George F. Kennan: An American Life by John Lewis Gaddis

Former SECSTATE and grand old man of the American foreign policy establishment, Dr. Henry Kissinger, had an outstanding NYT review of the new biography of George Kennan, the father of Containment, by eminent diplomatic historian John Lewis Gaddis:

The Age of Kennan

….George Kennan’s thought suffused American foreign policy on both sides of the intellectual and ideological dividing lines for nearly half a century. Yet the highest position he ever held was ambassador to Moscow for five months in 1952 and to Yugoslavia for two years in the early 1960s. In Washington, he never rose above director of policy planning at the State Department, a position he occupied from 1947 to 1950. Yet his precepts helped shape both the foreign policy of the cold war as well as the arguments of its opponents after he renounced – early on – the application of his maxims.

A brilliant analyst of long-term trends and a singularly gifted prose stylist, Kennan, as a relatively junior Foreign Service  officer, served in the entourages of Secretaries of State George C. Marshall and Dean Acheson. His fluency in German and Russian, as well as his knowledge of those countries’ histories and literary traditions, combined with a commanding, if contradictory, personality. Kennan was austere yet could also be convivial, playing his guitar at embassy events; pious but given to love affairs (in the management of which he later instructed his son in writing); endlessly introspective and ultimately remote. He was, a critic once charged, “an impressionist, a poet, not an earthling.”

officer, served in the entourages of Secretaries of State George C. Marshall and Dean Acheson. His fluency in German and Russian, as well as his knowledge of those countries’ histories and literary traditions, combined with a commanding, if contradictory, personality. Kennan was austere yet could also be convivial, playing his guitar at embassy events; pious but given to love affairs (in the management of which he later instructed his son in writing); endlessly introspective and ultimately remote. He was, a critic once charged, “an impressionist, a poet, not an earthling.”

For all these qualities – and perhaps because of them – Kennan was never vouchsafed the opportunity actually to execute his sensitive and farsighted visions at the highest levels of government. And he blighted his career in government by a tendency to recoil from the implications of his own views. The debate in America between idealism and realism, which continues to this day, played itself out inside Kennan’s soul. Though he often expressed doubt about the ability of his fellow Americans to grasp the complexity of his perceptions, he also reflected in his own person a very American ambivalence about the nature and purpose of foreign policy.

John Lewis Gaddis was George Kennan’s official biographer, a relationship that can contradict and complicate the task of a historian to tell us “like it really was” by growing too close and protective of the subject. On the other hand, Kennan’s unusual longevity and undimmed intellectual brilliance into his tenth decade permitted Gaddis a kind of extensive engagement with Kennan that was exceedingly rare among biographers.

biographers.

I will be reading this book. Incidentally, Kennan’s own writings, notably his memoirs and his analysis of a totalitarian Soviet regime, Russia and the West under Lenin and Stalin are classics in the field of modern American diplomatic history, alongside books like Dean Acheson’s Present at the Creation. They are still very much worth the time to read.

The Gaddis biography will stir renewed interest and wistful nostalgia for Kennan at a time when the American elite’s capacity to construct or articulate persuasive grand strategies have become deeply suspect. Kennan himself would have shared the popular pessimism, having nursed it himself long before such a mood became fashionable.

ADDENDUM:

Cheryl Rofer weighs in on Kennan at Nuclear Diner

….Although the telegram and article did not deal explicitly with nuclear weapons, they were the basis for the strategy of containing, rather than rolling back, the Soviet Union and thus the arguments in the 1950s against attempting to eliminate the Soviet nuclear capability and in the 1960s against the same sort of move against China. Similar arguments continue today with regard to Iran.

Kissinger writes a sketch of Kennan himself and adds some of his own thoughts on diplomacy. The historical context of Kennan’s insights that he presents is worth contemplating in relation to today’s situation. How much of Cold War thinking can be carried into today’s thinking on international affairs, and how should it be slowly abandoned for ideas that fit this newer world better?

Addendum II.

Some fisking of Henry the K. by our friends the Meatballs:

Kissinger refers to Dean Acheson as “the greatest secretary of state of the postwar period.” False modesty or a ghostwriter? Gotta be one or the other, but we are leaning towards the former because no Kissinger Associates staffer would risk the repercussions from making a call like that.

Kissinger – the great Balance of Power practitioner – admired that Kennan (at least at times) shared his Metternich-influenced approach:

Stable orders require elements of both power and morality. In a world without equilibrium, the stronger will encounter no restraint, and the weak will find no means of vindication.

(…)

It requires constant recalibration; it is as much an artistic and philosophical as a political enterprise. It implies a willingness to manage nuance and to live with ambiguity. The practitioners of the art must learn to put the attainable in the service of the ultimate and accept the element of compromise inherent in the endeavor. Bismarck defined statesmanship as the art of the possible. Kennan, as a public servant, was exalted above most others for a penetrating analysis that treated each element of international order separately, yet his career was stymied by his periodic rebellion against the need for a reconciliation that could incorporate each element only imperfectly

officer, served in the entourages of Secretaries of State George C. Marshall and Dean Acheson. His fluency in German and Russian, as well as his knowledge of those countries’ histories and literary traditions, combined with a commanding, if contradictory, personality. Kennan was austere yet could also be convivial, playing his guitar at embassy events; pious but given to love affairs (in the management of which he later instructed his son in writing); endlessly introspective and ultimately remote. He was, a critic once charged, “an impressionist, a poet, not an earthling.”

officer, served in the entourages of Secretaries of State George C. Marshall and Dean Acheson. His fluency in German and Russian, as well as his knowledge of those countries’ histories and literary traditions, combined with a commanding, if contradictory, personality. Kennan was austere yet could also be convivial, playing his guitar at embassy events; pious but given to love affairs (in the management of which he later instructed his son in writing); endlessly introspective and ultimately remote. He was, a critic once charged, “an impressionist, a poet, not an earthling.”  biographers.

biographers.

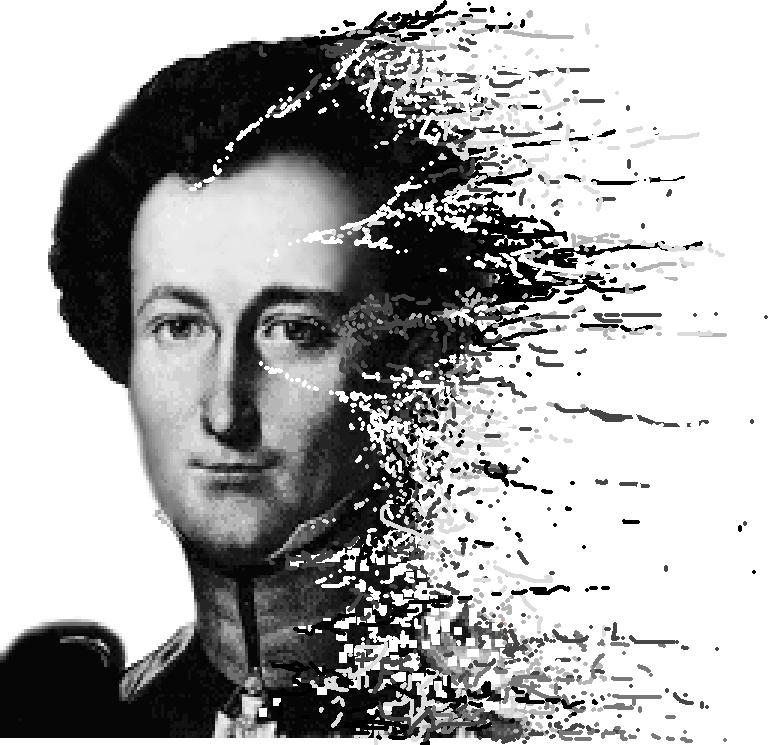

cholera, having finally risen to a military post his talents merited. He had been writing On War since 1816 and it was far from completed or refined to his satisfaction and it is highly unlikely, in my view, that Clausewitz would have consented to it’s publication in the condition in which he left it. His determined and intellectually formidible widow, Marie von Clausewitz, further shaped the manuscript of On War, guided by her intimate knowledge of her husband’s ideas and was likely the best editor Clausewitz could have posthumously had.

cholera, having finally risen to a military post his talents merited. He had been writing On War since 1816 and it was far from completed or refined to his satisfaction and it is highly unlikely, in my view, that Clausewitz would have consented to it’s publication in the condition in which he left it. His determined and intellectually formidible widow, Marie von Clausewitz, further shaped the manuscript of On War, guided by her intimate knowledge of her husband’s ideas and was likely the best editor Clausewitz could have posthumously had.