[by Mark Safranski, a.k.a. “zen“]

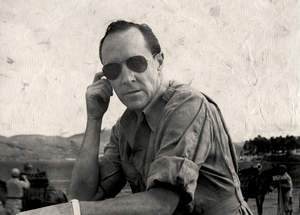

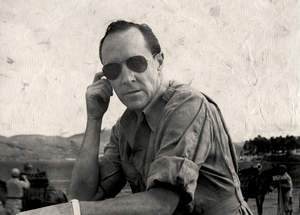

“China Hand” John Paton Davies

Our newest ZP team member, T. Greer of Scholar’s Stage blog has reposted two very thoughtful essays on the Chinese strategic tradition and its interpretation that can be found in modern Sinology. They are excellent and I encourage you to read them in full.

.

In his second post, T. Greer raises many questions regarding the state of Sinology, as well as topics for future investigation yet unexplored that would represent in equivalent fields, the fundamentals. Given that China represents not just a nation-state and a potential near-peer competitor of the U.S. but thousands of years of a great civilization, it is remarkable that the professional community of Western Sinologists is so small. The number of USG employees with the highest level of conversational fluency in Chinese who are neither native speakers nor children of immigrants would probably not fill a greyhound bus.

.

Why is the state of Sinology relatively parlous?

I think the poor state of Sinology is traceable primarily, albeit far from exclusively, to the Cold War for two reasons:

.

First, Mao’s

tumultuous,

totalitarian rule cut off access to Chinese sources and China to Western scholars for roughly a generation and a half. This in itself, coming on the heels of almost forty years of revolution, warlordism, foreign invasion and civil war, was enough to cripple the field. Without access to in-country experience, archival sources and foreign counterparts, an academic field begins to die. Furthermore, Mao’s tyrannical isolation of mainland China was far more severe than the limited access for Western scholars of Russian history and journalists imposed by the

Soviet Union.

Josef Stalin, in contrast to Mao, was partially a great Russian chauvinist and the Soviet dictator demanded certain aspects of Russian history, culture and the reigns of particular Tsars be celebrated alongside the Marxist pantheon . Mao’s feelings towards traditional Chinese culture were

much more hostile and ideologically extreme. Stalin’s worst abuses of Russian history in demolishing

a historic Tsarist cathedral for a never-built, gigantic Soviet labyrinthe pale next to the

mad vandalism of the

Cultural Revolution .

.

Secondly, the fate of “

the China hands” like

John Paton Davies and the “

Who Lost China” debate during McCarthyism rendered Sinology politically radioactive in America. It is true that many of the China hands like Davies combined a realistic strategic assessment of

Kuomintang/Chiang Kai-shek shortcomings with politically naive or wishful thinking about Mao and the Communists, but the field was dealt a blow from which it never recovered in American universities. Davies was not a Communist or even a leftist (though some China Hands were fellow travelers) but that nuance was lost on the public in a period that saw in swift succession

Alger Hiss, the Berlin blockade, the the Fall of China, the Soviet A-Bomb, Klaus Fuchs, the Rosenbergs and the

Korean War. It seemed at the time that the

Roosevelt administration had been infiltrated with Soviet spies and fellow travelers (largely because

it had been) and in that atmosphere of Red-baiting, Davies was subsequently scapegoated, smeared and fired. This McCarthyite political cloud over Sinology was curiously juxtaposed with the simultaneous robust funding of studies of the USSR, Russian culture and the training of Slavic linguists in the 1950’s to 1991 by the USG. For academics, going into Sinology could become a professional dead end and carried (at least in the early fifties) an odor of disloyalty.

.

There are certainly other and more contemporary reasons for American Sinology being more of an esoteric field than it deserves, to which someone else with expertise can address but all fields need to attract talent and funding and until Nixon’s “China opening”, American Sinologists struggled against the political current.