[ by Charles Cameron — a western koan makes it onto German TV? ]

.

What Hala Jaber calls a supermarket trolley in this tweet is not what this post is about — but it sure does connect trolley and terror!

**

Here’s the terror side of things, in a tweet from John Horgan:

The BBC halls it an “interactive courtroom drama interactive courtroom drama centred on a fictional act of terror” and notes:

The public was asked to judge whether a military pilot who downs a hijacked passenger jet due to be crashed into a football stadium is guilty of murder.

Viewers in Germany, Switzerland and Austria gave their verdict online or by phone. The programme was also aired in Slovakia and the Czech Republic.

The vast majority called for the pilot, Lars Koch, to be acquitted.

Here’s the setup:

In the fictional plot, militants from an al-Qaeda offshoot hijack a Lufthansa Airbus A320 with 164 people on board and aim to crash it into a stadium packed with 70,000 people during a football match between Germany and England.

“If I don’t shoot, tens of thousands will die,” German air force Major Lars Koch says as he flouts the orders of his superiors and takes aim at an engine of the plane.

The jet crashes into a field, killing everyone on board.

So, is the pilot guilty, or not guilty?

**

At the very least, he has our sympathy — but how does that play out in legal proceedings?

What’s so fascinating here is the pilot’s dilemma, which resembles nothing so much as a zen koan.

Except for the Trolley Problem:

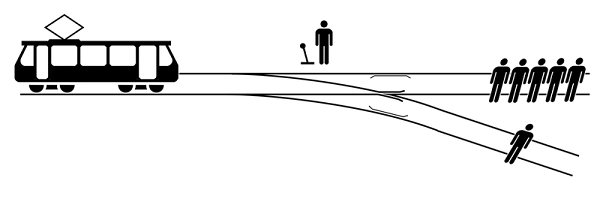

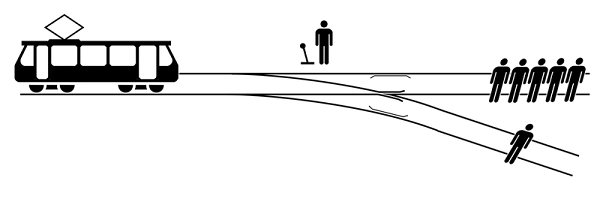

Image from Wikimedia by McGeddon under license CC-BY-SA-4.0

**

Substitute an Airbus for the trolley, 164 people for the lone individual on the trolley line, and 70,000 people for the cluster of five — and the pilot for the guy who can make a decision and switch the tracks.

There you have it: terror plot and trolley problem running in parallel.

To be honest, I think the full hour-plus movie is far more immersive, to use a term from game design, than the Trolley Problem stated verbally as a problem in logic — meaning that the viewer is in some sense projected, catapulted into the fighter-pilot’s hot seat — in his cockpit, facing a high speed, high risk emergency, and in court, on trial for murder.

It’s my guess that more people would vote for the deaths of 164 under this scenario than for the death of one in the case of the trolley — but that’s a guess.

**

The German film scenario — adapted from a play by Ferdinand von Schirach — is indeed a courtroom drama, a “case” in the sense of “case law”. And it’s suggestive that koans, too, are considered “cases” in a similar vein. Here, for instance, is a classic definition of koans :

Kung-an may be compared to the case records of the public law court. Kung, or “public”, is the single track followed by all sages and worthy men alike, the highest principle which serves as a road for the whole world. An, or “records”, are the orthodox writings which record what the sages and worthy men regard as principles [..]

This principle accords with the spiritual source, tallies with the mysterious meaning, destroys birth-and-death, and transcends the passions. It cannot be understood by logic; it cannot be transmitted in words; it cannot be explained in writing; it cannot be measured by reason. It is like a poisoned drum that kills all who hear it, or like a great fire that consumes all who come near it. [..]

The so-called venerable masters of Zen are the chief officials of the public law courts of the monastic community, as it were, and their collections of sayings are the case records of points that have been vigorously advocated.

**

Relevant texts:

John Daido Loori, Sitting with Koans

John Daido Loori, The True Dharma Eye