seriousness. As an intellectual, Clausewitz shared that zeitgeist.

In a military frame of reference, the concept of “cohesion” brings to mind the Greek-Macedonian Phalanx as a representative example

but the phenomena appears not merely in military tactics or in human social relations but throughout the animal kingdom. Howard Bloom, the popular science writer using a sociobiological perspective, used “Spartanism” and “Phalanx” as metaphors for documented behaviors of creatures as disparate as bacteria, baboons and hard shell Baptists. “Groups under threat, constrict” Bloom wrote in Global Brain and this characteristic of cohesion appears to apply even when the groups are not sentient. Network theorists and scientists can explain collective behavior in terms of “strong” and “weak” ties, nodes and hubs and resilience, including emergent behavior of systems are not even alive.

Cohesion is an aspect of the natural world.

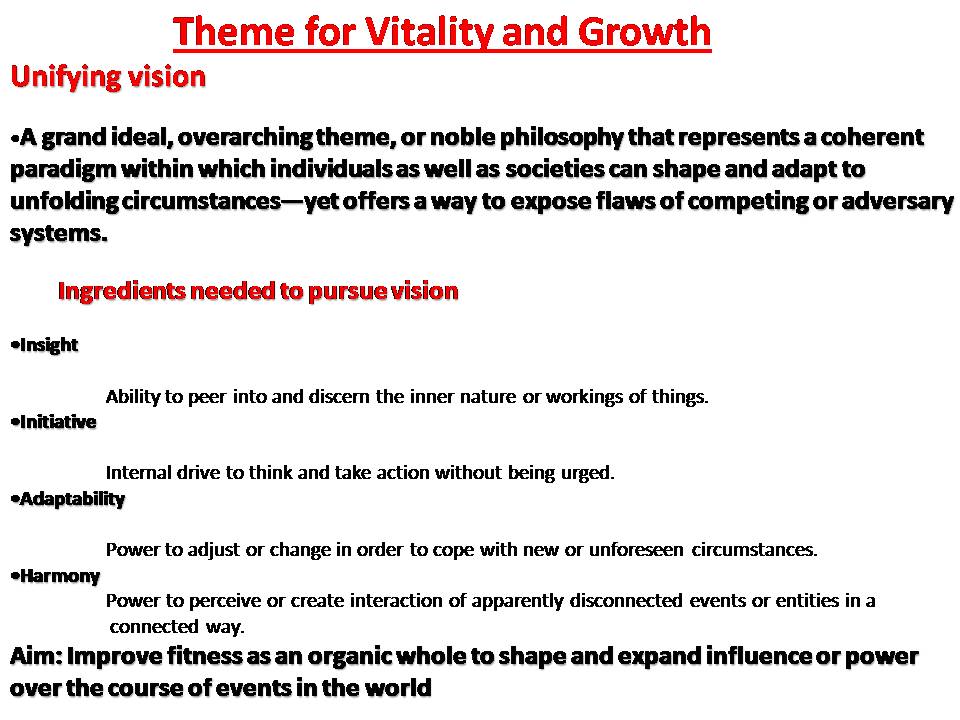

decision cycle faster than the opponent. But the importance of his writings to grand strategy is undeniable. His stress on the importance of forming organizations creative and efficient enough to “destroy and create” perceptions of the external environment, increase our own connectivity and degrade that of our opponents, and the importance of establishing a “pattern for vitality and growth” all point to aspects of strategic design that focus less on marshalling resources against a specific opponent than developing a basic strategic template that can remixed for various situations under a process of “plug and play.”

decision cycle faster than the opponent. But the importance of his writings to grand strategy is undeniable. His stress on the importance of forming organizations creative and efficient enough to “destroy and create” perceptions of the external environment, increase our own connectivity and degrade that of our opponents, and the importance of establishing a “pattern for vitality and growth” all point to aspects of strategic design that focus less on marshalling resources against a specific opponent than developing a basic strategic template that can remixed for various situations under a process of “plug and play.”