Of the importance of form in intelligence: I

Wednesday, October 3rd, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — form as pattern recognition, the form of suicide / martyrdom ops, a format for analysts, first in a series on form in intelligence, and maybe the beginnings of an eccentric thinking manual for analysts ]

.

Bear with me for a paragraph or two, while I try to sort something out.

Form is to content as algebra is to arithmetic: does that work for you? Form is one degree more abstract than content: how about that? I don’t think either of these expressions quite captures what I want to say about form and content, but they may help us think about form. Here’s a form:

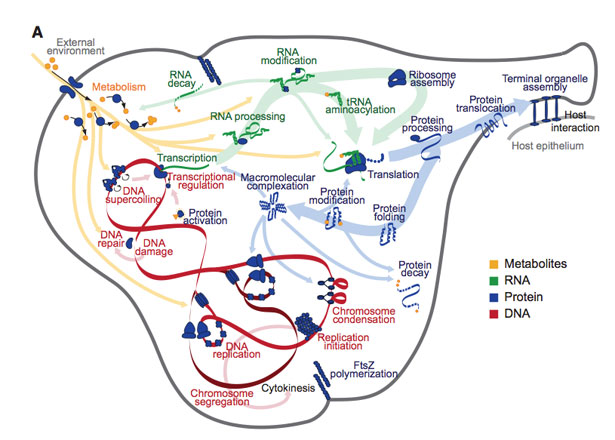

It’s pretty clearly a diagram of connections of some sort, but exactly what those connections are is unclear as long as the various boxes in the diagram remain empty.

I could fill it with the names of members of a hippie commune that practiced a flexxible approach to free love over a decade or two, from when the founder bought the farm (in the literal sense of real estate) to the point where the last surviving member bought the farm (metaphorically speaking — the farm in the sky).

Or with the names of elements in the human digestive and energetic system…

I mention the latter, because I came across this particular (empty) diagram on a blog post by a certain Jacques Chester about how people get fat, where it was preceded by the words:

A better diagram for bodyweight control will resemble a great big mess

I won’t tell you where I got the other idea from, if you want to know you’ll just have to fantasize, as I did.

**

At least in this case, form means pattern. The diagram above is a pattern, fill it with appropriate verbal or other content and you’ll give it meaning — which can then be disputed or accepted. But the form, the patterning, is somehow antecedent to any particular content.

Take the last words of each line of Shakespeare‘s Sonnet XCVII and you’ll get:

been, year, seen, everywhere, time, increase, prime, decease, me, fruit, thee, mute, cheer, near.

The rhyme scheme is pretty clear: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG.

That’s a form, and all of Shakespeare’s sonnets follow it. Petrarch‘s sonnets by contrast follow the rhyme scheme ABBA ABBA CDECDE.

**

In my practice of thinking, as a poet and as a practitioner of the open source analysis of scriptural sanctions for religious violence, I find the recognition of forms — pattern recognition — to be my central process.

I think what first really brought this home to me was the similarity of form between two reports of terrorist training activities — each in its own way illustrating the idea that the activity to be performed will begin quite naturally on earth, where training is required, but end quite supernaturally in paradise, where it isn’t:

That one’s pretty obvious, right? I mean, if you’ve seen the first instance you would be pretty likely to remember it if you ran across the second…

And what the form means is pretty clear too — martyrdom ops, suicide ops.

But what if you had a note-pad on your desk — or better, a game format on your computer — that gave you those two boxes, free of specific data, and any time you found a weird or anomalous data-point or image you could scribble it or drag-n-drop it into that form, give it a name for easy retrieval, and keep your eyes peeled for parallels, opposites, similars?

I call that format SPECS, by the way, because it allows you to see two similar ideas stereoscopically, so to speak, and thus gain an extra dimension — neat trick, eh?

What if collecting SPECS was part of your training as an analyst, and you practiced the form a few hundred times and kept 150 mind-blowing examples — as Shakespeare did with his ABAB CDCD EFEF GG sonnets?

**

Why, you’d be training yourself in pattern recognition — formal thinking — horizontal thinking — lateral thinking — analogy — thinking by leaps and bounds.

Inteligence happens in the Intelligence Community, and in the human population as well. I can’t speak to the ways in which animal and plant mimicry, or the artistry of birdsong, correspond to pattern recognition, although that would be a fascinating topic for another post.

What I can say is that analogical, horizontal, cross-disciplinary thinking is in its own away more powerful than logical, rational, vertical, silo-bound thinking.

**

In terms of Intelligence and intelligence, the strategies of linear / vertical thinking are like your fingers: it’s your skill at lateral / horizontal thinking that gives your mind an opposable thumb.